Abbie Hoffman is dead. So is Jerry Rubin. Tom Hayden, too. Their fellow protesters who disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in the last days of August 1968 are either gone or have become the very thing they once viewed with contempt: old.

But Abraham Yippie is very much alive at 73.

“It’s a long strange trip, from Daley/Nixon to Donald Trump,” said Abe Peck, now a professor emeritus at Northwestern’s Medill School, surveying the 50 years from today’s roiling political scene to when he was editor of the Chicago Seed underground newspaper, his pronouncements signed “Abraham Yippie.”

Mayor Richard J. Daley is dead. So are police Supt. James B. Conlisk and his deputy, James M. Rochford. The public officials and police officers who thought they were protecting their city from an onslaught by hippies, communists and radicals are gone or scattered.

But Officer Robert Angone is very much alive at 78.

“It was a big joke,” said Angone, then a tactical cop assigned to the Gresham District, now retired to Florida. “The SDS, Jerry Rubin’s group, Abbie Hoffman’s group — they were in a competition to get the attention they wanted. They wanted to get arrested the most, yell the loudest. We had all these goofy factions going on.”

The generation that didn’t trust anybody over 30 is now in their 70s and 80s. Their crew-cut contemporaries who didn’t trust those with long hair are the same. The divide they both gazed across with mutual incomprehension and disgust is very much with us, as the earthquake events of their era reach their golden anniversaries — traditionally the moment when human memory begins a steep decline and dry history picks up the story to carry it forward into eternity.

But before that happens, stand on Michigan Avenue, in front of what was then the Conrad Hilton Hotel, and feel your eyes sting from the tear gas. Cock your head and listen, hard, for the chant, faint at first, but returning to the roar it was in Chicago that final week of August 1968.

“The whole world is watching. The whole world is watching…”

Abe Peck was the Chicago point man for the Yippies, created early in 1968 for the sole purpose of upending the Democratic National Convention. They wanted to bring a “Festival of Life” to the city, to counterbalance what they called the “Convention of Death.”

The Yippies issued a manifesto: “Join us in Chicago in August for an international festival of youth music and theater….Come all you rebels, youth spirits, rock minstrels, truth seekers peacock freaks, poets, barricade jumpers, dancers, lovers and artists…. We are there! There are 500,000 of us dancing in the streets, throbbing with amplifiers and harmony. We are making love in the parks….”

Believe it or not, official Chicago was reluctant to host the Yippies, as well as the more serious protesters against the war in Vietnam.

“I negotiated with the city for six months,” said Peck. “The Yippie thing was built on media. To get continued media, the claims had to be more and more outrageous.”

