Mayor Lori Lightfoot, looking to boost Chicago’s economic growth, rightly laments that the city hasn’t produced a comprehensive land-use plan since 1966.

The closest thing the city has to a land-use plan — its zoning map — is at odds with what she wants to do.

Chicago needs a new plan. And fixing the messed-up zoning system needs to be part of it. Otherwise, the city has little chance of growing, much less reaching the mayor’s goal of 3 million people.

Huge swaths of the city, including many of its most prosperous neighborhoods, have been downzoned to single-family use. Often, these areas are densely built up. Yet the only thing that can be built on most lots is a single-family house, in some cases a two-flat.

The zoning often bears no relation to what’s on the property now and defies common sense.

Take the corner of Irving Park Road and Hermitage Avenue, which is about 100 yards from a CTA Brown Line station. There’s a six-flat there — a logical use. But the lot is zoned RS-3, a single-family designation.

City Hall favors transit-oriented development, which calls for higher density at locations like this one near L stops. But what the zoning map says is that, at this corner, you’re only allowed to build a house.

There’s wide agreement that Chicago needs to grow. But wholesale downzoning, which has been happening for decades, is pushing the city in the opposite direction.

City officials have been considering a proposal to downzone Andersonville south of Foster Avenue — a dense area of roughly eight blocks where single-family homes account for 16% of the housing. The current zoning — RT-4 — allows for three-story condo buildings here.

A number of condo projects have been built in this area in recent years, some of them jarringly out of character with the neighborhood.

“You see some of these buildings, and you say, ‘What were they thinking?’ ” real estate broker Lynda Lipkin says.

To prevent more such development, a neighborhood group, the South of Foster Zoning Committee, is pushing for an RS-3 designation for the area.

“We are sad for the character and charm that we’re losing,” says Michele Walker, a member of the group.

Such feelings are understandable. But what the group proposes is a misuse of the zoning code, which is supposed to guide longterm development, not just stave off current threats.

Ald. Matt Martin (47th), whose ward includes this area, opposes the downzoning.

“People need to be careful what they wish for,” says former Ald. Ameya Pawar, Martin’s predecessor. “Zoning isn’t a cure-all for curbing NIMBYism or bad developer behavior. Zoning should be used as a framework so neighborhoods can be preserved, adapted or change over time.”

Still, most of the rest of Andersonville already has been downzoned. According to Steven Vance, founder of the Chicago Cityscape real estate information service, 56% of the 47th ward — which covers the largely affluent, densely built area from Andersonville to Roscoe Village — is zoned for single-family use.

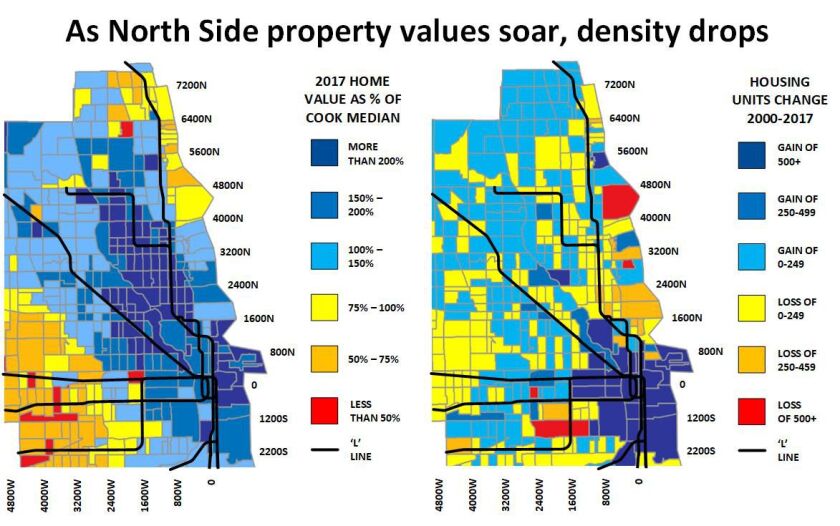

Downzoning is helping drive down North Side density and drive up the cost of housing. It’s part of a complicated problem that needs to be systematically addressed.

