In Uganda, Celestine Mugisha offered the parents of the woman he wanted to marry a dowry — 4 million Ugandan shillings, three goats and one cow.

It helped Mugisha win the hand of Winniefred Akello, a woman he met at the refugee settlement camp where they both worked.

“I was caught by her appearance and her behavior,” Mugisha said of his wife. “She’s spiritual, and she’s good, and I wanted to take the time to learn more about her . . . because that’s the kind of woman I wanted.”

Their wedding in September 2016, secured by a dowry equivalent to about $1,088, marked the start of a new life but also a goodbye party.

The couple spent only one night together as husband and wife.

The day after their wedding, Akello had to travel back to the camp where she and her husband were working and, days later, Mugisha moved to a transit center, where he would wait to fly out of Uganda.

He was finally able to go to the U.S. as part of a refugee resettlement program.

During that period, Akello would travel by bus for hours every weekend — 10 hours if the bus wasn’t delayed, 16, sometimes, if it was — from the camp to the transit center, calling her husband on the phone.

Since Akello wasn’t authorized to resettle at that time, she wasn’t allowed into the center.

“And we would just wave — and wait,” Akello said.

Mugisha was too far into the resettlement process for Akello to come with him. After he arrived in Chicago, Mugisha applied for Akello to join him in the U.S., but the process is long and tedious.

While he was away from his wife, Mugisha was never certain that he would see her again.

The wait finally ended in January, more than three years after they took their wedding vows.

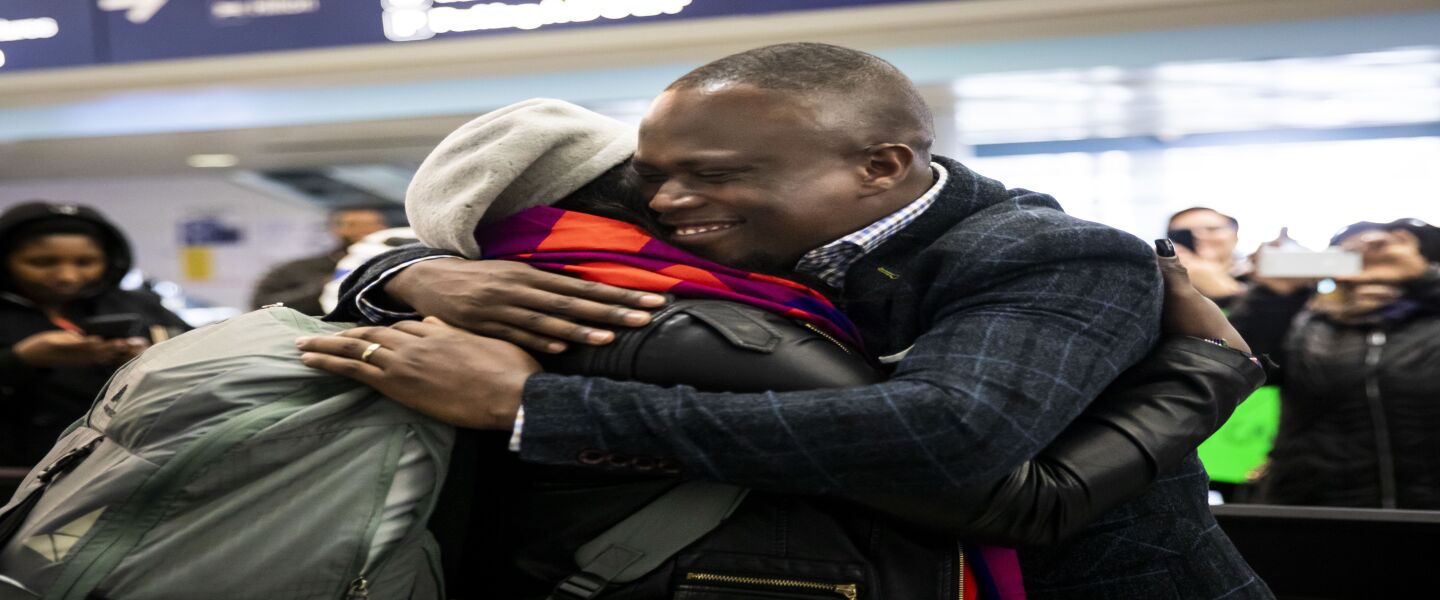

After a 17-hour flight, Mugisha and Akello had a teary reunion in January at the international terminal at O’Hare. Except for a brief overseas visit in 2018, they had lived apart about 30,000 hours.

“I was overexcited, I was overwhelmed,” Akello said, describing their teary reunion hug. “I could not believe I was seeing him I thought actually ‘maybe I’m dreaming’ and I wanted to pinch myself so I could wake up, but it was reality.”

When the two would video chat before her arrival, Akello would ask Mugisha to describe what snow was like.

“Is it like salt? Is it like flour? Is it like, you know, I always give him examples of the fridge — like when you’re in the fridge . . . and he’s like ‘when you come, you’re going to see.’”

