Things were looking good for Al Jenkins when he went up against other hungry amateurs at Chicago’s 1960 Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions.

The Milwaukee heavyweight won the first round against a young boxer named Cassius Clay, who bested him in the second.

It came down to the final round, where, as writer Peter Ehrmann put it, “Al Jenkins’ right fist shot out, hammering his opponent’s jaw with almost enough force to change boxing history.”

But the dazed fighter managed to hang onto him.

“I couldn’t shake him off,” Mr. Jenkins told Ehrmann in a 2012 Milwaukee Magazine interview.

His opponent rallied. Two of the three judges made the future Muhammad Ali the winner.

Growing up, Mr. Jenkins’ son the Rev. Al Jenkins Jr. remembers, “He’d say to me, ‘If the ref would have done his job, son, we’d’a been outta here.’”

“I knew I’d taken my best shot,” Mr. Jenkins told Ehrmann.

Within months, both boxers were at the regional Olympic trials in Louisville, Kentucky. When Mr. Jenkins and his then-wife Seporial went to see a John Wayne movie. the future champ asked to join them.

“Mom said he kept talking — about how pretty he was and when he walked in the room, all the ladies look at him and how fast he was,” the son said.

She asked: “Can you be quiet so we can watch the movie?”

“He continued to talk about how fast and how pretty he was and how he was gonna shock the world,” according to the son.

And, to Mr. Jenkins, he added: “I gotta get past you, Big Al.”

He won Olympic gold in Rome and floated like a butterfly into boxing history.

But Mr. Jenkins remained an amateur. The following year, he told the Milwaukee Journal he was going to “do a lot of rope skipping and boxing” to prepare for another Golden Gloves, hoping to turn pro for “a better future than manual labor.”

He won the 1961 national Golden Gloves heavyweight title. But a professional career never materialized for Mr. Jenkins, for whom services were held in August after his death at 83.

He’d been living with his son in South Holland. But after a diabetic reaction and a fall he spent time in a rehabilitation facility, his son said.

Family visits were limited because of COVID-19 restrictions. About 13 days after he arrived at the rehabilitation center, Mr. Jenkins — malnourished, dehydrated, with open sores — was transferred to Ingalls Memorial Hospital, according to his son.

After about three weeks at Ingalls, he improved and went to a second care facility but died within about 14 hours, his son said.

Though his father’s cause of death was listed as pneumonia, diabetes and a condition that complicates swallowing, Al Jenkins Jr. said he has filed a complaint with the Illinois Department of Public Health about the care his father received at the first rehab facility.

Mr. Jenkins was born in Jackson, Mississippi, the son of Lula and Clarence Jenkins, and grew up in Milwaukee, where he didn’t hesitate to take on bullies.

“He favored the kid that was being picked on,” his son said. “He’d ask, ‘Why are you picking on him? Pick on me.’”

Around 18, he was convicted of armed robbery and served time at Wisconsin’s Waupun Correctional Institution. He knew how to handle himself in a street fight. In prison, he learned “boxing-ring fighting,” his son said.

Poor eyesight didn’t help his pro prospects. But the bigger issue, his son said, was “he got back in trouble.” Within a few years of his Golden Gloves championship, Mr. Jenkins was back in jail.

“I picked up a pistol like a fool and helped a guy rob another guy,” he told Milwaukee Magazine.

After getting out, he committed another armed robbery.

In prison a third time, Mr. Jenkins decided to go straight and get his GED. In 1977, he earned an associate’s degree from Milwaukee Area Technical College.

“He was very knowledgeable. He could have been on ‘Jeopardy.’ He knew geography, world history,” his son said. “He was fluent in Spanish. He was a stickler for English. He helped me get through algebra.”

Mr. Jenkins worked at a packinghouse and at A.O. Smith foundry in Milwaukee.

Young men sought him out for advice, according to his son: “Dad was somebody — not only because he was my father, but he was others’ fathers as well.”