As the accompanying graphic shows, density loss is especially acute in neighborhoods near L lines. Most of these areas are — or were — heavily built up because they offer convenient access to downtown. In Andersonville and some other areas, that density supports a lively retail district.

These neighborhoods are attracting college-educated downtown workers, many who can afford to spend a good buck on housing. That’s given rise to deconversion — reconfiguring small apartments into fewer but larger ones, say turning a two-flat into a single-family home.

Developers buy and demolish older buildings and build new, larger and sometimes obnoxious structures. The inevitable backlash leads to downzoning.

But downzoning can’t prevent deconversion. Between 2000 and 2017, census data show, deconversions and teardowns have helped the North Side (from Lake Michigan to the Chicago River north of North Avenue) lose 6,600 dwellings in two-flat buildings — a drop of 28%.

Downzoning preserves existing affordable housing only to the extent that nobody deconverts and that nothing new is built. Artificially limiting the supply of new housing drives up costs. The average price of a new house on the mid-North Side — from Diversey Parkway/Avenue to Montrose Avenue, Western Avenue to roughly Broadway — now exceeds $1.6 million.

Few single-family homes have been built in Andersonville lately. But they’re expensive, with an average price of $1.3 million.

Keeping housing affordable is a fraught issue, with talk of greedy developers on one side, accusations of racism on the other. But it’s a conversation Chicago needs to have.

The 1966 comprehensive plan made no effort to change zoning. “There wasn’t the political will,” says Dennis Harder, a retired city planning department official.

We can’t afford to dodge the subject any longer. Density is what gives Chicago its buzz, attracting the well-educated younger people who are revitalizing the city. If density keeps dropping due to deconversion and shortsighted zoning decisions, the city’s future is in jeopardy.

Is it possible to build higher-density housing in desirable areas without destroying neighborhood character? Absolutely. Possibilities include:

- Allow “accessory dwelling units,” better known as coach houses and mother-in-law apartments. These could be incorporated into existing buildings with minimal impact on neighborhood appearance.

An amendment to the Chicago zoning code to allow these is in the works, says Vance, a supporter who thinks the idea will be popular with empty-nest homeowners looking for extra income to pay rising property taxes.

- Bring back the two-flat. A mainstay of Chicago’s affordable housing stock, two-flats originally were sold as a way for working-class families to afford home ownership — the rental unit helped cover the mortgage. Few are built now, as many prospective homeowners don’t want to be landlords.

But, with the price of a house in a middle-class city neighborhood increasingly out of reach, people might warm to the idea. The Chicago zoning code has a classification, RT-3.5, that seems designed to encourage two-flats. It’s little used other than in the Wrigleyville area but worth a closer look.

- Rezone for transit-oriented development. The city already allows this, but properties have to be individually rezoned, an arduous process. TOD projects have been built but not enough to move the density needle.

A better way might be selective upzoning of commercial streets near L stops — the closer to a station, the higher the density. Bonus density might be provided for projects offering a public benefit — say, affordable housing.

A good test case is the stretch of Broadway running past Andersonville — a drab commercial artery with many low-rise buildings surrounded by parking lots. One exception is a residential high-rise at Broadway and Winnemac Avenue with more than 700 units. It doesn’t look half bad, adding zip to a dull street. It’s also a short walk from the Argyle stop on the Red Line, which runs parallel to Broadway for two miles.

The city expects to spend billions in tax-increment-financing money rebuilding the Red Line. How better to generate more tax revenue than to strategically upzone the corridor the line serves?

We need to stop focusing on ad hoc responses to local problems and focus on citywide solutions. And, to do that, we need a plan.

This is part of the ongoing series City at the Crossroads by journalist Ed Zotti on trends affecting Chicago and choices the city faces.

Email comments to letters@suntimes.com.