On a summer day in the early 1960s, Miriam Balanoff took her three children along for a civil rights march down State Street.

From the sidewalk, one of her classmates from the University of Chicago Law School pointed her out.

“Miriam, I’m surprised at you!” the onlooker yelled.

“No, I’m surprised at you!” Mrs. Balanoff replied. “You should join us.”

The exchange stuck with her son Clem Balanoff Jr. –– just one instance of the socially engaged attitude she tried to instill in her kids — and inspire in others.

“She was marching for civil rights before it was fashionable. She was arguing for marriage equality before people even understood what that meant,” her son said. “She told people the truth, even if it wasn’t what they wanted to hear.”

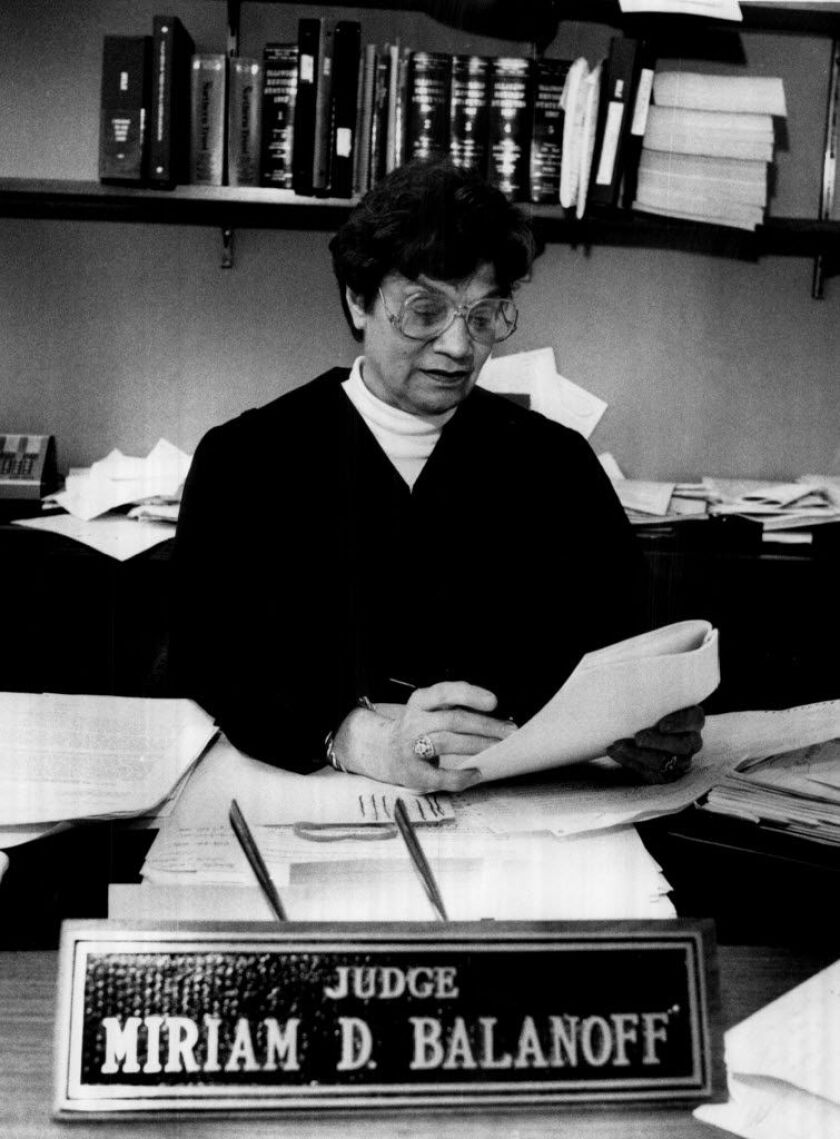

Mrs. Balanoff would later became a state representative, Cook County judge and a mainstay in progressive causes across Chicago. A matriarch of the family name that has become synonymous with Illinois union organizations and grass-roots politics, she died last September at age 91 after several years battling dementia, her family announced this past week.

Born Miriam Dweck on March 4, 1926, to Jewish Syrian immigrants in Brooklyn, she grew up in foster homes, a harsh upbringing that shaped her views.

“She saw the suffering that many people had to endure. And she wanted to make things right,” her son said.

She went to Hunter Junior College in Manhattan and graduated as valedictorian. Her first job out of school was at Penguin Publishing, and her family says she loved the perks: “All the free books I could read!” she would say.

Miriam then moved to Ohio to organize a union at a light bulb factory, before arriving at the University of Chicago where in 1952 she met and married Clem Balanoff, a steel-working union activist and political strategist — with a kindred spirit for social justice.

She joined the second generation of a Chicago family with activism in its blood. Bulgarian patriarch James Balanoff, her father-in-law, settled in the South Chicago neighborhood in the early 1920s, and descendants since then “have been stirring folks up and ticking folks off and catching hell in return,” as the Chicago Sun-Times’ Tom McNamee wrote in a June 1989 feature on the family.

“They fought for unions when unions were reviled. They fought for racial desegregation in the schools when other South Side whites abhorred desegregation. They backed Harold Washington for mayor when few whites — especially in the old ethnic neighborhoods — dared,” McNamee wrote, later describing Mrs. Balanoff as “tiny and talkative and possessed of enough energy to fill a room.”

As she and Clem raised three children, Mrs. Balanoff earned an undergraduate degree at the University of Chicago, and she stayed on a full scholarship to earn a law degree there in 1963 — one of three women in her graduating class.

An advocate for women’s, civil, LGBTQ and workers’ rights, she opened a storefront private practice doing neighborhood legal work, and she also taught a class on women and the law at area colleges.

“She did things in a time when women were expected to be home in the kitchen,” her son said.

Her family pushed her to run when their local Illinois House seat opened up in 1978, and she would serve two terms with stunning victories over members of the powerful political organization of Ed Vrdolyak — a classmate at the U. of C. and a “lifelong nemesis,” her son said.

In the statehouse, Mrs. Balanoff proposed bills to protect workers affected by plant closings, and she fought to remove sales taxes on foods and medicines.

She would make failed bids against Vrdolyak for his 10th Ward aldermanic seat in 1983 and then his Democratic ward committeeman seat in 1984, during a decades-long rivalry with the man she dubbed the “Darth Vader of Illinois politics.”

Mrs. Balanoff was an early backer of Mayor Washington, and with his support she was elected in 1986 as a Cook County Circuit Court judge, serving 14 years on the bench mostly in pro se court, according to Clem Jr., whom she later helped elect to the state legislature.

When she wasn’t advancing her causes, Mrs. Balanoff loved traveling, she enjoyed theater, and she always had time for a game of Casino, her son said.

“The Balanoff family throughout the years has made enormous contributions to the struggle for economic and social justice,” Chicago Federation of Labor President Bob Reiter said. “The Honorable Miriam Balanoff exemplified this legacy throughout her career, serving the people of Chicago and Illinois. She’ll live on through her family as they continue to fight for fairness and justice in our city.”

In addition to Clem Jr., Mrs. Balanoff is survived by her other children Jane and Robert; brother-in-law Ted Balanoff and sister-in-law Betty Balanoff; nine grandchildren; a great-grandchild; and many nieces and nephews.

A memorial service is scheduled for 11 a.m. on May 19th at Workers United Union Hall, 333 S. Ashland.