McKinley Morganfield was born in rural Issaquena County, Mississippi, in 1913, the son of a sharecropper who played guitar on weekends.

His mother died not long after he was born, and he was raised by his grandmother.

She’s the one who gave him the nickname “Muddy,” stemming from his “muddying” for fish in a nearby creek. And when he picked up his first musical instrument, the harmonica — moving on to guitar in his teens — no one could have predicted Morganfield was destined to become the international blues legend “Muddy Waters.”

That would come after he headed north in the Great Migration, settling in Chicago.

And on Thursday, the home in the South Side North Kenwood neighborhood where the blues icon lived and raised his family moved a step closer to becoming a city of Chicago landmark, granted preliminary landmark status by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks.

“Muddy Waters was one of the most important figures in the development of the distinctive electrified sound that came to be known as the ‘Chicago blues.’ Muddy Waters skillfully married the raw acoustic Delta blues he learned in Mississippi, with amplification, to create a powerful new urban sound,” Kendalyn Hahn, project coordinator at the Chicago Department of Planning & Development told the commission.

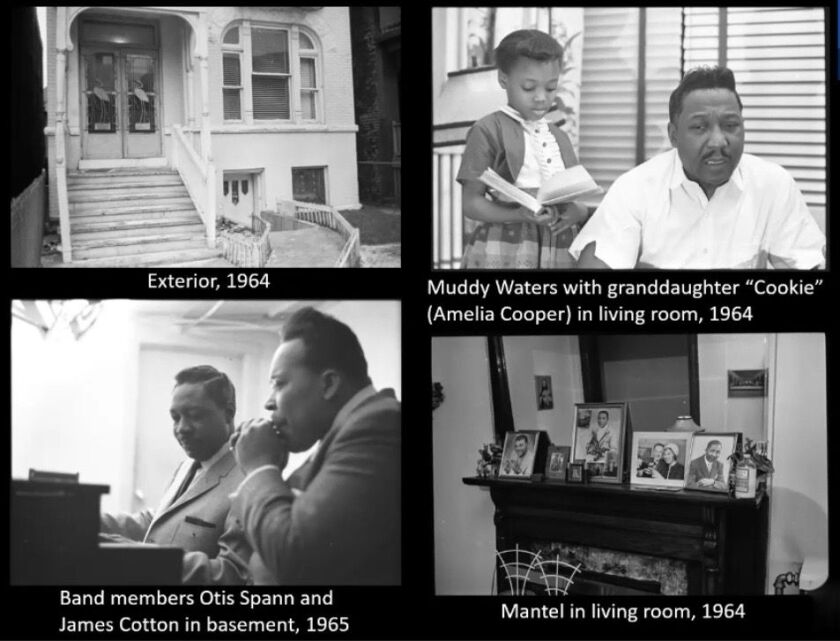

“This 1891 structure served as the home of the blues musician and his family from 1954 to 1973. And musicians who came to record or perform in Chicago made the home an unofficial center for the Chicago blues community, a community largely composed of African Americans whose gifts to the world not only shaped American popular music and subsequent generations of musicians, but one which gave the world a uniquely American art form, which speaks to the incredible resilience of the human spirit,” Hahn said.

The property at 4339 S. Lake Park Ave. is owned by Waters’ great-granddaughter, Chandra Cooper, who is converting the brick two-flat — where Waters lived on the first floor, rented out the top floor and had his recording studio in the basement — into The MOJO Muddy Waters House Museum. The preliminary designation passed unanimously.

The project is among burgeoning efforts to honor Black history in a post-George Floyd era, and part of a wave of house museums — including those honoring Emmett Till and Mamie Till Mobley, Phyllis Wheatley, and Lu and Jorja Palmer — that nearly got blocked by a failed ordinance earlier this year by Ald. Sophia King (4th) to limit them.

The Waters house is in the 4th Ward, and while Cooper and King have sparred over roadblocks in recent months, King on Thursday spoke ardently in support of the designation.

“My family comes from the Mississippi Delta. And so this is truly personal for me as well. My grandfather would be proud of me, because he taught me to drive in the backwoods of the Mississippi Delta. My mother picked cotton there. My uncle had to flee there when he was 16 because of fear of lynching,” King said.

