But her story is hardly known. Not in Illinois, where — despite anti-slavery laws — she was born into bondage. Not in the downstate city of Pekin, where — despite anti-Black attitudes — she became a beloved community figure. And certainly not in Peoria, where — despite her impressive life — she is buried in ignominy.

Perhaps her story is more subtle than those of high-profile abolitionist leaders, yet her fortitude was astounding. Barely a teenager, she first stood up for her civil rights in a court that was stacked against Black people. Even amid legal defeats, she kept seeking the most basic of rights: freedom.

“She was a very impressive lady,” says Carl Adams, a historian who has spent more than a quarter century researching Legins-Costley.

She eventually won her freedom thanks to Abraham Lincoln — in 1841, long before he became president and more than 20 years before the Emancipation Proclamation.

That made Legins-Costley the first Black person freed by Lincoln. She would be followed by four million others.

Adams and other historians say her case pushed a previously ambivalent Lincoln toward an anti-slavery stance.

“This was the first time Abraham Lincoln first gave serious thought to these conditions of slavery,” Adams says.

Yet not only is her story relatively unknown, Legins-Costley’s final resting place isn’t even marked. Decades ago, the graveyard in Peoria where she was buried was paved over.

Legins-Costley lies somewhere amid a muffler shop, union hall and other commercial buildings in an asphalted-over tomb.

A free state’s slaves

Illinois, “Land of Lincoln,” once was the land of slavery. After losing the Revolutionary War, Britain ceded a vast chunk of land — including what would become Illinois — to the United States. Established in 1787, the Northwest Territory forbade slavery under the federal Northwest Ordinance. When Illinois became a state in 1818, its constitution prohibited slavery.

But legislation is one thing, reality another. In 1752, when France ruled the area, Black slaves were held by 40% of Illinois households, according to The Randolph Society, a historical organization in Randolph County in southern Illinois.

“It is a presumption of law, in the State of Illinois, that every person is free, without regard to color. ... The sale of a free person is illegal.” — Illinois Supreme Court ruling, 1841

Despite the Northwest Ordinance, the territorial government didn’t enforce the slavery prohibition. Nor did the state do so immediately after joining the union in 1818. What were known as “French slaves” — descendants of the area’s original slaves during the 1700s — continued to be held in subjugation into the mid-19th century. And slaves could legally be brought to Illinois from slave states for one-year — but renewable — work contracts.

The territory and state also allowed indentured servitude. The lengths of servitude varied by age but could extend as long as 99 years. Though the law implied the need for consent by the servant, the system was slavery by another name. Indentured-servitude contracts and the services of the servant could be sold like any sort of property, no consent necessary.

Amid this era of bondage came the arrival of a baby who would grow up to be Nance Legins-Costley.

Her story remained largely unknown until the mid-1990s, when Adams noticed a mention of her life. Adams, who had lived in North Pekin, gradually unpeeled layers of her life.