Two days after she arrived, Akello got her chance to see it. It took some getting used to, like the country she now calls home.

“To me, it just feels like it’s a dream come true. It is something that I dreamed of, and it’s something that I wished to happen, and I am so glad that it happened finally. The first time it felt like it was not real, but I think it’s becoming real.”

Now, they’re spending their first Christmas together and they’ll ring in the New Year together, too.

The couple’s home is decorated in the vibrant reds of the Christmas season, with poinsettias in the entryway and red pillows on the couch, and red-and-white curtains hung over the doorways leading into the home and to other rooms in the house.

The couple quickly went from marveling at the snowflakes of a Chicago winter to enduring the isolation, and hardship, of a global pandemic that upended their plans.

Though no one in their immediate family has contracted the virus, Mugisha lost a relative earlier this year to it. In September, the couple suffered a miscarriage.

For now, they are focusing on what has gone well this year. Both have jobs — Mugisha was even promoted — and they have kept an optimistic attitude, one that’s rooted in their happiness of being reunited.

“I’m glad that even when we go through all this I have someone to lean on,” Akello said. “I have a shoulder to cry on, that even when things get hard he holds my hand and he’s like, ‘you know what, we are together in this and we’ll go through it,’ so . . . that keeps me moving, knowing that . . . we can still do better together.”

Having his wife at home — and making a home together — has been “awesome” for Mugisha.

“I feel like a husband now,” Mugisha said.

Celestine Mugisha and his wife, Winniefred Akello, embrace at O’Hare International Airport as they are reunited after living apart for more than three years on Jan. 22. Mugisha and Akello were married in Uganda in September 2016 and, days later, Mugisha moved to Chicago as part of the United States’ refugee resettlement program. More than three years later, Akello was also resettled through the program.

Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Sun-Times

Typically, Mugisha’s family doesn’t exchange gifts for the holiday, but his family would sit down together and share a meal, reflecting “on what has been good and what has not worked out and what we think about the year that is coming,” Mugisha said, adding that though gifts aren’t part of the tradition, he gives Akello something “anytime I come across a gift.”

Not being together for previous Christmas holidays was “something that was very hard for us,” Akello said.

“I’m so grateful that now I’m going to celebrate with him for the first time,” Akello said.

Resettlement — and especially reunification — doesn’t happen for everyone.

A member of the Tutsi ethnic group, Mugisha has been a refugee since he was 9. He fled with his family from the Democratic Republic of Congo to escape persecution, and they settled in Uganda.

It was in that country, at the Rwamwanja Refugee Settlement, in June 2015 that Mugisha met the woman who would become his wife — both worked at the camp as field facilitators.

The two kept their relationship quiet; employees weren’t supposed to date. Instead, they texted and talked on the phone when their workdays were done.

Shortly after he arrived in Chicago, Mugisha applied for Akello to join him and his family and resettle in the U.S.

They had been separate ever since, except for a weeklong visit in 2018.

“Leaving Uganda was not because the place was bad, but because my family and I, we are looking for safety from people who have been looking or hunting us down due to our ethnicity,” Mugisha said. “So, there was kind of ethnicity cleansing back in Congo, so some people were crossing over to Uganda to still hunt us down.”

Since Mugisha has been here, fewer and fewer refugees have been able to settle in the U.S.

In 2016, the U.S. welcomed nearly 110,000 refugees, which is just a little bit above the historic norm, said Jims Porter, the manager of communications and advocacy for RefugeeOne, which helped Akello resettle. On average, that number is about 95,000 a year.

In October, President Donald Trump set the refugee admissions limit for fiscal year 2021 at 15,000.

Along with a 2017 travel ban, President Donald Trump’s administration also sought to allow states the ability to turn away refugees looking to resettle.

When that executive order was blocked by a district court, a spokeswoman from the White House said the court “robbed millions of American citizens of their voice and their say in a vital issue directly affecting their communities.”

President-elect Joe Biden said earlier this month he plans to raise the annual refugee admissions cap to 125,000, a number that he plans to increase over time “commensurate with our responsibility, our values and the unprecedented global need,” and he will work with Congress to create a minimum admissions number of at least 95,000 refugees annually, according to his website.

“Even with the changes to the refugee admissions ceiling in January when President-elect Biden takes office, it will take some time before refugee arrivals start to pick back up again because the pipeline has basically been emptied,” Porter said. “We expect there to be a little bit of time before arrival starts picking up again and we anticipate that by next summer we’ll start to see the influx in arrivals that we’re expecting.”

Rebuilding that infrastructure likely means agencies hiring people who understand the resettlement process and rebuilding programing to help those who are in the process of resettling or who have been in the U.S. for some time.

RefugeeOne helped 1,500 refugees and immigrants from 50 different countries in 2020 — including Akello, whom they helped get settled in Chicago. She was one of the 177 new arrivals the refugee agency helped welcome this year, Porter said.

The couple expressed hope the Biden administration will do more in 2021 than they were able to this year.

“I hope things will change — that immigrants, refugees, Americans . . . will all have an equal chance,” Mugisha said.