Long before she became chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party, even before she first ran for public office, Toni Preckwinkle studied the career of another African-American political boss from the South Side, William Dawson, the legendary congressman.

As a graduate student at the University of Chicago during the 1970s, Preckwinkle wrote her master’s thesis about Dawson, who until his death in 1970 was the make-no-waves, vote-delivering, patronage-dispensing leader of the city’s black political machine.

“And the most fun I had was I went around to everybody who would talk to me who knew him and interviewed them. So I have a whole box of tapes of interviews, and that’s how I met John Stroger,” Preckwinkle told The HistoryMakers project in 2012, her eyes lighting up at the memory.

Stroger, then a Cook County commissioner and budding political boss on his way to becoming the first African-American president of the Cook County Board, proved to be a particularly helpful interview subject. After chatting for an hour with Preckwinkle, Stroger gave her a list of names of others to interview and told her she could drop his name to get their cooperation.

In pursuit this year of her long-held goal of becoming mayor of Chicago, Preckwinkle has campaigned in part by embracing her own role as a boss, though she says the party chairmanship never was part of her ambition, more an opportunity that presented itself.

Preckwinkle is a different sort of political boss than Dawson or Stroger, with whom her story would intersect several more times in the following decades.

Preckwinkle’s political roots grew out of Hyde Park’s liberal, independent tradition. And she has made her fair share of waves during a career grounded more in policy than patronage — notably flexing her independence as an alderman by voting against Mayor Richard M. Daley’s parking-meter deal.

RELATED

• Lori Lightfoot: ‘An opportunity to do big, bold things’

• Sun-Times’ 2019 Chicago mayoral, aldermanic voting guide

• Side-by-side: Lori Lightfoot’s and Toni Preckwinkle’s plans for Chicago

But her fascination with — and allegiance to — the Cook County Democratic Party also has been a recurring theme, right up to the present, when her party connections serve as both an important asset and a major liability.

Preckwinkle outmaneuvered remnants of the Democratic Machine to get elected Cook County Board president in 2010, then stepped up last year to replace her controversial ally Joseph Berrios as party chairman when Berrios was ousted as county assessor.

Unfortunately for Preckwinkle, that leaves her carrying the weight of being party boss at a time when voters want to break from that past, the same dynamic that allowed her to rise from relative obscurity as Fourth Ward alderman to lead county government.

After more than 27 years in office — 19 on the city council, eight at the county — Preckwinkle has established a no-nonsense image that friends say hews close to reality.

She really is “school-marmish” in private, too, they say, saying that’s to be expected from a former teacher.

And as much as she is a public figure, many voters surely don’t know how Preckwinkle got to where she is and who she is — from the complicated role that Harold Washington played in her rise, to her disdain for technology, to her ability to make a killer mac ‘n’ cheese.

‘Felt I had come to the South’