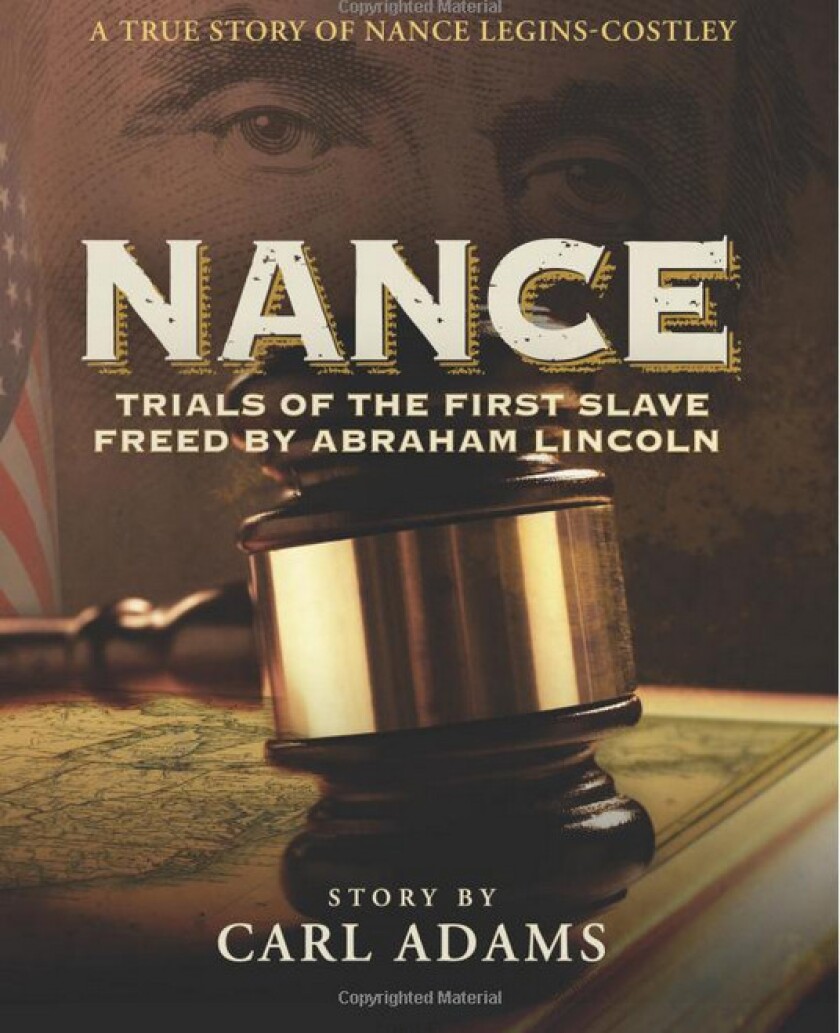

In 2016, Carl Adams published ”Nance: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln.”

Provided

“It is a short, simple story compared to most Lincoln books, but it has made a bigger impact than I ever imagined,” says Adams, who in 2016 published “Nance: Trials of the First Slave Freed by Abraham Lincoln.”

Nance was born in 1813 in Kaskaskia, which briefly was Illinois’ first capital. She likely was the daughter of Randall and Anachy Legins, who had been bought as indentured servants with two others by Col. Tom Cox for $770.

By law, Nance could be held or sold as an indentured servant until she was 28.

By 1820, Nance, 7, and her sister Dice, 5, were working at Cox’s Columbia Hotel. Though the capital had been moved to Vandalia, businessmen and other bigwig travelers would gather there and discuss issues of the day, including slavery.

And Nance, though illiterate for a lack of schooling, listened intently.

A Black girl’s boldness

In 1822, the Cox household — including indentured servants — moved to Springfield, which would not become the state capital until 1839. In 1827, with Cox awash in debt thanks to bad land speculation fueled by drunkenness, a Sangamon County court ordered the sale of his possessions, including his indentured servants.

In what amounted to the only legal slave auction in Illinois’ history, Dice was sold for $150 to a man named Taylor, and Nance was sold for a dollar more to Nathan Cromwell.

Dice went quietly. Nance did not.

“She did not want to leave the only household she ever had,” Adams says.

Nance resisted relocation with Cromwell, her stance remarkable for a Black girl not yet 14 years old. In return for her boldness, she was locked inside a windowless salt house for a week. After that, Cromwell forcibly took her from Springfield to his new home.

But Nance still had plenty of fight left.

Despite the court-ordered sale, Cox kept filing petitions to keep hold of his possessions, including his indentured servants. During a hearing in Sangamon County, Nance testified that, despite auction records that said otherwise, she had given no consent: “It is not true that I, Nance, voluntarily and of my own free will, agreed to go with Cromwell to his house . . . nor is it true I still live with Cromwell by my own choice.”

The case went to the Illinois Supreme Court, which ruled against Cox. But he kept up the fight with repeated appeals.

“Thomas Cox went to the Illinois Supreme Court more than anyone in history,” Adams says. “And he lost every time.”

