Who knew when Ruth Apilado sent out the first thousand copies of AIM (America’s Intercultural Magazine) from a home office at 73rd Street and Eberhardt Avenue in 1973, that she still would be receiving submissions of poems, short stories and essays at age 113?

When I first met Apilado in 1977, she told me she had retired from teaching in order to launch a publication to promote racial harmony. It had been a dream of hers since the 1960’s, when she drove from Chicago to Mississippi with her son, knocking on doors to extol the benefits of integration, cautioning young Myron, “If you see me give a signal, run like hell.”

I was a teacher and an aspiring writer, and I listened closely as she talked about racial conflict, education and her theories on writing and literature. She had published “The Joneses” in 1950, a novel about the travails of an urban black family that received an honorable mention at the Midwestern Writers Conference.

I found her charming, funny, brilliant and, though barely five feet tall, slightly intimidating.

When I last spoke on the phone with Ruth, when she was only 103, her intellect was undiminished. But in a recent phone call with Myron, a retired vice president of minority affairs at the University of Washington, I learned that her memory was failing now, and that she had moved to an adult family home close to him near Seattle.

***

I was 27 when I mailed my first short story to AIM. It had been rejected by Playboy, Redbook, and Esquire, and I weighed whether to invest in any more postage. Then a letter arrived from Apilado, who wrote that she was interested and wanted to talk.

We met that week, and she explained that she liked the writing, but that my story — about a man’s losing struggle with alcohol and gambling — never gave the reader a reason to read on.

That was the intimidating part: her knowing immediately what I had only vaguely sensed.

Under Apilado’s guidance, I would work through several revisions of the story, one of which finally appeared in AIM’s July/August issue of 1978.

I can still see her face as she leaned forward in her chair, smiling brightly, telling me to call at any time since she seldom slept. She said she listened, instead, to the all-night radio show of Larry King, whom she swore must be a Black man.

Our early meetings transitioned to a regular Wednesday afternoon session, where I would join Ruth and several staff members in putting out the magazine, proofreading stories and judging submissions.

It would grow dark by the time I arrived home, and my wife, Marianne, asked me once about all the time I spent at the house of a woman she had yet to meet. So I confessed everything: That I loved my time at AIM: The staff’s gossip, their stories, their laughter. And my fantasy that Ruth was like my Gertrude Stein: A 69-year-old mentor to a twenty-something fledgling.

Little AIM magazine, of course, was hard pressed to meet Gertrude Stein’s standards, or to attract Hemingway-caliber contributors. But it did get essays on the topic of race from notable writers such as Thomas Cottle and James Alan McPherson, and contributions from the poet Henry Blakely.

Husband of Pulitzer Prize winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks, Blakely was another writer unable to resist Ruth’s contagious optimism, and he soon assumed an active role for the magazine.

I was starstruck by Henry, not just because of his wife’s celebrity, but also because of his own. As a result of “Windy Places,” his collection of poems featuring life on Chicago’s South Side, he was known as the “poet of 63rd Street.” And one snowy afternoon, Henry gave me the best advice I ever heard about writing. I had been telling him that after reading John Updike, I felt like a fraud, exposed by the spellbinding prose and profound insights of a real author.

“Take a closer look at Updike,” Henry said. “All he’s really doing is working his butt off to observe every detail in the moment, and to get it on paper as truthfully as he can.”

***

I left AIM after accepting a teaching job at a college farther away. But AIM never left me.

I remember an evening in 1997 when Eddie Two Rivers, a member of the Ojibwa people whose short story collection “Survivor’s Medicine” would win the American Book Award, came to my college for our visiting artists program.

Following his reading and Q.& A. in an auditorium full of students, Two Rivers confided: “I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Ruth Apilado.”

He had been a “nobody,” he said, reading poems for drinks in poetry slams at Uptown’s Green Mill. But, he said, Apilado had faith in his work when few others did, helping him build a career.

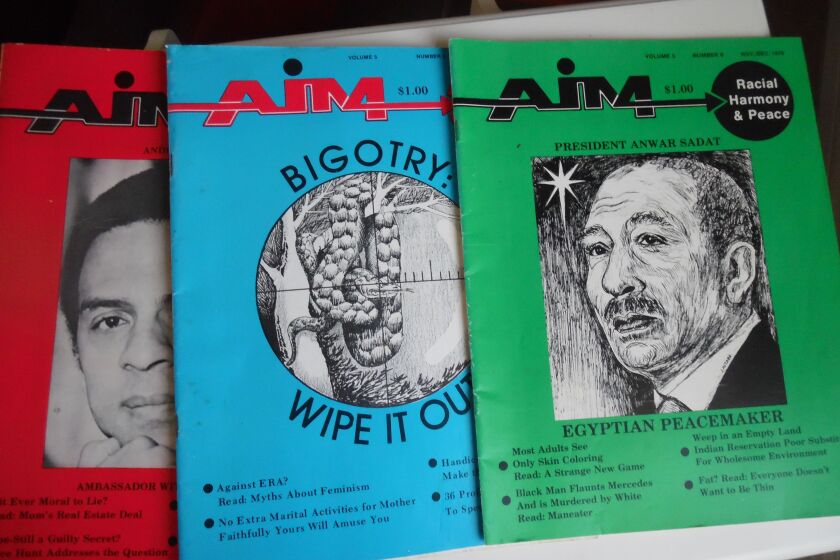

AIM would persist in its mission, even as Ruth turned the reins over to Myron and stepped down to associate editor. The magazine downsized from a bimonthly to a quarterly periodical, before circulation ceased entirely in 2007. Nonetheless, vestiges of its existence online, such as at WritersCafe.org, continue to prompt hopefuls to mail manuscripts to AIM’s University of Washington address.

When I asked Myron about his mother’s influence, he said his mission at the university mirrored AIM’s in many ways: “We helped under-represented minorities and economically disadvantaged youth to receive an education and pursue the American dream.

“I also get my idealism from her,” he added. “Though she’s always been a lot smarter than me.”

Gerontology Research Group lists Ruth as the country’s tenth oldest supercentenarian, born on April 30, 1908. She remains the oldest living Illinoisan, not to mention our oldest living civil rights activist, whose generosity, hope and love for all human beings is more sorely needed today than ever before.

David McGrath is emeritus professor of English at the College of DuPage and author of “South Siders,” a collection of essays. He can be reached at mcgrathd@dupage.edu.

Send letters to letters@suntimes.com.