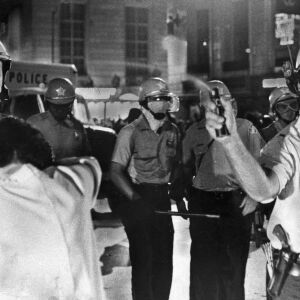

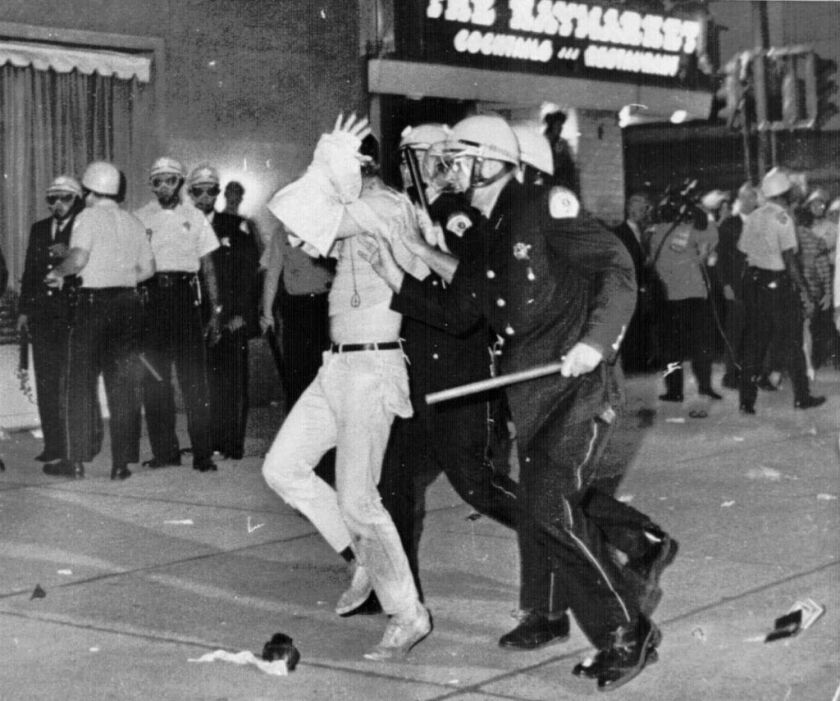

Those who remember need no reminder. They know what happened: youth gathered to vent its outrage. The police rioted. The Battle of Michigan Avenue. The raised nightsticks. Blood flowed in the streets.

Though at the distance of half a century, and listening to both sides, those certainties go out of focus.

“The cops were used to being cops, and here we were facing 10,000 people who didn’t give a f— about you,” said Angone. “I don’t think any police department in the world could have handled that. We were under siege.”

For those who don’t remember or who never knew, how to explain it? Where to begin? Lyndon Johnson became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963. The next November, he was elected in his own right, in part for making a vow:

“We are not about to send American boys nine or 10 thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves,” Johnson said, promising to keep America out of the growing conflict in Vietnam.

But send them he did. By 1968, America was mired in a bloody war. Young Americans poured into the streets. The Vietnam War protest movement widened the crack that the Civil Rights Movement had opened in the 1950s, between those who wanted to recast American society and those who wanted to preserve it.

In 1967, antiwar protesters marched on the Pentagon — Abe Peck took his company car to the Washington protest and kept going, marking his departure from the mainstream working world and toward Chicago.

The next year, 1968, America’s annus horribilis, which began with the Tet Offensive, a North Vietnamese drive that reminded Americans they were not winning the war and anyone claiming otherwise was deluded or lying. On March 31 Johnson announced he wouldn’t run for re-election. On April 4, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down in Memphis, igniting riots in cities around the country, including Chicago. That only four rioters were shot and killed here by police was considered “a model of coolness and compassion” compared to places like Detroit, where half of the 43 people killed in one 1967 riot were shot by the Detroit police or Michigan National Guard. In June, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, having just won the California primary. His last words were “And now on to Chicago….”

On to the Chicago of 1968. The John Hancock Building — “Big John,” as it was called — had just been built. The Sears Tower hadn’t. There were four daily newspapers. The city was the personal fiefdom of Mayor Richard J. Daley, in his 13th year in office. He controlled the Democratic Party, the city workers, and he wanted his city to shine in the gaze of the nation, having recently suffered through the bad publicity of the King riots and his notorious “shoot-to-kill” order.

Daley blamed the King riots on police restraint and ordered his brass: no more pussyfooting around.

“Daley For President” buttons were seen around City Hall, though the joke was that Daley wouldn’t want the demotion, preferring to dispatch one of his flunkies to Washington instead.

He had the power, and he decreed: There would be no hippies running riot in Chicago. There would be no permit to hold a Festival of Life. The parks would close at 11 p.m. The city of Chicago would hold firm in the face of an invasion of outsider rabble.

And in the eyes of blue-collar Chicagoans, particularly the police, the protesters were rabble, an unwashed, drugged, long-hair mob.

“Revulsion against this rabble came from the sweat of the people in this town, the sweat of their toil,” former Chicago cop Milt Brower told Frank Kusch in his essential book “Battleground Chicago: The Police and the 1968 Democratic National Convention.” “They were hard-working people who would not put up with the things that were beginning to happen.”

Or, as Bob Angone puts it today: “There was that hawk-and-dove sh– going on in the country.”

