In the wake of the dispiriting June 27 Trump-Biden presidential debate, many Americans are asking how we got these two candidates — viewed unfavorably by the majority — as the Republican and Democratic party nominees. And yet their nominations were all but locked up before most state primaries even took place, raising voter frustrations and increasing apathy.

It’s at least part of the reason why turnout in Illinois’ March 19 Republican and Democratic primaries sunk to a near-historic low, as just 19% of eligible voters in the state cast ballots.

“I think a lot of people would prefer, like, different candidates for both [parties’ presidential nominations],” said Jason Sullivan, 22, of the southwest suburbs, walking through the Daley Plaza Farmers Market at lunchtime. “I know a lot of Republicans hate Trump, and a lot of Democrats hate Biden. So it’s kind of unfortunate that’s the way things turned out — but that’s just how our country works these days.”

And the lack of candidate choices extended far beyond the top of the ticket this year. An analysis by Capitol News Illinois found that nearly 90% of primaries for hundreds of judicial, county and legislative seats on the ballot in March had just one, unopposed candidate or no one running at all. It’s the highest number of uncontested primaries in the state in at least 20 years, according to the news organization.

Do partisan primaries limit voter interest?

Some election experts say primaries themselves are a big part of the problem.

“Americans are exhausted by politics,” said John Shaw, director of the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University. “They think the two parties have moved to the far right and the far left: Don’t speak to them.”

Shaw said the problem is rooted in the redistricting process. In Illinois and most other states, the party in power draws the legislative maps. And they’ve gerrymandered congressional and state legislative districts to give their party an advantage. That means most candidates are easily elected and re-elected in the general election simply by having a “D” or “R” next to their name.

How this changes campaigns

“Well, it means that all you really need to do is focus on the primary voters and you don’t really need to appeal to the broad center,” Shaw said,

That’s led to calls for primaries that are more open and less partisan and for other changes aimed at getting more people to feel that their vote matters.

The partisan nature of the primary systems is part of what kept Colleen Getz, 34, of Deerfield, from voting. She said she and many of her friends don’t vote in primaries because they don’t identify with one party.

“Most people that I will ask, you know, or who describe their political views will say, ‘I’m an independent.’ Most people will say that,” Getz said. “So I do think that it’s divisive.”

A recent Gallup poll found that a record high percentage of Americans — 43% — say they don’t align with either Democrats or Republicans.

How states are changing primaries

Primary elections are used by political parties to nominate candidates to represent them on the general election ballot. How primaries are conducted and who can vote in them varies from state to state.

Illinois has what’s considered a partially open primary. You can choose whichever party’s ballot you want, but you can vote only for candidates from that party. And which ballot you select is public record.

Illinois voters can opt for a nonpartisan primary ballot, but there are no candidates on it — just local referendums. Yet there was a significant increase in the number of voters choosing nonpartisan ballots this year.

Open primaries, by contrast, require no party registration or affiliation. Voters choose whichever party’s ballot they want, and the decision is private. This system permits a voter to cast a vote across party lines in a primary election and is used in 15 states, including Michigan and Minnesota.

Some states are experimenting with no-partisan or multiparty primaries. These are different in that they are not intra-party contests, but rather all candidates, regardless of party affiliation, are listed on the same ballot. California has a top-two primary system. All candidates for state offices are listed on the same ballot, with their party affiliation. The top two vote-getters in each race move on to the general election even if they’re in the same party.

Open primaries not a quick fix

But some argue that open primaries don’t necessarily boost turnout or make candidates appeal to the middle.

“The candidates who win in open primaries are no more moderate than the candidates who win in closed primaries,” said Lee Drutman, a senior fellow with the Washington think tank New America who studies electoral reforms.

He pointed to this year’s U.S. Senate race in California, in which a progressive Democrat, Rep. Adam Schiff, and a far-right Republican, retired baseball player Steve Garvey, easily defeated more than 20 others on the ballot to emerge as the top two vote-getters and will face each other in November.