Mr. Jenkins “got clean and sober in 2003,” according to his son. A doctor told him to quit drinking and smoking: “The next day, without treatment or patches, he stopped.”

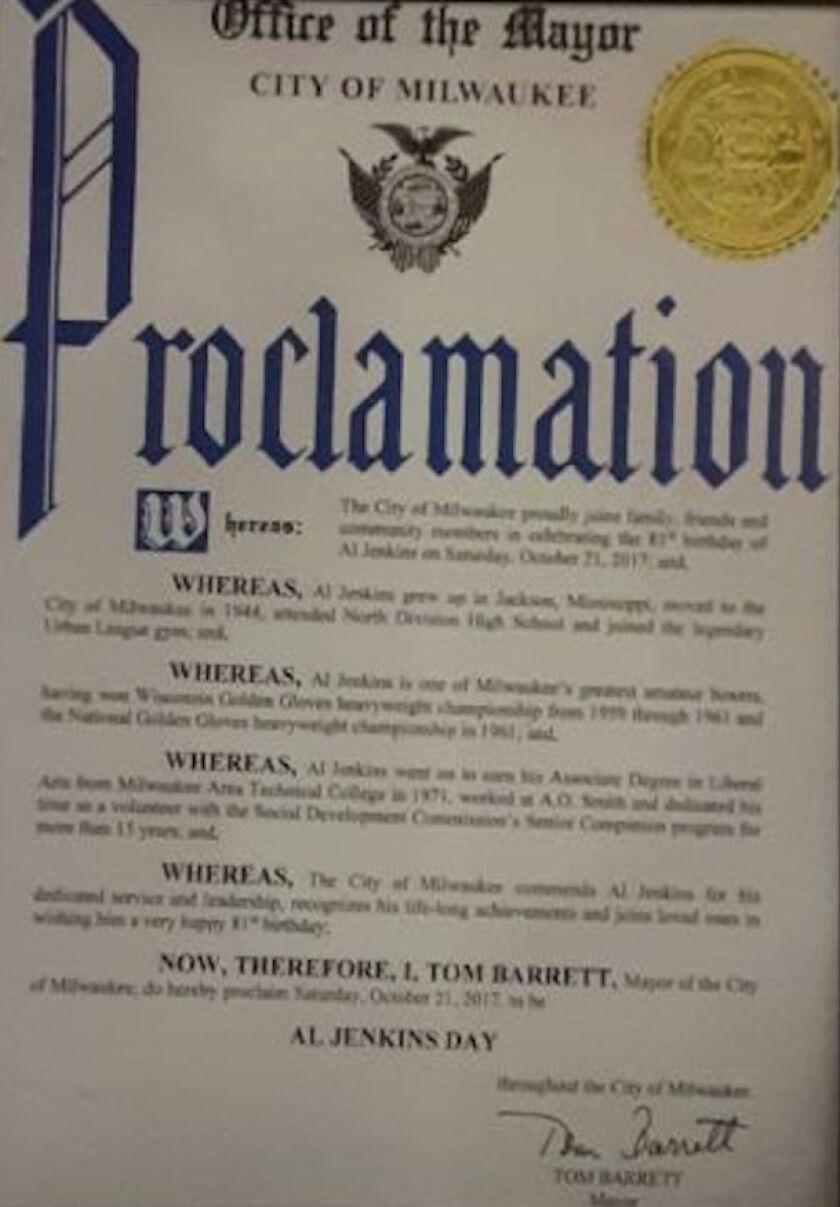

At 70, he started working security at Tabernacle Community Baptist Church in Milwaukee. And he volunteered for 15 years as a senior companion with the Milwaukee nonprofit Social Development Commission, winning praise from Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, who proclaimed Oct. 21, 2017, Al Jenkins Day and called him “one of Milwaukee’s greatest amateur boxers.”

Mr. Jenkins is also survived by five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

He told Erhmann he was proud of his boxing success: “It was the only thing I did well that wasn’t destructive.”