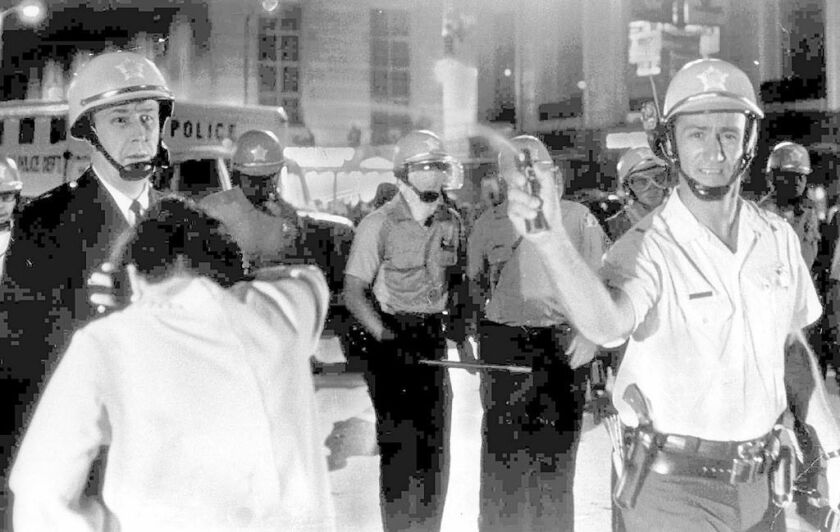

Chicago police attitudes were such that, several days before the convention began, with the National Guard had already been called up, police Supt. Conlisk felt the need to issue the following reminder to his officers:

“The eyes of the nation and the world will be on our city and our department. We must continue to be constantly mindful of the welfare of others, never act officiously and never permit personal feelings, prejudices or animosities to influence our decisions or our actions. To a substantial degree, it will be by our actions that the rest of the world will judge Chicago and in some degree our nation itself.”

That judgment rankled. Then as now, police despised the news media.

“I think it’s kind of a universal thing, don’t you?” said Angone.

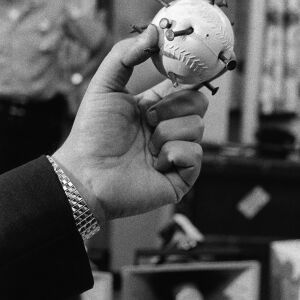

This, despite the fact that press was still often content to pass along the official city line. The Tribune — the Fox News of its day — was run by the acolytes of its powerful former boss, the red-baiting Col. Robert R. McCormick. “The demonstrators must be working for communist North Vietnam,” the Tribune had editorialized after the riots following King’s assassination. Jack Mabley, a columnist at the Chicago American, credulously passed along every rumor and supposed plot. “Natural gas lines coming into the city may be dynamited and set afire,” he panted. “Militants have said they will put agents into hotel or restaurant kitchens where food is prepared for delegates and puts drug or poison in the food…”