So Nance remained with Cromwell. In 1829, he and his wife Ann Eliza took her along when they moved to Tazewell County, where they helped found a new city. Ann Eliza Cromwell gave the town its name, Pekin — the French spelling of the Chinese city Peking, thought at the time to be directly on the opposite side of the globe.

But after his wife died a couple of years later, Nathan Cromwell decided in 1836 to move to Texas, hoping to strike it rich in land speculation. Nance Legins, by now 23, objected to moving again: She already had a baby, with another on the way.

Cromwell had his own reasons to leave her behind. At 65, such a companion could spark scandal along the way to Texas, Adams says.

“Cromwell didn’t want to take a single, pregnant Black woman with him because it would attract attention,” the historian says.

A bargain for freedom

Cromwell approached David Bailey, a former business partner, suggesting that Nance stay behind and work at his store. Bailey was amenable. He was an abolitionist whose father-in-law had been a conductor on the Underground Railroad. He thought helping the young woman would be a step toward breaking her indentured servitude.

Also, as a result of a former business deal, Bailey owed Cromwell $400, Adams says.

Bailey agreed to sign a promissory note for that amount but only on the condition that Cromwell produce documentation of the young woman’s indentured servitude.

But Cromwell left for Texas without providing the paperwork. In St. Louis, far from his destination, he died. Immediately, Legins declared herself free, left Bailey’s service and lived independently.

On Oct. 15, 1840, in Pekin, she married a free Black man named Benjamin Costley. In addition to two girls, Amanda and Eliza Jane, the household would include a son born in 1841: William Henry Costley.

But Legins-Costley wasn’t yet free in the eyes of the law.

A relative of Cromwell went to court in Tazewell County, suing for Bailey’s $400 in the deal. Bailey argued he owed nothing: The sale had been nullified by the lack of the agreed-upon documents. When a judge disagreed and deemed Legins-Costley a possession, Bailey took the case to the Illinois Supreme Court.

For legal help, Bailey contacted an attorney friend with whom he had served in the Black Hawk War: Abraham Lincoln, 32, who was serving his fourth term in the Illinois Legislature.

His stance on slavery was ambivalent at the time, Adams says. He says Lincoln was wary of extreme abolitionists, some who’d burn flags and decry the constitution. Lincoln didn’t want to be seen as an anarchist.

“Burning flags did not go over well with veterans and others,” Adams says.

Still, Lincoln opposed slavery on principle. In addition to wanting to help his friend Bailey, he saw merit in the case, especially as it related to Legins-Costley’s long fight for freedom. She and Lincoln discussed the case, which ultimately pushed him toward a firm anti-slavery stance.

“It helped solidify Lincoln’s ideas about slavery,” Adams says.

On July 9, 1841, Lincoln appeared before the high court, his arguments leaning heavily on anti-slavery language of the Northwest Ordinance and the Illinois Constitution.

The justices agreed and ruled in favor of Bailey and Lincoln: “It is a presumption of law, in the State of Illinois, that every person is free, without regard to color. ... The sale of a free person is illegal.”

Legins-Costley was freed from indentured servitude, as were her children. So her infant son William Costley was the first male freed from bondage by Lincoln.

Legins-Costley and her husband remained in Pekin, where they had five more children. Though bereft of an education herself, she made sure all of them attended school.

The family lived in a log cabin along the Illinois River. Even before the high court’s ruling, she had become a valued member of the Pekin community. In the mid-1830s, Pekin got walloped by a triple whammy of cholera, malaria and scarlet fever. One of the first victims was the lone doctor, leaving medical care mostly to townsfolk. Despite having no medical training, Legins-Costley helped care for the ailing with little regard for her own safety.

“Nance was always willing to help,” Adams says.

She enjoyed that reputation the rest of her days in Pekin, says Jared Olar, a Pekin Public Library assistant who has written articles about Legins-Costley.

“Her reputation in Pekin was only one of praise,” Olar says. “Considering the prejudice against Black [people] there, they had respect for her.”