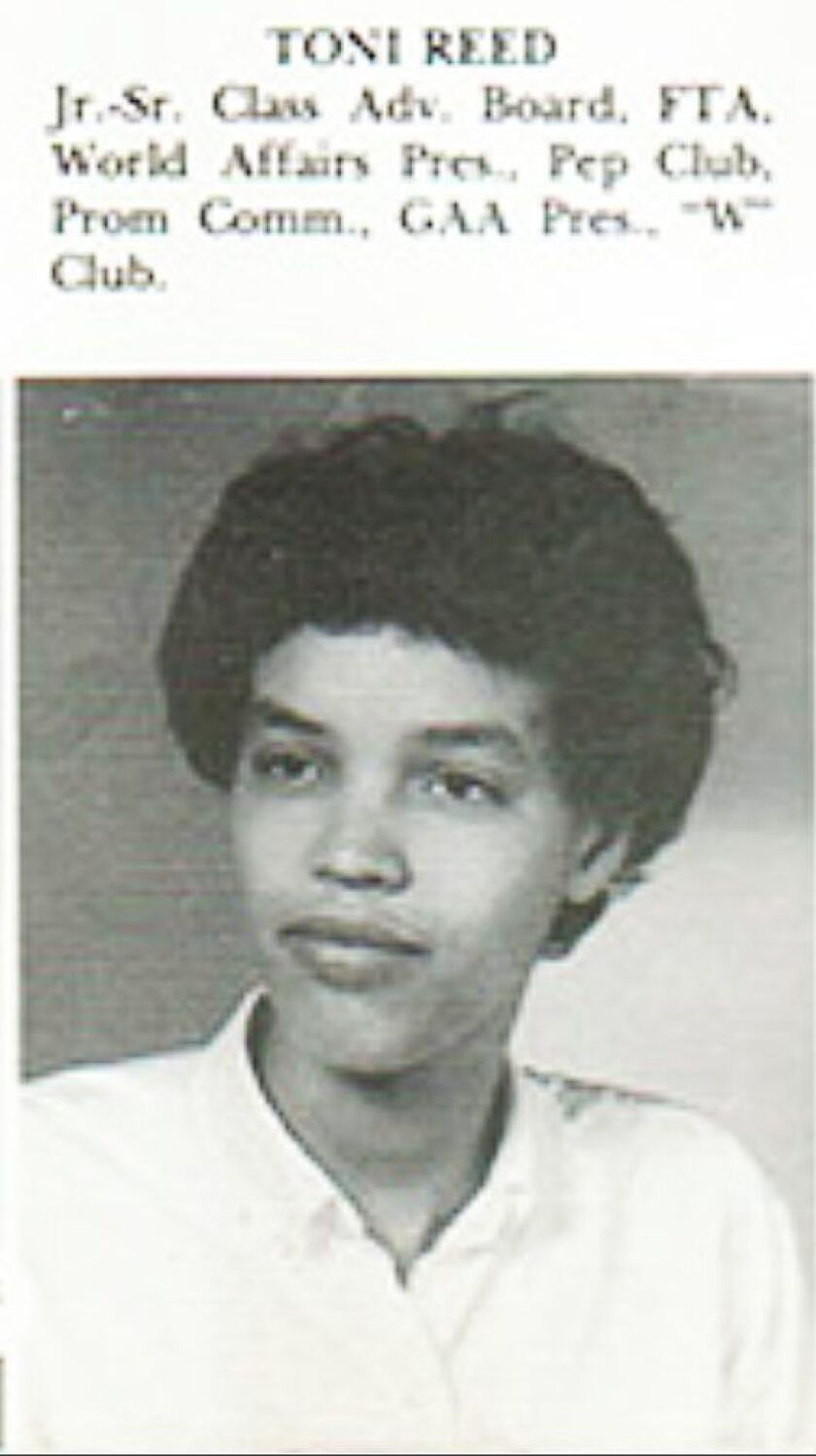

Preckwinkle was born Toni Lynn Reed in St. Paul, Minnesota, on St. Patrick’s Day in 1947, her birthday a happy coincidence for a future Chicago politician.

“My joke is that this is an Irish-Catholic town, especially for politics, and I’m not Irish-Catholic, but I had the good sense to be born on St. Patrick’s Day,” she told the Chicago Sun-Times days before turning 72.

Preckwinkle was the oldest of four children born to Samuel and Beatrice Reed. Her father, a World War II veteran, was a real estate appraiser for the Veteran’s Administration. Her mother was a librarian. Unusual for the time, both were college graduates.

Rather than live in St. Paul’s historic black neighborhood with their extended family, the Reeds raised their children in the town’s North End, where Preckwinkle says they were one of just two African-American families in her public elementary school.

In The HistoryMakers interview, Preckwinkle said her main memories of grade school were that she did well and had to fight her way home past bullies to protect her younger brother. She said bullies called them “n—–” but that this stopped by fourth grade, when she and her brother outgrew their tormentors.

At St. Paul’s Washington High School, Preckwinkle excelled in the classroom, where she was placed in an advanced curriculum, and athletics, playing volleyball, basketball and softball and high-jumping.

At 16, she volunteered for the campaign of a woman seeking to become the first black elected member of St. Paul’s City Council. Her candidate lost, but a seed was planted.

Preckwinkle never ran for class office herself, saying she assumed a 6-foot-tall black girl couldn’t get elected.

Still, her senior class voted her “most intelligent” as well as “best athlete.” But the yearbook adviser deemed it unfair to give both honors to one student and gave the best athlete title to someone else, Preckwinkle recalls with a hint of bitterness.

By graduation, Preckwinkle was eager to get away from St. Paul. At a friend’s suggestion, she applied to and was accepted by the University of Chicago, which she had never visited. It was 1965 when Preckwinkle arrived in Hyde Park, even then an integrated enclave in the nearly all-black South Side of a segregated city.

“Believe me, when I came to Chicago, I felt like I had come to the South,” she once said. “There was a black community in St. Paul, but black people also lived all over. And my sense of Chicago when I came here was that was not the case. … There weren’t exactly barbed-wire fences around neighborhoods, but psychologically that was how you felt a lot of times.”

‘Loved being a teacher’

At U. of C., Preckwinkle’s political activism tilted to the traditional. She volunteered in 1968 for fellow Minnesotan Hubert Humphrey’s presidential campaign and for future U.S. Sen. Paul Simon, who was elected Illinois lieutenant governor that year.

