Someone suggested this would be a good time to remind everyone — but Ald. Anthony Beale (9th) in particular — about the story of Harold Washington, Perry Hutchinson and the wheelchair.

It’s the story of a Chicago alderman who crossed a popular mayor and paid dearly for it.

The suggestion came from a former member of the late mayor’s City Council coalition, a shy fellow who would rather leave his own name out of it.

Hutchinson was alderman of the 9th Ward on the city’s far South Side, same as Beale.

He was elected on Washington’s coattails in the historic election of 1983 that gave the city its first black mayor.

Hutchinson, as you will see, wasn’t much of a politician, but he was smart enough to back Washington after the incumbent alderman, Robert Shaw, made the miscalculation of supporting the sitting mayor, Jane Byrne, for re-election.

Electing Washington became a crusade in Chicago’s African American community, and Hutchinson rode the mayoral candidate’s wave of popularity into office.

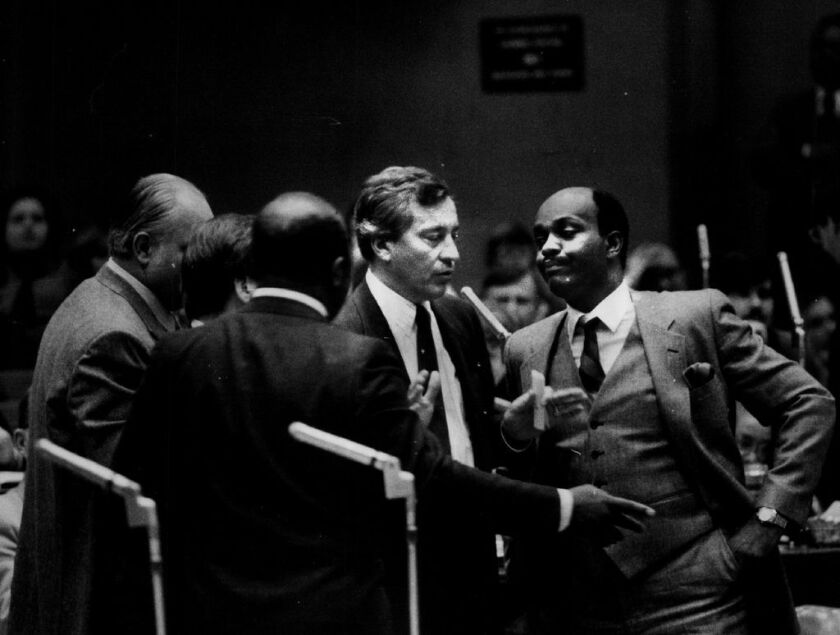

That made Hutchinson part of a group of 21 aldermen holding the short end of the stick during Washington’s frustrating first three years as mayor when they were thwarted at most every turn by the majority of 29 aldermen led by aldermen Edward R. Vrdolyak and Edward M. Burke — the period in Chicago political history known as Council Wars.

The balance of power changed in the spring of 1986 when special elections swung enough City Council seats in Washington’s favor that he could break tie votes.

Washington immediately moved to exert his authority, starting with some of his long-stalled appointees to city boards and commissions.

On May 30, 1986, the City Council met on a Friday with Washington’s forces planning to advance the appointment of architect Walter Netsch, husband of then-state Sen. Dawn Clark Netsch, to a seat on the Chicago Park District Board. It was a critical vote because Parks Supt. Ed Kelly was a Washington nemesis.

But when it came time to vote, two of Washington’s allies could not be found. In the parlance of legislative bodies, they “took a walk,” supposedly in a snit over not being consulted.

“I looked around and they were gone!” Ald. Timothy Evans, Washington’s floor leader, said at the time.

Word of the apparent betrayal spread fast. The missing aldermen came in for especially harsh criticism the next day at Operation PUSH’s weekly meeting and radio broadcast.

After three years of fighting to give Washington the control normally accorded a Chicago mayor, African Americans were not about to allow two of their own aldermen to muck up his agenda.

By the time I caught up with Hutchinson the next day on Sunday, he was in the cardiac surveillance unit at Michael Reese Hospital, explaining he’d checked himself in to deal with the stress from all the threatening phone calls he was receiving.

Hutchinson tried to chalk it all up to a misunderstanding, saying he had left the Council meeting early to go to the doctor, not realizing there was a plan to vote on the Netsch appointment.

“This has just really upset me,” he told me. “My blood pressure just went up getting all these phone calls. I’m supporting Harold Washington on all his appointments. I’m really sorry this happened.”

And that’s how it came to be just five days later that a haggard-looking Hutchinson was whisked by ambulance to City Hall and taken by wheelchair to the Council chambers.

“I’m going to do my thing for the mayor,” Hutchinson announced during his dramatic entrance, just before voting with Washington for a Council reorganization plan that dumped Vrdolyak and stripped Burke of his budget powers.

Vrdolyak accused Washington of an illegal power grab.

“No, it’s not a power grab. It’s an adjustment of power,” Washington said.

Hutchinson was wheeled back to the ambulance and back to the hospital, the rest of his obscure one term in office interrupted only by two federal convictions. He died in prison at age 48.

This is where I’m supposed to draw the comparison to Beale, who thought he was an ally of Lightfoot and even took the liberty of speaking for her, only now to find himself in her doghouse with no spot in her City Council lineup.

Beale doubled down on his earlier mistake Monday by dismissing Lightfoot’s executive order limiting aldermanic prerogative as “not worth the paper it’s printed on.”

But is the price for crossing Lightfoot as steep as the price for crossing Washington, and can a 20-year Council veteran like Beale be brought into line as easily as the sadly overmatched Hutchinson?

African American voters had Harold Washington’s back. So far, it hasn’t been proven they have Lightfoot’s to the same extent.

If you were Beale, though, you’d want to watch out for that power adjustment.