The 1870 Pekin city directory recognized Legins-Costley with an entry among notable citizens: “With the arrival of Major Cromwell ... came a slave. That slave still lives in Pekin and is now known, as she has been known for nearly half a century ... (as) ‘Black Nancy.’ She came here a chattel. ... But she has outlived the age of barbarism, and now, in her still vigorous old age, she sees her race disenthralled; the chains that bound them forever broken, their equality before the law everywhere recognized and her children enjoying the elective franchise.”

When he was around 23, William Costley left Pekin in 1864 to join the 29th Illinois Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops, the only Black regiment from Illinois and the largest of the state’s regiments. After battles elsewhere, the regiment was sent to Texas in June 1865. Though Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered April 9, Union troops never had invaded Texas, leaving 250,000 slaves there still unfreed.

On June 19, with Costley and his regiment among federal troops sent into Galveston, Gen. Gordon Granger announced, “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

A celebration followed, one that continues annually today on what is known as Juneteenth.

After the war, William Costley returned to Pekin. In 1870, he was at the center of another racially connected court case. On a Pekin street, a white convicted rapist was assaulting a woman. When the man refused Costley’s demand to stop, Costley shot him dead. Though charged with murder, Costley was acquitted by an all-white jury, which called his actions “justifiable homicide by protecting a woman in need.”

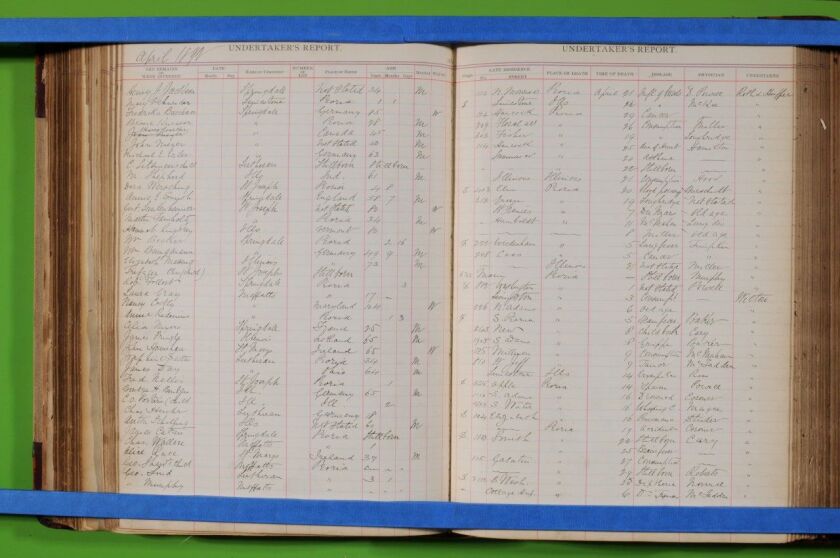

This 1892 undertaker’s report, by the Peoria Health Department, records the April 6 death of Nance Legins-Costley about half-way down the page on the left. The entry has several errors, among them her name being listed as “Nancy Costly.” Also, though she was born in Kaskaskia in 1813, the ledger lists her birthplace as Maryland and her age at death as 104.

Peoria Journal Star

He left for Iowa before moving to Minneapolis in the 1880s. In 1888, while still suffering shoulder pain from a shrapnel injury during the war, he was admitted to Rochester State Hospital in Rochester, Minn. He died there that same year.

In 1883, Legins-Costley’s husband Ben Costley died of unspecified injuries. After that, Legins-Costley went to live with daughter Amanda and her husband in Peoria. She died in Peoria at 79 on April 6, 1892.

‘How was she missed?’

As Adams discovered more and more about the story of Nance Legins-Costley, there was speculation about her burial. The mystery headed toward a solution in 2017, when amateur researcher Bob Hoffer of Peoria found the site of Moffatt Cemetery. While tracing family roots, he delved into records showing that the graveyard had thrived in the late 19th century. But, by 1905, the city shuttered the cemetery, possibly for overcrowding.

