It was Thursday, July 13, 1995. Temperatures in Chicago slowly crept upward from the high 90s earlier in the week. And they kept going up.

Mid-day readings at Midway Airport that day hit 106 degrees.

But it felt even worse. According to the heat index — measuring the effects of temperature and humidity — it actually felt like 126 degrees to an average, healthy human.

Anyone dependent on a fan only got churned, humid air.

Nighttime would only bring temperatures in the 80s.

Unbeknownst to Chicagoans and to their city government, the city was beginning a descent into a hellish oven from which it wouldn’t emerge for three days.

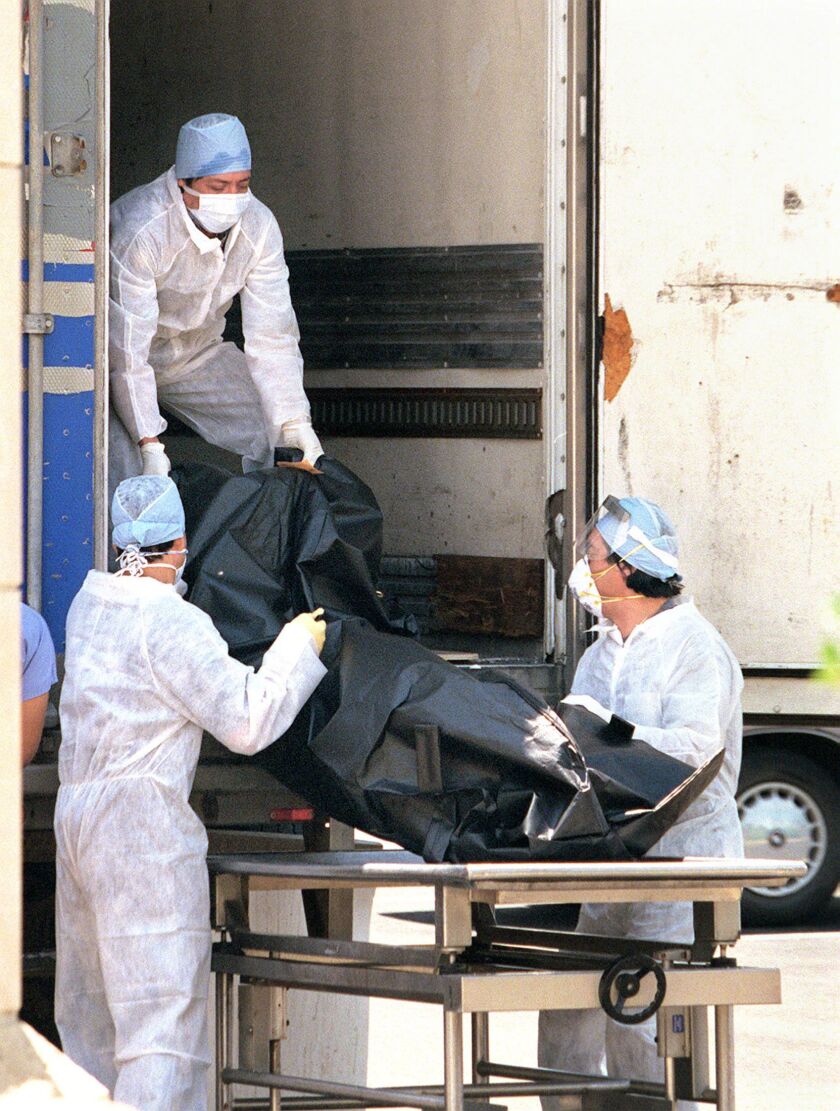

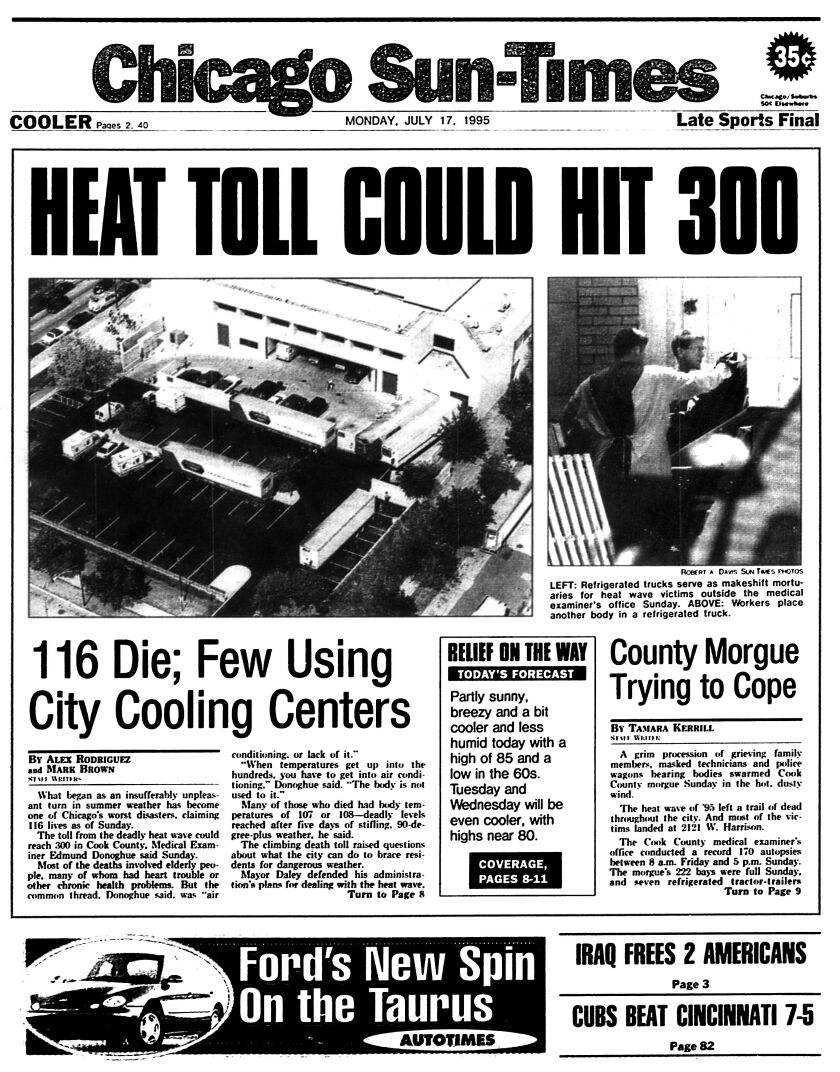

When the bake was over, in its wake were 739 fatalities — mostly the poor and elderly who lived alone. There were so many bodies that the medical examiner brought in a fleet of refrigerated meat-packing trucks to handle the overflow of bodies at the morgue.

Thousands more people were hospitalized as a result of the heat.

Lessons learned from the catastrophe two decades ago have informed how not only Chicago but also other urban areas respond to severe heat waves. Today recognized as potential natural disasters, cities have developed stringent heat emergency preparedness and response plans that include tending to their most vulnerable citizens.

“We’re far more prepared now than we were back then, physically, technologically, operationally,” says Gary Schenkel, executive director of the Chicago Office of Emergency Management & Communications.

Though created in 1995, OEMC became the city’s one-stop shop for emergency response after the 9/11 bombings.

“The history of 1995, going forward, certainly dictated the level of alarm and concern for the whole city in periods of heat concern,” Schenkel says.

“The most dramatic difference,” Schenkel says, “is that we’ve been able to develop a collaborative program integrating all city departments, with public utilities and the National Weather Service as partners. When we get indication we’re moving into a heat advisory, we immediately get all city department commissioners together and review the Emergency Weather Operations Plan.”