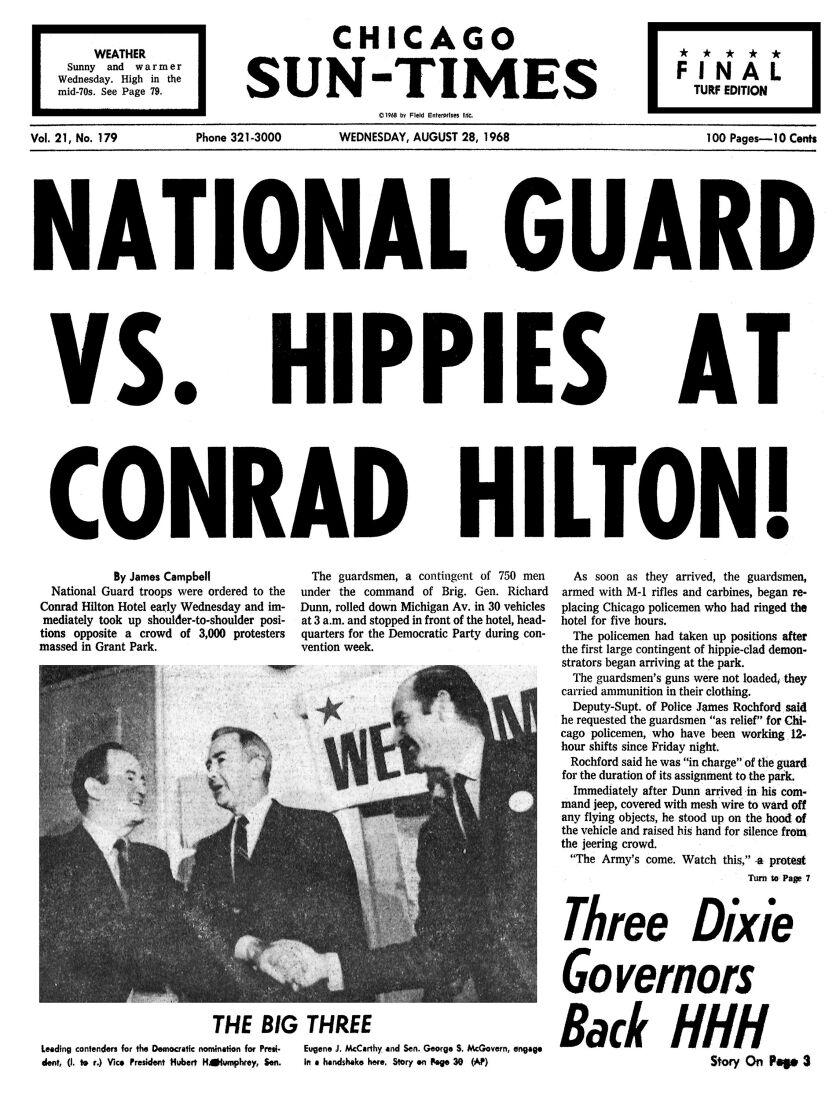

“Daley is a brilliant chief executive whose efficiency is matched by his sense of responsibility” the Chicago Sun-Times reported the day before the convention opened, citing “his deep and systematic morality” and invoking Solon the lawgiver.

The convention was held at the old International Amphitheatre, five miles south of the Loop at 42nd and Halsted, a brick barn built in the early 1930s to host livestock shows.

Just getting there was a challenge. Taxi drivers went on strike as the convention began. The building was crawling with plainclothes security working for Daley, intent on keeping order in the hall, preventing any unapproved candidate from gaining momentum. One of these guards stopped a New York delegate from entering because he was carrying a copy of the dreaded New York Times. Barred from demonstrating near the convention, supporters of antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy held their rally in Philadelphia.

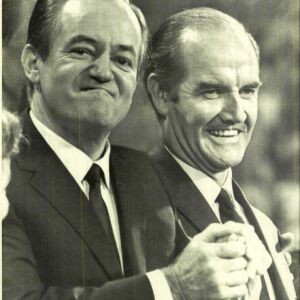

Had there been no protest, the convention’s doings hardly would have merited interest: The fix was in. Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, had inherited his support. And though the majority of Democrats supported peace candidates McCarthy and George McGovern, bosses like Daley held sway. Humphrey was always going to be the winner.