“So I lived these stories. To have somebody like Muddy Waters who really put the blues and rock ’n’ roll on the stage, not just here in Chicago but across the country and the world, I’m personally proud. All of the challenges I know he was faced with to break down such barriers and do such significant things — this is a no-brainer for me.”

Arriving in Chicago in 1943, Waters played house parties at night for extra money, eventually becoming a regular in local nightclubs. By 1948, Chess Records released his first hits, “I Can’t Be Satisfied” and “I Feel Like Going Home,” and his career took off.

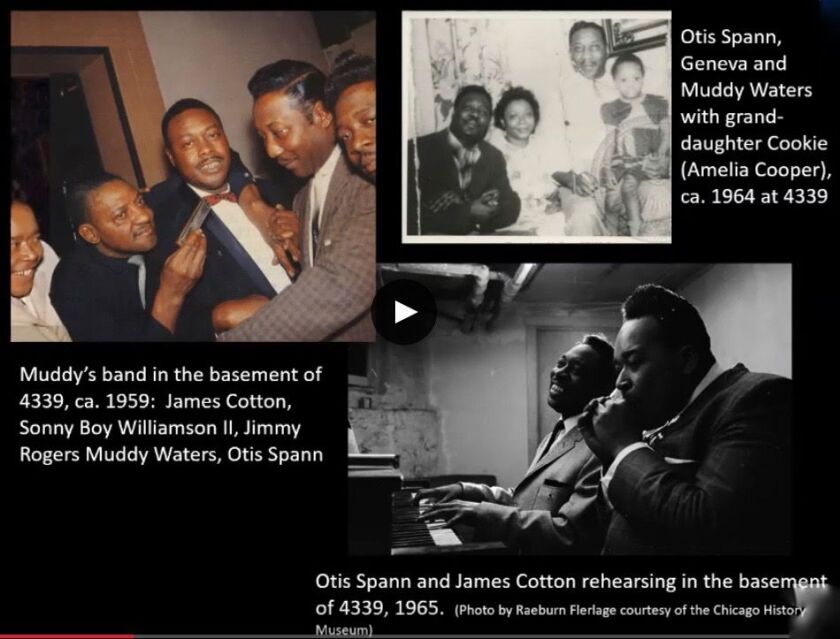

By the early 50s, his blues band, which at one time or another comprised musicians who went on to make their own mark — Otis Spann, Little Walter Jacobs, Jimmy Rogers, Elgin Evans, Sonny Boy Williamson, James Cotton — had become one of the most acclaimed in history.

Waters’ classics topped charts, becoming standards in the repertoires of English rock ’n’ roll bands of the ’60s, including The Beatles. The Rolling Stones took their name from Waters’ single, “(Like a) Rolling Stone.”

“On behalf of the family of McKinley Morganfield, we believe it essential for the legacy of African American history that this home be designated a landmark,” Chandra Cooper told the commission, accompanied by her mother, Waters’ granddaughter, Amelia Cooper.

Muddy Waters’ granddaughter, Amelia Cooper (l), who grew up with her grandfather, blues legend Muddy Waters, in his home in the North Kenwood neighborhood and Waters’ great-granddaughter, Chandra Cooper, spoke in support of preliminary landmark status for the home, granted Thursday by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks.

Sun-Times Media

Amelia Cooper lived in the home with her grandfather from 1956 to 1973. Waters moved his family there in 1954, purchasing it in 1956. Independent record companies like Chess, King, Vee Jay, Chance and Parrot, and distributors like United and Bronzeville were then headquartered around Cottage Grove from 47th to 50th streets, and the home became a gathering place for musicians welcomed at all hours.

At one time or another, legends like Otis Spann, Howlin’ Wolf and Chuck Berry stayed on the top floor. Waters lived there until after the death of his wife in 1973. He moved to suburban Westmont, where he lived until his death on April 30, 1983.

“I didn’t think I was going to be that emotional, but just seeing the pictures, and thinking of him and the struggle we went through, it was overwhelming,” Amelia Cooper said later.

“When I was born in 1956, my mother brought me home to that house. When Chandra was born in 1970, I brought her home to that same house. We have a lot of love and pride for that house. This has been a hard fight, and I’m proud of Chandra for not giving up.”