“It’s pretty clear that, if you’re looking to reduce partisan polarization in our politics and boost participation, open primaries are going to have zero impact, and it’s a waste of time and money to even pursue this as an approach,” Drutman said.

Still, there are proposals this year in six states — Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada and South Dakota — to move to multiparty primaries.

Ranked-choice voting

Another way to open the process that’s winning support in a handful of states, including Illinois, is ranked-choice voting.

“With ranked-choice voting, instead of selecting a single candidate on the ballot, you would rank the candidates in order of preference, any order you like, first choice, second choice, third, third choice down the list, as many or as few candidates as you like,” said Andrew Szilva, executive director of the nonpartisan advocacy group FairVote Illinois.

Szilva said that, if one candidate gets more than 50% of the first-place votes, that candidate wins. If there is no clear winner, an immediate runoff takes place — the candidate with the fewest first place votes is eliminated, and that person’s votes go to whomever their voters ranked second. If there’s still no clear winner, the process of elimination continues until one candidate gets over that 50% threshold.

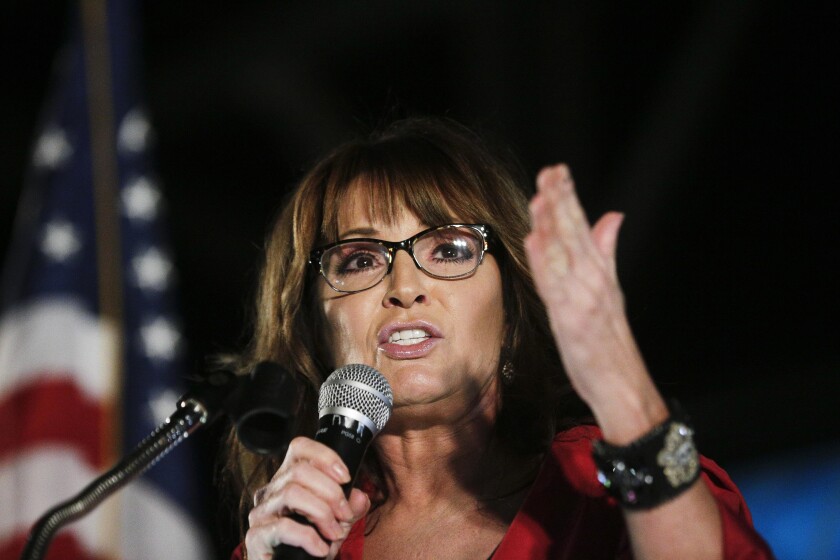

Because candidates will want to win second- and third-choice votes, Szilva said they will broaden their appeal. He pointed to the overwhelmingly red state of Alaska, where moderate Democrat Mary Pelota topped three more polarizing Republican candidates, including former governor and 2008 vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin.

“We’re seeing that elections become more civil,” Szilva said. “So there’s this incentive for the candidate to not really bash the other candidate ‘cause, if voters like that candidate No. 1, and I want to be their second choice, you sort of change the way you campaign.”

Szilva said ranked-choice voting encourages more diverse candidates to run for public office and boosts the chances of third-party and independent candidates.

The new voting system already is being used in at least 50 jurisdictions nationwide, including Maine and Alaska. Evanston will use it for city elections next year, and a task force will soon make recommendations on how it could be implemented in Illinois.

Whether it’s ranked-choice, open or multiparty primaries, many experts and voters say some change is needed to boost participation and give voters a greater say in who is elected.

After he voted at the Skokie courthouse in March’s primary, Amar Minhaf, 35, of Kenilworth, said there’s a cost to low voter turnout.

“I mean, it’s the voices of a few making choices for many at the end of the day if not a lot of people are voting,” he said.

The Democracy Solutions Project is a collaboration among WBEZ, the Chicago Sun-Times and the University of Chicago’s Center for Effective Government, with funding support from the Pulitzer Center. The goal is to help people engage with the democratic functions and cast an informed ballot in the November election.