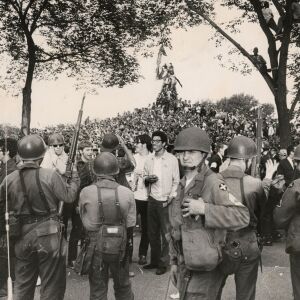

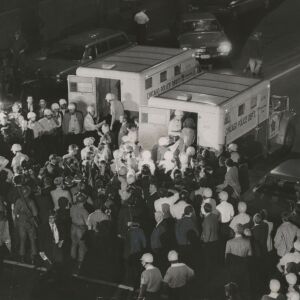

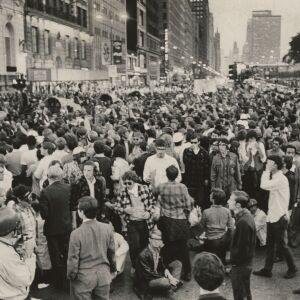

Fearful of protest undermining his show, Daley had so completely blocked off the Amphitheatre that protesters couldn’t get near it. Still, the protest turnout was surprisingly small. On the eve of the convention, there were 12,000 Chicago police officers on full alert, working 12 hour-shifts, nearly 6,000 mobilized Illinois National Guard, 5,000 U.S. Army combat troops, fully armed, with flamethrowers and bazookas, arrayed against 2,000 to 5,000 actual protesters from out of town, plus thousands of curious local youth wandering over to check out the scene.

The first protest was small-scale. On Aug. 23, a Friday, a black-and-white pig the Yippies dubbed “Pigasus” was led out of a truck at what was then the Civic Center, now the Daley Center. The police instantly arrested seven Yippies, including Jerry Rubin and the folk singer Phil Ochs, who had bought the swine, which was taken into custody “as evidence.”

Saturday night, Lincoln Park was cleared almost without incident. Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, who had been leading a group of 100 or so in his “omm” chant, led them ceremoniously out of the park at 11 p.m., which the police announced through bullhorns was closed, sweeping off the few stragglers.

Each night got progressively worse as tempers frayed and violence escalated. Argone said few people considered the exhaustion of the police.

“I’ve never heard anybody ever bring up, except coppers,” he said. “But the fatigue, the thirst. you can’t go 10 feet now without seeing somebody with a water bottle. That wasn’t the case then then.”

He said cops would show up for their shifts with five or six Tootsie Rolls crammed in their pockets.

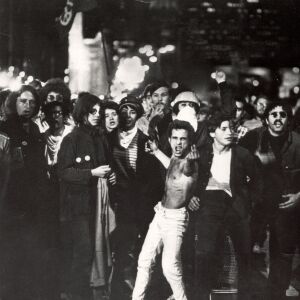

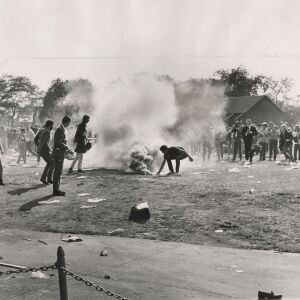

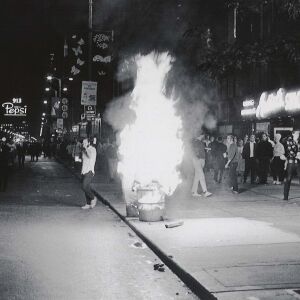

Sunday, protest leaders had been advising people to “test the curfew.” There were several thousand people in Lincoln Park, around bonfires, beating drums, chanting “Revolt! Revolt!”

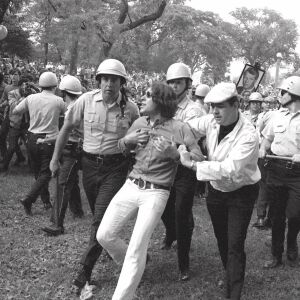

The police formed a skirmish line and cleared the park, ending up on Stockton Drive, with about 200 cops facing 2,000 or so protesters. Then the crowd reacted, and the police broke ranks.

In “Chicago ’68,” history professor David Farber describes the scene: “Some police beat people bloody. Some demonstrators fought back. They were beaten to the ground and then beaten some more, one of the policemen involved said, ‘No attention was paid to the amount of violence used’ on these resisters. People chanted that ‘the streets belong to the people.’ And they refused to clear the streets. Many wanted the confrontation.

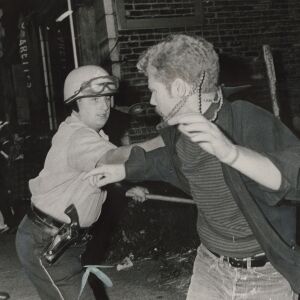

“Photographers who attempted to take pictures of the police in action, were clubbed in turn — ‘Get the bastard with the camera’ — and their cameras smashed. A reporter for Newsweek, when told to get out of the street, flashed his credentials. ‘Newsweek f—–s,’ the cop replied and then clubbed him on the head, neck, back and upper thigh….Policemen chased people for blocks in order to club them to the ground. The conflict spread to the side streets. Many of the policemen had removed their nameplates and badges.”

