The controversy over where to put a Chicago casino illustrates a common belief — that the best way to bridge the city’s wealth gap is to create more jobs in outlying neighborhoods, not downtown.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker thinks a casino should go in a community that has been “left out, left behind.”

On election night, a TV commentator said the new mayor’s focus should be on community employment.

Awhile back, an industrial group argued that Chicago needs more “living-wage” jobs — presumably in fields like manufacturing — not office jobs requiring “advanced degrees.”

These views might sound reasonable. But they’re wrong.

The most effective way to boost struggling neighborhoods is to help those who live in them get jobs downtown.

That’s where most new jobs in Chicago are going to be — and it’s not just people with MBAs or law degrees who will get them.

The charts below show why this is so.

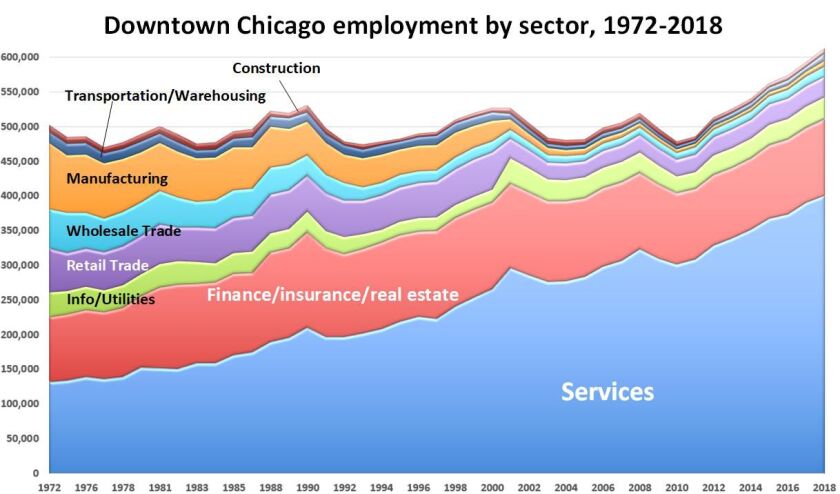

The first illustrates where Chicago’s jobs have been since 1972, the numbers taken from the Illinois Department of Employment Security’s yearly “Where Workers Work” reports.

The state agency has tweaked its methodology over the years, so any comparisons over long intervals are approximations, but the conclusions are sound.

The number of jobs in Chicago hasn’t changed much, even though the city’s population has fallen by more than 650,000 since 1970. Jobs now number around 1.2 million — about the same as in the mid-1970s.

What’s different, though, is the type of jobs and where they are.

In 1972, about 60% of jobs were in the neighborhoods and 40% downtown — defined as the Loop plus portions of the Near North Side, Near West Side and Near South Side.

Today, more than half of the city’s jobs are downtown — that’s about 613,000 workers, which is the highest in modern recordkeeping. Downtown employment growth has been particularly strong since 2010, generating nearly 134,000 jobs.

For some context, the number of jobs in the rest of the city has fallen by close to 30% since 1972.

Why? In 1972, Chicago was a major industrial center, with 435,000 jobs in manufacturing, many in factories in outlying parts of the city. Today, only 63,000 manufacturing jobs remain. And other once-dominant job categories — like wholesale and retail trade — also have dwindled.

Deindustrialization obviously isn’t confined just to Chicago — it’s played out across the United States and much of the developed world. And as much as people might wish otherwise, those jobs aren’t coming back.

What’s grown has been employment in service industries, from health care to technology. In 1972, services employment accounted for 277,000 Chicago jobs. As of 2018, there were 727,000 jobs in services — more than 60% of all the jobs in the city, the majority of them downtown.

And, as the charts below suggest, the sharp increase in downtown employment since 2010 seems likely to continue.

Downtown services employment — shown in blue at the bottom of the chart — has grown enormously since 1972, now accounting for most downtown jobs.

But overall downtown employment remained stuck at around 500,000 until 2010. That’s because other types of downtown jobs were disappearing. The central city once was a hub of light manufacturing, with printing in the South Loop and apparel-making in the West Loop. Over time, almost all of those jobs went away, offsetting growth in service jobs.

The next chart makes clear what happened in 2010. It combines all non-services jobs into one category and flips the order, putting services on top.

Non-services jobs bottomed out in 2010 and since then have risen modestly each year. Coupled with the continuing growth in services, that explains the big jump in downtown employment of recent years.

The charts also show why downtown gains are likely to continue. Services jobs, the chief driver of employment growth, have been increasing at a healthy pace for at least 46 years, notwithstanding the occasional downturn. So this is no blip. It’s a longterm trend.

If we make reasonable investments in infrastructure and avoid doing dumb things — neither of which is a sure bet in Illinois — there’s no obvious reason for the upward trend to stop.

The current pace of downtown employment growth — nearly 17,000 jobs a year since 2010 — isn’t likely to continue indefinitely. A more conservative figure, based on services growth since 2002, suggests that the longterm sustainable rate is 7,000 per year. The cautiously optimistic might prefer to find a sweet spot between those two numbers — say, 12,000 a year.

But that’s still a lot of jobs. At that rate, by 2030, employment in downtown Chicago would surpass 750,000.

It isn’t that the rest of the city won’t gain jobs. The neighborhoods have seen modest employment growth since 2010. But given the trend of the past half century, a neighborhood jobs boom isn’t in the cards.

Which isn’t bad. Because not only are a lot more people working in downtown Chicago, many more of them are choosing to live in the city. Not long ago, suburbanites commuting downtown via Metra outnumbered city residents who got to work on the L. Now, L commuters predominate, most of them living in the city, which helps stabilize neighborhoods that once were in decline.

And it isn’t only the affluent parts of Chicago that stand to benefit. The emergence of downtown as the region’s chief economic engine offers the best chance to lift people out of poverty that we’ve had in a long time. For most of the postwar era, until recently, the bulk of new jobs could be found in the suburbs, requiring cars. But downtown is readily accessible by mass transit from most parts of the city.

So lots of jobs are being created, and they’re easy for low-income city residents to get to.

There’s still the issue of what the workforce experts call “job-skills mismatch” — many impoverished city residents lack the qualifications that the available jobs require.

That’s a problem that putting more jobs in the neighborhoods won’t make go away. Except for the simplest types of work, employers aren’t likely to hire people whose only qualification is that they live nearby.

Economic development efforts in the neighborhoods isn’t futile. But, at best, they generate new jobs numbering in the thousands. Downtown, by comparison, produces new jobs in the tens of thousands.

Claims that “smart manufacturing” or some other breakthrough might change that picture significantly are wishful thinking, judging from the evidence.

Do downtown jobs require an MBA or other advanced degree? No, though the better-paying ones go mostly to college graduates.

Other jobs pay less. Among the fastest-growing categories in services are health care, social assistance, accommodations and food services. No one ever got rich working as a hotel housekeeper, dishwasher or hospital orderly.

It isn’t easy, but entry-level jobs can be a steppingstone. Efforts must be made to offer education and support, improve working conditions and provide a clearer path from entry-level to a position that pays a living wage.

The surest way to raise people out of poverty in Chicago is to get them into the downtown economy. That’s where the jobs are.

This is part of the series City at the Crossroads by journalist Ed Zotti, who takes an in-depth look at trends affecting Chicago and critical choices the city faces.

Email comments to: letters@suntimes.com.