Emmett Till’s lynching ignited a civil rights movement. Historians say George Floyd’s death could do the same.

At protests held across the United States in recent weeks, many have invoked the name of Emmett Till to suggest the nation could be in the midst of a defining moment that could inspire societal shifts.

They say the degree of outrage, mobilization and attention spurred by the horrific, visceral recordings of the deaths of Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor could have a catalyzing effect similar to that of Till’s lynching, which shocked the world and gave birth to a generation of civil rights activists.

“These two tragedies showed the tipping point of society,” said Benjamin Saulsberry, museum director at the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, Mississippi. “The Emmett Till murder was not the first murder. There were so many others. But it was the tipping point.”

Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago, was lynched in August 1955 while visiting family in Money, Mississippi. After supposedly whistling at a white woman, Till was kidnapped by a group of white men who tortured and killed him. His body was discovered in the Tallahatchie River, with a 74-pound cotton gin fan barb-wired to his neck.

Two men were later acquitted on murder charges, and a grand jury declined to indict them on kidnapping charges.

Years later, the white woman involved in the incident said she lied when she said Till had touched her.

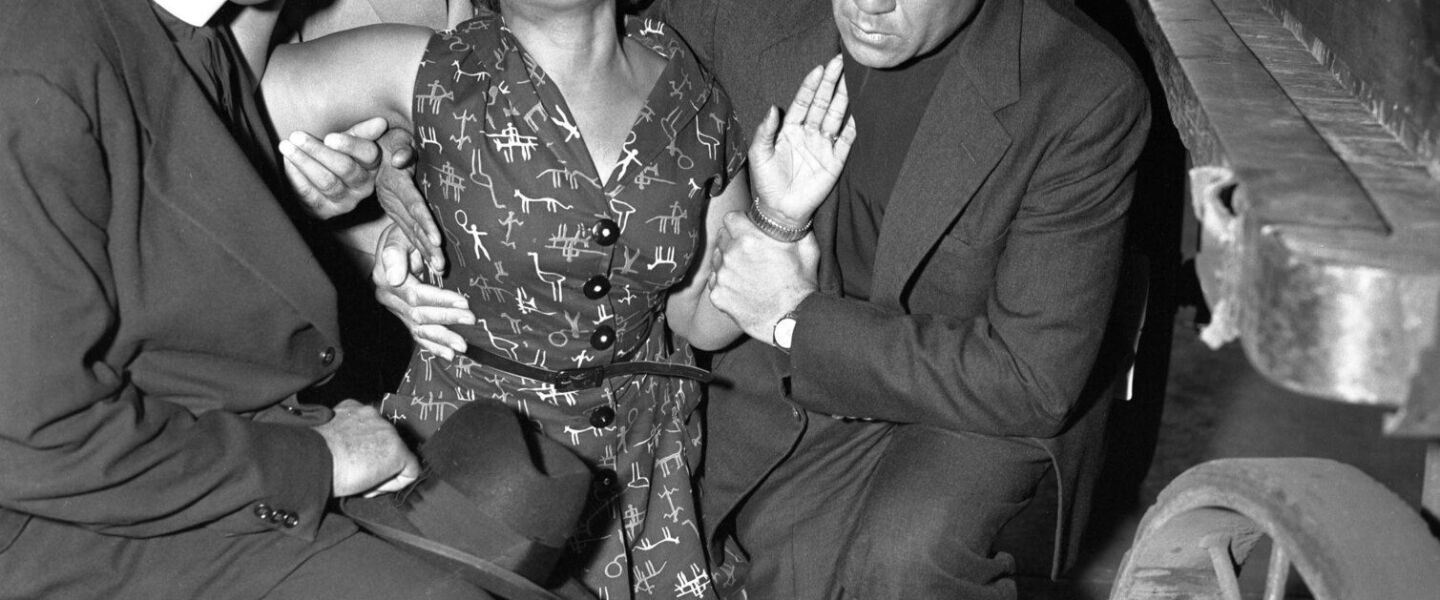

Mamie Till Mobley collapses as her son Emmett Till’s body arrives at Chicago’s old Illinois Central Railroad station after his murder by racists in Mississippi. On her left, with the white collar, is Alva Doris Roberts’ husband, Bishop Isaiah L. Roberts, who presided over the funeral. On the right, also dressed in clerical black, is Bishop Louis Henry Ford, who gave the eulogy for the slain teenager.

Sun-Times file

Till’s mother Mamie Till-Mobley forced the world to take a deeper look at racism in the United States when she decided to have a public, open-casket viewing, held on the South Side at Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ, 4021 S. State St. Over the course of four days, tens of thousands of people stood in line to view the murdered teenager’s body.

Till-Mobley also gave permission to the black press to photograph her son’s mutilated remains and circulate the images in black newspapers and magazines.

“Because his mother had the divine strength to choose to have an open-casket viewing, it forced America to see — for the first time — what American racism actually looked like,” Saulsberry said.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson later called Till’s murder the “big bang” of the Civil Rights Movement. Rosa Parks said Till was on her mind the day she wouldn’t give up her seat on that Montgomery bus.

His death drove a generation of Americans to launch sit-ins to end Jim Crow segregation and sparked a nine-year battle for the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

This isn’t the first time Till’s name — part of a long lineage of African Americans dying at the hands of police and vigilantes — has been invoked. It was heard on the streets of Los Angeles in 1992, when demonstrators protested the acquittal of four police officers accused of beating Rodney King, and in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, when people protested the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by a white police officer.