By Monday, the first day of the convention, the city’s collective mood already was tense. As the putative nominee, Humphrey arrived at the Hilton, and someone set off a stink bomb in the lobby.

That afternoon, there was a famous melee around the state of Gen. John Logan in Grant Park across from the Hilton. A young man climbed it. The police hauled him down and arrested him, breaking his arm in the process.

“Monday night,” Norman Mailer wrote, “the city was washed with the air of battle.”

The police would clash with protesters, which drew reporters’ attention, which the police felt was unfair.

The press complained to Daley about the media being singled out for attack, and Daley said, “In the heat of emotion and riot, some policemen may have over-reacted.”

“Most of the time, they don’t see the provocation,” said Angone. “They just see the goofy policeman going off half-cocked with his club in the air. I’m not saying everyone is a f—–g angel. It was a f—–g brawl. You hit me. I hit you.”

But the police also attacked passersby, random Chicagoans watching the action or caught up in it, blaming them for being there.

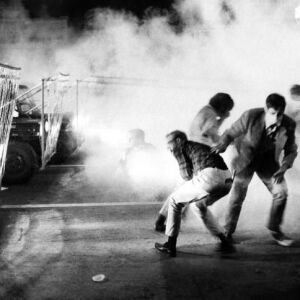

The park clearing began at 12:30 a.m. Tuesday. But that only pushed angry protesters, and the cops chasing them, into the streets.

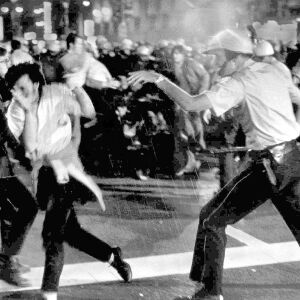

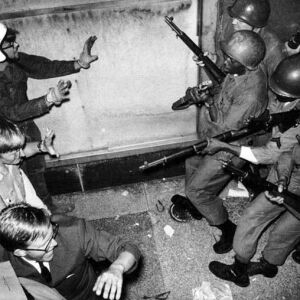

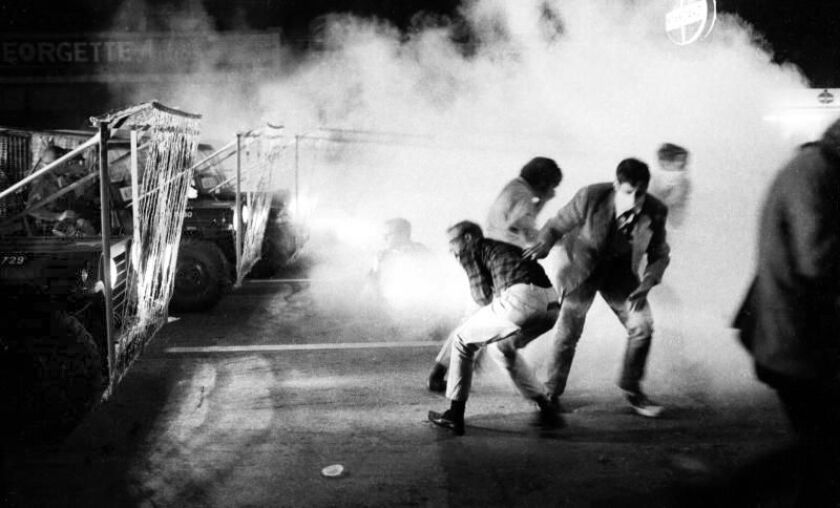

On Wednesday came the moment everyone thinks of when they think of the convention, “The Battle of Michigan Avenue,” a 17-minute melee in front of the Conrad Hilton, broadcast on TV, interspersed with the action on the floor of the convention.

Several thousand protesters attempted to march on the Hilton. The police were determined to stop them.

