On the North Side, Chicago public elementary schools are an increasingly popular choice for middle-class families.

On the West Side and South Side, though, parents are abandoning neighborhood schools. At dozens of schools, mostly in African American communities, enrollment has dropped so low that closing or consolidation seems inevitable.

Those are the takeaways from an analysis of CPS data showing a school system in the midst of profound change.

There’s reason for optimism. Thirty years ago, few middle-class parents in Chicago willingly sent kids to the neighborhood public school. Now, many do — an extraordinary turnaround for a school system once derided as the worst in the nation.

Elsewhere in the city, though, neighborhood schools are in unmistakable decline.

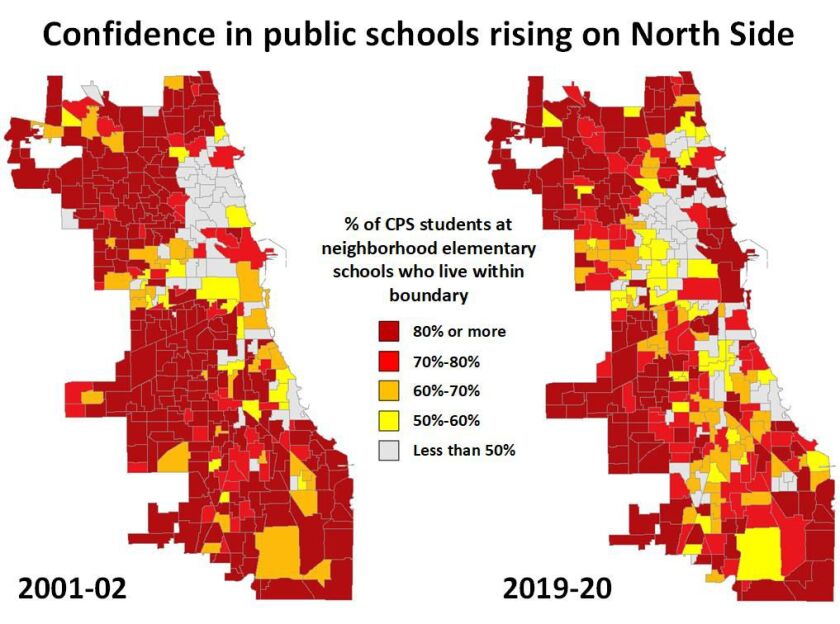

The accompanying maps, based on nearly 20 years of data, show the changes transforming the Chicago Public Schools. The maps reflect parents’ confidence in a particular school as demonstrated by whether they send their kids there.

The first set compares the percentage of students at neighborhood CPS schools who live within their school’s attendance boundary for the 2001-02 school year vs. 2019-20.

In 2001-02, CPS students in most parts of the city attended their neighborhood school.

The major exception was the north lakefront. At most public schools in this affluent area, fewer than half of the students lived in the neighborhood. The rest typically were minorities transferring from other parts of the city.

Clearly, many middle-class families along the north lakefront at the time sent their kids to private schools.

The situation is different today. At many neighborhood schools on the north lakefront, most students live nearby. At some, enrollment is much higher. Blaine School in Wrigleyville had 568 students in 2001-02 and has 815 now. Ogden School on the Near North Side went from 560 to 1,111.

How many kids in these neighborhoods attend private schools isn’t known. It’s fair to say a growing share of them, many from middle-class families, are going to CPS.

Some neighborhood school advocates say the impetus for this has been grassroots organizing, typically in the form of a “Friends of [local] School” group. An online search turns up more than 50 such groups devoted to CPS schools.

A common start for “Friends of…” groups is mothers taking their toddlers to a park and commiserating over the cost of private schools, then banding together to support the neighborhood school.

If the principal is willing, they volunteer, hold fundraisers and other events and give tours.

Gradually, they persuade more families to send their kids to the school. A sign that a school has turned the corner in parents’ eyes is when real estate agents start advertising “in [local] school district” in home listings.

Elaine Allensworth, director of the UChicago Consortium on School Research.

University of Chicago

“In the case of lakefront neighborhoods, it’s safe to say every single neighborhood school that changed to majority local attendance saw the formation of a ‘Friends of…’ group sometime in the last 20 years,” one school activist says.

Crediting “Friends of…” groups as chiefly responsible for the change in North Side schools is “a leap,” says Elaine Allensworth, director of the UChicago Consortium on School Research.