In recent weeks, protesters marching in response to the deaths of Floyd, Arbery and Taylor have chanted Till’s name.

Arbery, 25, was chased down and shot to death by three white men while jogging near his Georgia home in February.

Taylor, 26, was fatally shot by police in March after they entered her Louisville apartment during what they said was a narcotics investigation.

And Floyd, 46, died in Minneapolis on Memorial Day when, as video captured for an outraged nation, he was pinned to the ground by an officer after being accused of passing a fake $20 bill at a grocery store.

“George Floyd dying on TV with a knee on his neck was our Emmett Till moment where we see the brutality and the lack of humanity that we can literally not ignore any longer,” John Gray, pastor of Relentless Church in Greenville, South Carolina, told parishioners.

In Vanity Fair, W. Ralph Eubanks, author of “Ever is a Long Time: A Journey Into Mississippi’s Dark Past,” wrote: “There is a long bright line that connects Mamie Till-Mobley’s decision to let the world see her son’s battered body in the casket — images of which Jet magazine published — to the videos of police brutality we have been seeing on our screens, like the one of a Minneapolis police officer killing George Floyd.”

At a news conference last week in Minneapolis, attorney Ben Crump — a lawyer representing the families of Arbery, Taylor and Floyd — listed 20 African Americans who died in encounters with police and vigilantes and called on people to “take a breath for Emmett Till.”

The deaths of Till and Floyd, in particular, have been “points of clarity” in a much longer storyline, said Amy Yeboah, an assistant professor of Africana studies at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

“This has been a 400-year connect-the-dot picture,” Yeboah said. “Instances have all connected in some form or fashion in helping us understand the hurt and pain of black people.”

Both moments have been marked by the circulation of horrific images of death, said Brandon Marcell Erby, who studies the rhetorical work of Till-Mobley. Erby, who recently got a doctorate in English and African American and Diaspora Studies at Pennsylvania State University, sees a parallel in Till’s open casket and photos of Till’s body with the video evidence documenting the deaths of Arbery and Floyd.

“Now, with the videos, we see the exhibited corpse,” Erby said.

Keith Beauchamp, whose documentary “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till” helped move the Justice Department to reopen the Till case in 2004, said he could watch the video of Floyd’s final moments only once.

Keith Beauchamp, whose documentary “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till” helped move the Justice Department to reopen the Till case in 2004, says seeing the slain teenager’s photo drove him to pursue a life of civil rights work.

Sun-Times file

“I’ve seen death time and time again with the work I do,” Beauchamp said. “But nothing has ever hit me harder than the image of George Floyd. When I saw that image, it brought me back to when I first saw the photograph of Emmett Till at the age of 10.”

Beauchamp said seeing Till’s photo drove him to pursue a life of civil rights work.

“For many people now, it’s going to be that image of George Floyd being on the ground, suffocating — that’s going to be their inspiration to continue the work,” Beauchamp said. “When we see the face of George Floyd, it doesn’t take us far from the death of Emmett Till.”

There are parallels in the historical context of the two men’s deaths, said Christopher Benson, a journalist, lawyer and co-author with Till-Mobley on her book “Death of Innocence.” When Till boarded the train to Mississippi, he was headed to the Jim Crow-era South in the wake of the “Brown v. Board of Education” ruling, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ordered schools to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” In the weeks before Till’s murder, two black men were lynched in Mississippi.

“The death of Emmett Till was a reaction to a fear among white people in the South to change that resulted from the legal struggle for equality,” Benson said.

“And now we have a fear of change once again — the new demographic change on the horizon,” he said, referring to the growing percentage of nonwhite people living in the United States.

Reporters documented Till’s murder, open casket and trial (which Till-Mobley called a “farce”) in what then-West Point Daily Times Leader reporter and future New York Times correspondent and author David Halberstam later called the first “major media event of the civil rights era.”

Similarly, major news organizations have provided “wall-to-wall” coverage of the recent high-profile deaths, protests, legal development and memorials for Floyd, Benson said.

But there also are marked differences in the two moments, historians say. We’re living through a global pandemic that has disproportionately affected communities of color, and people are simultaneously fearful of gathering in large groups and “fed up” with structural racism, now laid bare by the outbreak, Saulsberry said.

There are more black elected officials today. There’s greater diversity in police departments — whose officers now face protests in full military gear, Yeboah said. Developments in technology have given rise to social media campaigns and the Black Lives Matter movement, while prompting questions about who conducts surveillance and controls images of black bodies.

“Miss Till gives permission for us to see her son,” Yeboah said. ”The Floyd family doesn’t have the power these days to give permission. Anyone who was in that space took their own footage and shared it.”

Some historians say it’s too early to speculate on the long-range impact of the current moment.

“This is perhaps our Emmett Till moment,” Beauchamp said. ”I only say ‘perhaps’ because we’re in the first phase of action — having the ability to protest. Now, after we’ve protested, what are the next moves?”

After 65 years, Till’s family is still waiting for justice. The Justice Department is investigating his death. And anti-lynching legislation in Till’s name, which passed the House in February, has stalled in Congress.

There’s reason for hope, Beauchamp said, because the current nationwide momentum feels “much bigger” and more pervasive than the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2013, more akin to the movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

“This is the time — the defining moment of our lives,” Beauchamp said. “And this will set a precedent for where we’ll be in the next 100 years.”

Contributing: Nathaniel Cary, Lily Altavena

Read more at USA Today.