But that wasn’t the case 20 years ago.

The lethal heat wave caught Chicago off-guard, and much of the blame for that fell on a City Hall that had a heat emergency plan on the books — public advisories to be issued, cooling centers opened, checks to be made on elderly — but did nothing until it was practically too late.

It was on the second day of the heat wave that Dr. Edmund Donoghue, the Cook County medical examiner, found his morgue had become Ground Zero. Corpses from the previous day began to arrive, a barrage of body after body stacking up, filling every one of the 222 bays.

“The first inkling I got was about 9 o’clock Friday night, when my office called and said we’ve got 40 cases scheduled for tomorrow,” says Donoghue, who left in 2006 after nearly 30 years at Cook County. “In the history of the medical examiner’s office, we had never had that many. Typically, there were 17 cases a day.

“I asked the investigator, ‘What do you think is going on?’ He said, ‘Doc, they’re dying of the heat.’ When I got in the following morning, it was 85 cases.”

Mayor Richard M. Daley was on vacation in Grand Beach, Michigan.

People began flooding the city’s 911 system with heat-related medical emergencies and requests to check on loved ones. More than 16,000 calls came in that first day. A typical day brought 10,000.

First-responders were inundated.

“By 1:00, we’d been running all day,” paramedic Patrick Mroczek recalls. “By the third run where someone had passed out or felt ill from the heat, we all said, ‘This is bad.’ We knew there was a problem. The air conditioners were breaking down in all of the ambulances.”

Chicago funeral directors were inundated with requests to hold services for victims of the cityi’s deadly 1995 heat wave. This service for Ernest Young, 92, was one of 11 held on the same day at.A.A. Rayner & Sons Funeral Homes. Fourteen more were scheduled the following day at the funeral home, which normally had four or five services on any single day. Sun-Times file photo

On July 13, at the same time bodies were stacking at the morgue, hospital emergency rooms also were filling up.