Among factors that Steve Tozer, founder of the Center for Urban Education Leadership at the University of Illinois at Chicago, cites are these:

- Better schools overall. “CPS is in the top 5% of the country in terms of school improvement,” Tozer says.

- Better principals. “Chicago has become nationally recognized for school leadership development,” hiring 300 principals in the past 20 years trained by programs like UIC’s.

- Local school councils — the elected boards at each CPS school. “LSCs give parents leverage to have impact because they can hire and fire the school principal.”

Some are troubled that attracting more neighborhood kids in an affluent community means the school becomes whiter, more middle-class, providing fewer opportunities for minorities.

Fair point, but few would deny that well-supported neighborhood schools are the ideal. By easing parents’ anxiety about their kids’ education, they help keep middle-class families in the city.

The North Side’s experience shows schools are a trailing indicator of neighborhood revival, not a leading one. Amenities and affordability might be what draw people to an area, but the emergence of a well-regarded public school is what keeps them there.

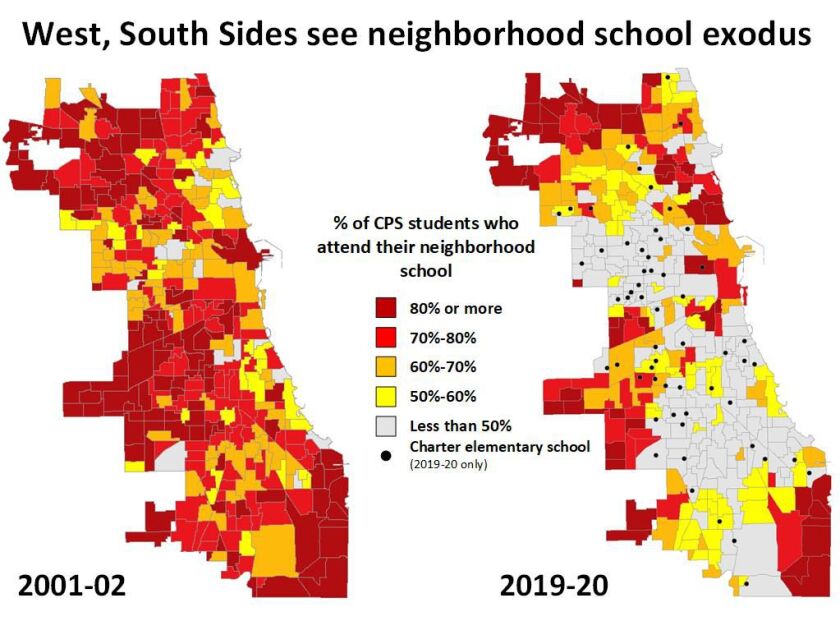

While neighborhood schools are enjoying a resurgence in some North Side communities, they’re fading elsewhere in the city. This is apparent in these maps.

They show the percentage of CPS students attending their neighborhood elementary school rather than an alternative, such as a magnet, selective-enrollment or charter school.

The change over two decades is startling. In 2001-02, most CPS students in all but a handful of communities attended neighborhood schools. Today, in large areas of the city, most don’t.

The major contributor to that clearly is charter schools. In 2000, Chicago had 15 charter schools; versus 118 today, 54 of them elementary schools.

Charter elementary school locations are shown on the 2019-20 map. Most are on the West Side and South Side, where the impact on neighborhood schools is most pronounced. But charter schools are associated with losses at nearby neighborhood schools almost everywhere.

How you feel about that depends on how you feel about charter schools.

“We’ve demonized the word choice,” says Ulric Shannon, director of external affairs for Civitas Education Partners, a charter network. “Well-off families have always had the choice of public or private schooling. For low-income families with children in underperforming neighborhood schools, charter schools were the first time they’ve had realistic alternatives.”

That might be, but research indicates that, on average, charter schools don’t outperform neighborhood schools.

And they put the city in an uncomfortable position. Often described as two cities — one rich and one poor — Chicago now sees that split reflected in its schools.

Prosperous areas are characterized by well-supported neighborhood schools — increasingly so on the North Side and along the central lakefront. In not-so-prosperous parts, neighborhood schools are withering away.

According to CPS data, 41 elementary schools, mostly on the West Side and South Side, have fewer than 250 students, making them candidates for closing or consolidation.

Well-supported neighborhood elementary schools historically have been the bedrock of stable communities. Charter schools, which draw citywide, don’t perform the same function.

You can’t blame parents for choosing charters — they’re trying to do right by their children. But something important is being lost.

Email comments to letters@suntimes.com.