Abandoned, the site fell into disrepair and became almost unrecognizable. Later, the city announced plans to develop the area, promising to move the graves to other cemeteries.

“That was far from the truth,” Hoffer says. “It was absolutely criminal what happened.”

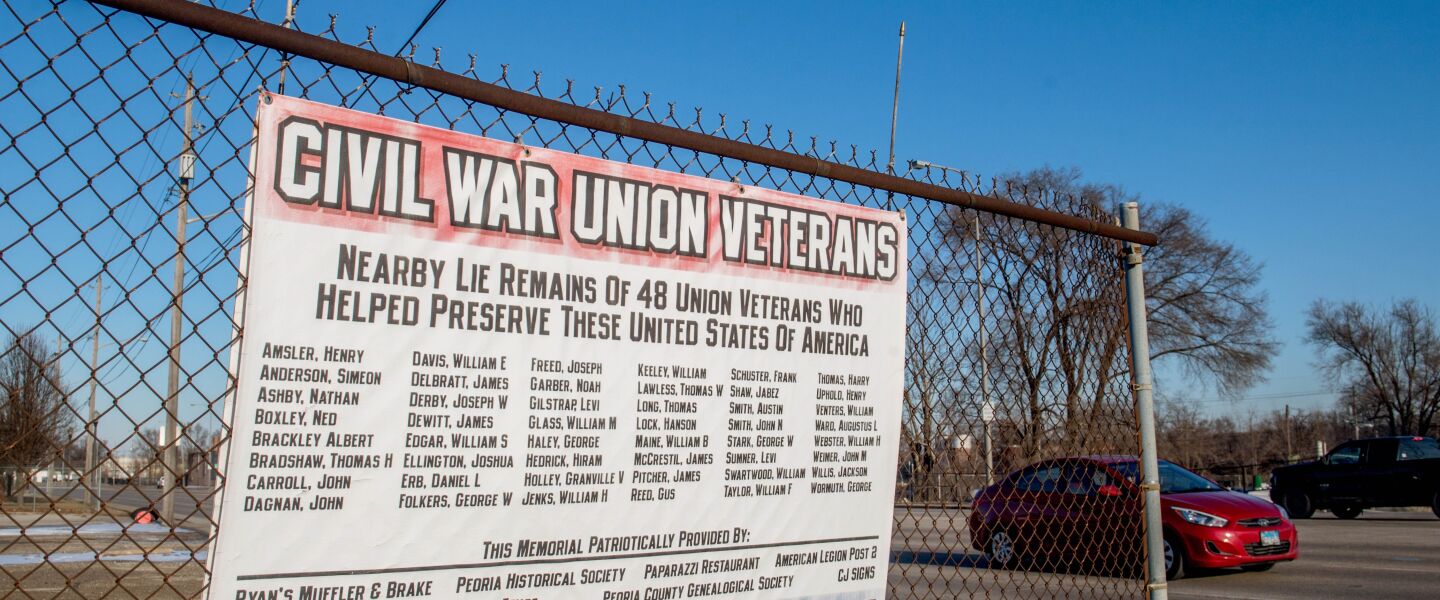

His research shows that maybe 100 graves were relocated. The rest — as many as 3,000, including those of 48 Union soldiers — were covered by asphalt. At a ceremony in 2017, Hoffer and others placed a sign on a fence to recognize the names of the soldiers buried there.

Noticing his work was Deb Clendenen, a retired nurse and genealogical researcher. Reviewing those records, she discovered that Legins-Costley had been buried in Moffatt Cemetery. But Hoffer says no records have been found to show that Legins-Costley was among the city’s few grave relocations. Her husband also is likely buried there.

Hoffer, Adams and others are working on plans to create a permanent marker to recognize Moffatt Cemetery and honor Legins-Costley.

Adams, 69 and living in Maryland, marvels at how long history bypassed her story.

He says, “How was this missed?”

Read more at usatoday.com