“The police gathered in groups,” New York columnist Jimmy Breslin wrote. “and then ran into the kids and swung their clubs, cops in blue helmets and short-sleeve blue shirts. Cops with bare arms, swinging in the television lights while they went for the head with their clubs, or for any place below the belt they could reach. Chicago cops who had been misdirected all day and now were completely without supervision. They were running to young kid and beating them…”

“Some of the youths fled into the hotel,” the Sun-Times’ Hugh Hough wrote. “and convention visitors and other guests looked on in amazement as club-wielding police pursued and subdued the long-haired youngsters.”

Hotel guests threw toilet paper — and glass ashtrays — down at the police. Police pushed protesters through plate-glass windows, then pursued them inside and beat them as they sprawled on the broken glass. All told, 100 protesters were treated for injuries — plus 119 cops. About 600 protesters were arrested.

These images seared themselves in the national mindset.

Or did they?

No question, when the convention ended, the city’s reputation that Daley had so vigorously sought to preserve lay in ruins.

“The Democratic Party woke up today with the worst hangover in a century,” wrote David Broder in the Washington Post, saying Humphrey resembled “the general of a defeated and mutinous army.”

Richard Nixon ended up winning the general election, barely, squeaking past Humphrey, a victory that stunned those who saw the Republican standard-bearer as a red-baiting villain from the Red Scare ’50s and was blamed squarely on the convention.

“It stained the reputation of Chicago for a long time,” said Peck. “Until Michael Jordan, the associations were: Al Capone and the Democratic National Convention.”

The long-term effect on the nation is not so clear. Even though the Walker Report’s famous conclusion of a “police riot” reverberated, it was rejected by the police and a wide swath of America.

A major poll two months after the convention found that more people thought the police had used too little force than too much, 25 to 19 percent.

Seeing the handling protesters got did not popularize the antiwar movement, and the war in Vietnam would go on for seven more years.

“People disliked the protesters more than they disliked the war,” said Peck.

Daley, who a few years earlier had been on the cover of Time as a model mayor, was demonized. He did worse at the polls at the next mayoral election, carrying only 48 of the city’s 50 wards — in 1967, he won them all.

He would not be seated at the 1972 Democratic National Convention, which veered hard left and embraced dove George McGovern on its rendezvous with electoral disaster.

Since Abraham Lincoln had been nominated here in 1860, centrally located Chicago had hosted 14 Republican conventions and nine Democratic conventions — four in the previous decade. But 28 years would pass before either political party again would take a chance on the city.

For years, the convention was seen as vastly significant.

“In its psychic impact, and its long-term political consequences, it eclipsed any other such convention in American history,” wrote political commentator Haynes Johnson. “Destroying faith in politicians, in the political system, in the country and in its institutions. No one who was there, or who watched it on television, could escape the memory of what took place before their eyes.”

The police, while insisting they did nothing wrong or had valid reasons if they did, said that they learned from their non-errors. Subsequent protests were not as violently squelched.

“That NATO summit was probably the Chicago Police Department’s finest hour,” said Angone. “I don’t know if Garry McCarthy was responsible for that, but I have never seen crowd control like that, with hardly any violence. He was even sharp enough to change the skirmish lines, to replace the coppers on the front line every two hours so the baiters couldn’t get to you.”

And now that surreal farce has returned to the nation’s politics, the convention’s impact seems less apparent.

“Trump is the ultimate Yippie,” said Peck. “All spectacle.”

Then again, maybe confused, unresolved spectacle and conflict, to a greater or lesser degree, is the nature of the democratic beast.

“The longer I live, the more I realize how many people don’t pay attention to anything,” said Peck, who thinks the effect of the 1968 convention on the public is less than the participants might fancy. “The great divide continues Despite all the change, despite Chutes and Ladders, progress and regress, there’s a fundamental divide in how we decide where to go or whether we want to go anywhere at all. Obama liked to quote Martin Luther King about how the arc of history bends toward justice. I hope it does. But it has a lot of twists in it.”

Contributing: Robert Shea