Preckwinkle said she avoided the antiwar demonstrations that summer at the Democratic National Convention, partly out of loyalty to Humphrey, partly out of concern for her safety.

In college, she met her husband-to-be Harry Zeus Preckwinkle, a tall, gangly white student from Oregon. Both were volunteering in a program that tutored kids in nearby Woodlawn. They were married in 1969, the year she graduated. Both became teachers.

“I became a history teacher because I wanted to understand why white people hated us so much,” Preckwinkle told interviewers Mick Dumke and Ben Joravsky many years later.

A student-teaching position with the Chicago Public Schools at a “pretty troubled” Calumet High School was a rude welcome to her new profession. She never taught again in the city’s public schools.

Preckwinkle went on to teach at two Catholic girls high schools, spending four years each at Visitation and Aquinas, with a two-year hiatus in between to work for the Illinois Capital Development Board during Gov. Dan Walker’s administration.

She wrapped up her teaching career with a year at the private Harvard School in Kenwood. With the birth of her son in 1981, Preckwinkle quit the profession.

Preckwinkle still introduces herself at campaign appearances as a teacher, though she hasn’t held a teaching position in nearly four decades.

Has she ever missed teaching?

“I loved being a teacher. It’s a great job,” she said.

But Preckwinkle said she never found a way to teach without devoting too much time to it, between time in the classroom and her responsibilities as the forensics coach.

She ended up, of course, in the 24/7 business of politics, but that was only after a decade holding other jobs, including three years as a city planner and three as executive director of the Chicago Jobs Council.

One of the great ironies of Preckwinkle’s political career — and this is an observation she makes herself — is that it probably never would have gotten off the ground if not for the death of Chicago’s first black mayor, Harold Washington.

‘Tony Rezko and I helped her win’

To this day, Preckwinkle likes to say she “beat the Machine” to get elected to the city council. Which is an oversimplification.

Preckwinkle had come up through the ranks of the Independent Voters of Illinois and directed field operations for the successful 1979 campaign of Lawrence Bloom for Fifth Ward alderman.

It took her three tries to oust Ald. Timothy Evans (4th), who’s now chief judge of the Cook County courts.

On her first two attempts in 1983 and 1987, she ran smack into the popularity of Washington, who endorsed his old friend Evans and afterward made him his city council floor leader.

Washington and Evans had come up through the Democratic Machine, though, by the time Washington was mayor, he had rebranded himself as anti-Machine.

As Washington’s voice on the council, Evans appeared politically invulnerable. Then, in 1987, Washington died while in office. Many of the mayor’s supporters thought Evans should succeed him. Instead, the council faction that opposed Washington helped install another African-American alderman, the Sixth Ward’s Eugene Sawyer, as mayor.

The ensuing rift among Washington’s supporters helped Richard M. Daley win the 1989 special election for mayor.

Some blamed Evans for causing the African-American community to lose control of the mayor’s office, among them Stroger, who was also the powerful Eighth Ward Democratic committeeman. Stroger was “very upset” with Evans. When Preckwinkle asked for his support to run for alderman again in 1991, he agreed to send his godson Orlando Jones, one of his most trusted political operatives, to help her beat Evans, according to Todd Stroger, Stroger’s son.

In her own telling of what finally made her a 109-vote winner in that 1991 race, Preckwinkle keeps it simple.

“Over time, I got to know more people and knew more about raising money,” she said.

Among the people Preckwinkle got to know was businessman Tony Rezko, who later was a key figure in the corruption probe of Gov. Rod Blagojevich and ended up serving eight years in prison.

In 1991, Rezko and his partner Daniel Mahru were little-known developers breaking in to the affordable-housing business.

“Tony Rezko and I helped her win her first election,” Mahru said in an interview.

He teamed with Rezko to rehabilitate hundreds of apartments across the South Side for low-income tenants, starting with a 44-unit building they bought in Evans’ ward in 1989.

“Everyone at City Hall liked the project,” Mahru said. “We couldn’t get Evans to return a phone call. We just needed his aldermanic approval. I made it my business to meet Toni because she was running against Tim Evans.”

Rezko, Mahru and their business associates gave $4,500 to Preckwinkle’s campaign in 1991 — which was good money for a ward race back then. Altogether, Rezko and his associates contributed $43,375 to Preckwinkle between 1991 and 2000 and helped raise more.

“I don’t know if they were having trouble with [Evans], but they helped me,” Preckwinkle said, acknowledging that she, in turn, supported them.

With a new ally as alderman, Rezko landed millions of dollars in government subsidies to rehab 292 apartments for low-income residents in Preckwinkle’s ward.