“I remember we were called to these senior citizens’ buildings at Cermak and State three times after midnight that second day — to the 18th, 20th and 21st floors, and the elevators were out,” says Mroczek, who retired in 2008 after 33 years with the Chicago Fire Department.

“We had to hike up stairs each time,” he says. “Mercifully, only one patient went with us to the hospital. We had to carry her down.”

As E.R.s filled, city hospitals went on bypass status — unable to accept new patients. At one point, 23 were on bypass.

Paramedics were driving miles across the city seeking open beds.

“We were transporting further and further away,” says Mroczek. “Our response times went from an average of four to seven minutes to 25 to 40 minutes. Dispatch started requesting any ambulance available on the South Side, or North Side, then any ambulance citywide.

“Hospitals were calling all their people in. Cook County Hospital was in that big old building then. Several of the wings had no air conditioning, just fans that were of no use. People in there were sweltering. It was terrible.”

On that second day, record energy use overwhelmed Commonwealth Edison’s power grids, snatching air conditioning from 49,000 residents. Roads buckled. Chicagoans sought relief at packed city beaches and in the streams of 3,000 illegally opened fire hydrants. City Hall seemed oblivious.

“I was incensed that the mayor was on vacation and refused to come home in the face of such a tragedy and that nobody at City Hall responded in the timely manner needed,” says Bob Starks, founder of the Task Force for Black Political Empowerment.

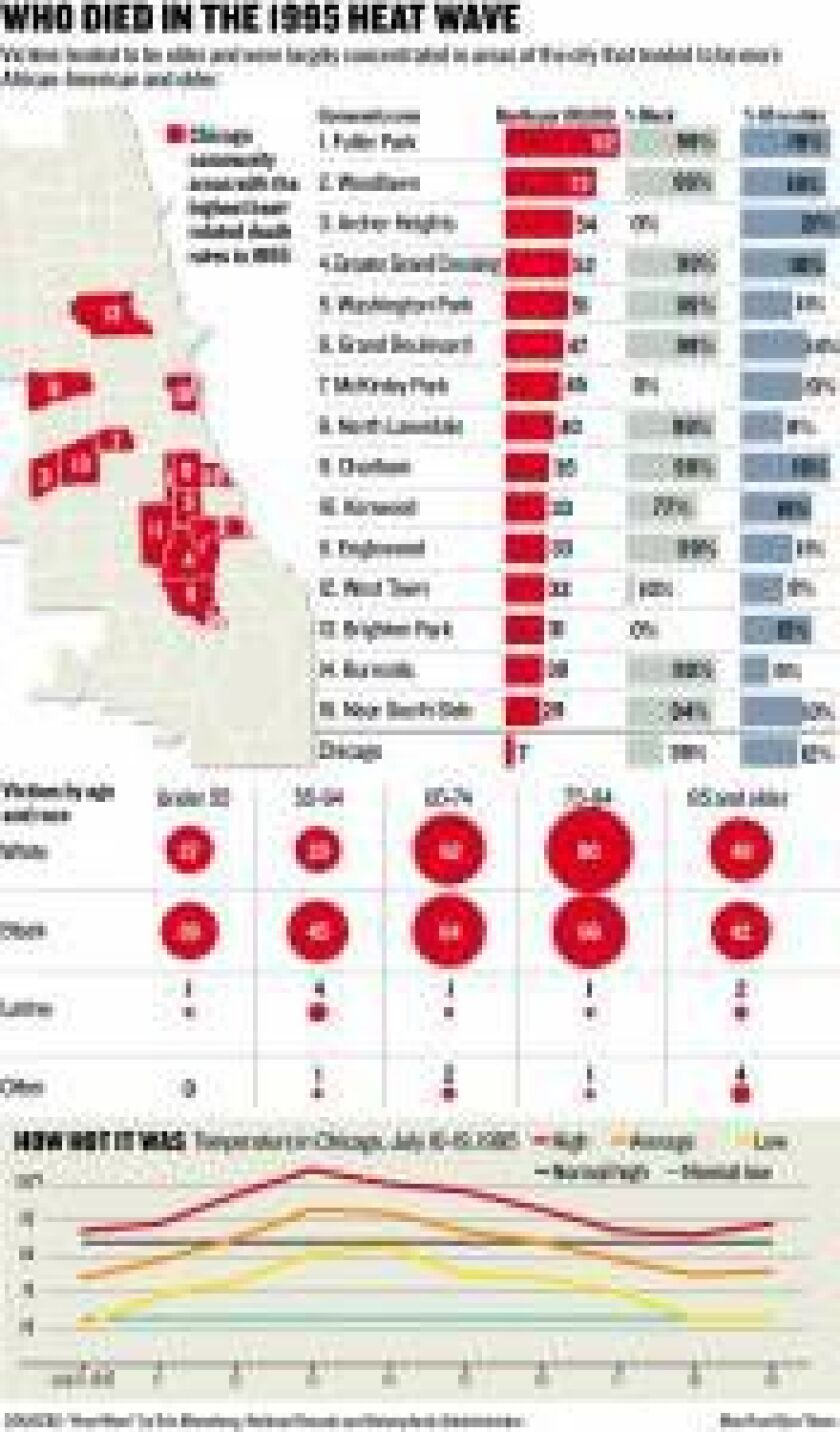

Stark’s group and the black community took Daley to task in the days following. The heat wave had killed 1-1/2 times as many blacks as whites. Latinos represented 2 percent of those who died from the heat.

“People were coming to us and reporting that their cousin, their aunt, their uncle, their mother, these hundreds of people, were in need. Nobody was responding,” says Starks, a political science professor at Northeastern Illinois University’s Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies. “They didn’t have enough cooling centers, enough city personnel going door-to-door to rescue these people.”

On the third day, the city declared a heat emergency, and finally City Hall began coordinating a response.

All first-responders were pressed into service. Refrigerated trucks were delivered to Donoghue to store bodies. Outside the morgue, ambulances and police squadrols — hauling corpses — kept queuing.

“The refrigerated trucks started rolling in about 5 Saturday,” says Donoghue, now regional medical examiner for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

“First-responders had been doing the best they could,” Donoghue says. “It’s at the upper echelons that information didn’t seem to get up to where more resources could be authorized.

“I’d called in all 15 of my doctors Saturday, along with students from the Worsham College of Mortuary Science to assist. We were able to get misdemeanor offenders in Sheriff [Michael] Sheahan’s work-alternative program to help us that week and called in our dental disaster squad, who normally would assist in identifying bodies in such disasters as airplane crashes, to work with us through the night.”

The heat wave broke on July 16, with temperatures returning to the low 90s. But because of the demographics of those who died — elderly people living alone — found bodies continued to be brought in all that next week, Donoghue says.

In the wake of the second-deadliest heat wave in U.S. history, a post-Disaster Survey Report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration confirmed that the National Weather Service had predicted the heat wave and issued warnings. Many of the deaths could have been prevented, the agency declared.

NOAA concluded that the city had not immediately recognized the public health emergency due to the rarity of a heat wave of that magnitude. Even if City Hall had recognized the threat, NOAA found, it had no official plan for heat emergency response.

“It was an unusually dangerous heat wave, with searing temperatures, tropical humidity, little cloud cover, and practically no cooling wind,” says New York University sociology professor Eric Klinenberg, author of a 2002 book analyzing what happened, “Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago.”

“But climate scientists recognized that the weather did not explain the massive death toll,” Klinenberg says. “Chicago’s vulnerability was due to brutal social conditions and gross policy failures.”

In Klinenberg’s book — reissued this month with a preface warning that cities like Chicago remain unprepared for such crises even as likelihood of such occurrences grows with global warming — he says politics and racism are equally to blame in Chicago’s 1995 heat wave.

“On the social side, what mattered most was the social isolation of poor residents living in the city’s most abandoned and racially segregated neighborhoods, places where the local environment discouraged people from going outdoors and getting support from friends and neighbors,” says Klinenberg. “On the policy side, the failures are too numerous to name.

“The city’s leaders were on vacation. They didn’t call a heat warning as the weather approached. The fire department didn’t call in additional ambulances when paramedics got overwhelmed. The health department didn’t know which hospitals were too full to take new emergency patients and which were open. The city didn’t even use the city’s heat emergency plan!

“Then, when the medical examiner began to report the initial fatality count, Mayor Daley questioned the scientific basis for his claims,” Klinenberg says. “This was just one of the many moves Daley made to deny and then downplay the significance of the catastrophe.”

But lessons were learned from the disaster, he says, pointing to 1999, when 110 people died during Chicago’s second-deadliest heat wave of the decade — fewer, though still catastrophic given an aggressive city response. A 2012 heat wave then claimed a fraction of that, 22 lives.

“I wasn’t here in 1995, but we used the opportunities we have under OEMC in 2012,” says Schenkel, who took over that agency in 2011.

A key component of the city’s plan seeks community responsibility.

“We urge residents to check on their neighbors, family members,” Schenkel says. “That has produced very positive results in the community. The events of the 21st century have really forced people to work together and be much more proactive. The reality is that without the kind of planning and unified execution that we now have through OEMC, we could well encounter what they did in 1995.”