Within a few years, though, city inspectors filed lawsuits over a lack of heat and other code violations, and lenders foreclosed on the properties.

“They left the affordable-housing arena, and, when they did, they emptied the bank accounts so that the people who bought the properties basically had no reserves to deal with the deferred maintenance and other challenges of the buildings they owned,” said Preckwinkle, still miffed by what she sees as a betrayal.

‘Pulled herself up by her bootstraps’

A year after being elected alderman, Preckwinkle solidified her control over the ward by becoming Democratic committeeman and soon crossed swords with some of her old IVI friends by backing Machine candidates over their picks.

She built a strong ward organization and was easily re-elected four times, twice vanquishing a young lawyer named Kwame Raoul, a candidate she later would support for state senator who is now Illinois attorney general.

Preckwinkle distinguished herself on the council by supporting progressive causes and often voting against Daley’s budgets but also by supporting the mayor’s efforts to tear down and replace Chicago Housing Authority projects.

After John Stroger’s death in 2008 and the rocky tenure of Todd Stroger as his successor, Preckwinkle decided to run for county board president in 2010.

In retrospect, it might seem obvious Preckwinkle was going to prevail in a Democratic field that included the politically wounded Todd Stroger, Circuit Court Clerk Dorothy Brown and Metropolitan Water Reclamation District President Terrence O’Brien. But it was anything but at the time. It wasn’t until after she had the race sewn up that the big players in the Democratic Party moved to support her.

“Toni pulled herself up by her bootstraps,” said Delmarie Cobb, a political consultant who once counted Preckwinkle among her clients. “Nobody has given her anything.”

Preckwinkle has been pragmatic about taking help from the party’s regulars, campaign records show. Despite her fractious relationship with Daley, she accepted nearly $5,000 in assistance from the mayor’s campaign fund in 1999 when both were facing re-election challenges.

She also has gotten $12,950 in campaign contributions over the years from Ald. Edward M. Burke (14th) — before the 2018 Preckwinkle fundraiser Burke hosted at his home that now serves as a partial basis for an allegation by federal prosecutors that he tried to extort the owner of a Burger King franchise for a contribution on her behalf.

As county board president, Preckwinkle has made strides in criminal-justice reform and expanding access to health care for the poor, the latter helped considerably by the federal Affordable Care Act.

But an initial honeymoon period that fueled speculation of an earlier run for mayor cooled considerably after her attempt to help the county budget by imposing a “sweetened-beverage” tax that proved so unpopular it was repealed.

‘Idealistic but also realistic’

Friends say the Preckwinkle voters see on the public stage is very much a case of what you see is what you get.

“She’s kind of what you would call a plain Jane,” said Shirley Newsome, the longtime friend and ally Preckwinkle installed briefly as alderman when she moved to the county post. “What you see is the real deal.”

“Believe it or not, she is friendly,” Newsome said. “She comes across as stern or school-marmish. She can be bossy, yes. She can be somewhat free and unreserved. But that’s not necessarily her character.”

Stephanie Franklin, who traces her friendship with Preckwinkle to those long-ago Hyde Park campaigns, said Preckwinkle “has always been idealistic but also realistic,” someone who chooses her battles carefully.

Until recent years, the two would go antique-shopping together on weekends. Preckwinkle always had an eye for plain, Shaker-style furniture and collected jewelry, according to Franklin. Native American jewelry, Preckwinkle confirms.

Franklin said she still makes macaroni and cheese from a recipe she got from Preckwinkle that includes an egg and sour cream — the “best mac ’n’ cheese I ever had,” though she said Preckwinkle doesn’t really cook much.

While in campaign mode, Preckwinkle said she barely has time at night to walk the dog and go to bed, let alone cook.

The dog, a rescued pit bull named Don, belongs to Preckwinkle’s daughter Jennifer, 28, with whom she says she is staying while having work done on her own Hyde Park apartment.

After 44 years of marriage, Preckwinkle and husband Zeus got divorced in 2013. He moved to the Philippines, remarried and has another family. She declined to discuss the situation.

Her friends say Preckwinkle is a devoted grandmother to the three children of her son Kyle Preckwinkle, often taking them fishing and camping — a product of her Minnesota upbringing.

Unlike Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Preckwinkle is unlikely to ever be embarrassed by the disclosure of private emails. Preckwinkle is a self-described “Luddite” who doesn’t use a computer, never has and doesn’t even have an email account.

“How do I live without email? Very well, thank you,” she said.

After Daley’s long run as mayor, followed by Emanuel, Preckwinkle admits she’d started to think she might never get a shot at becoming mayor.

“I guess I’d sort of gotten to the point where I thought the stars were not going to be aligned,” she said.