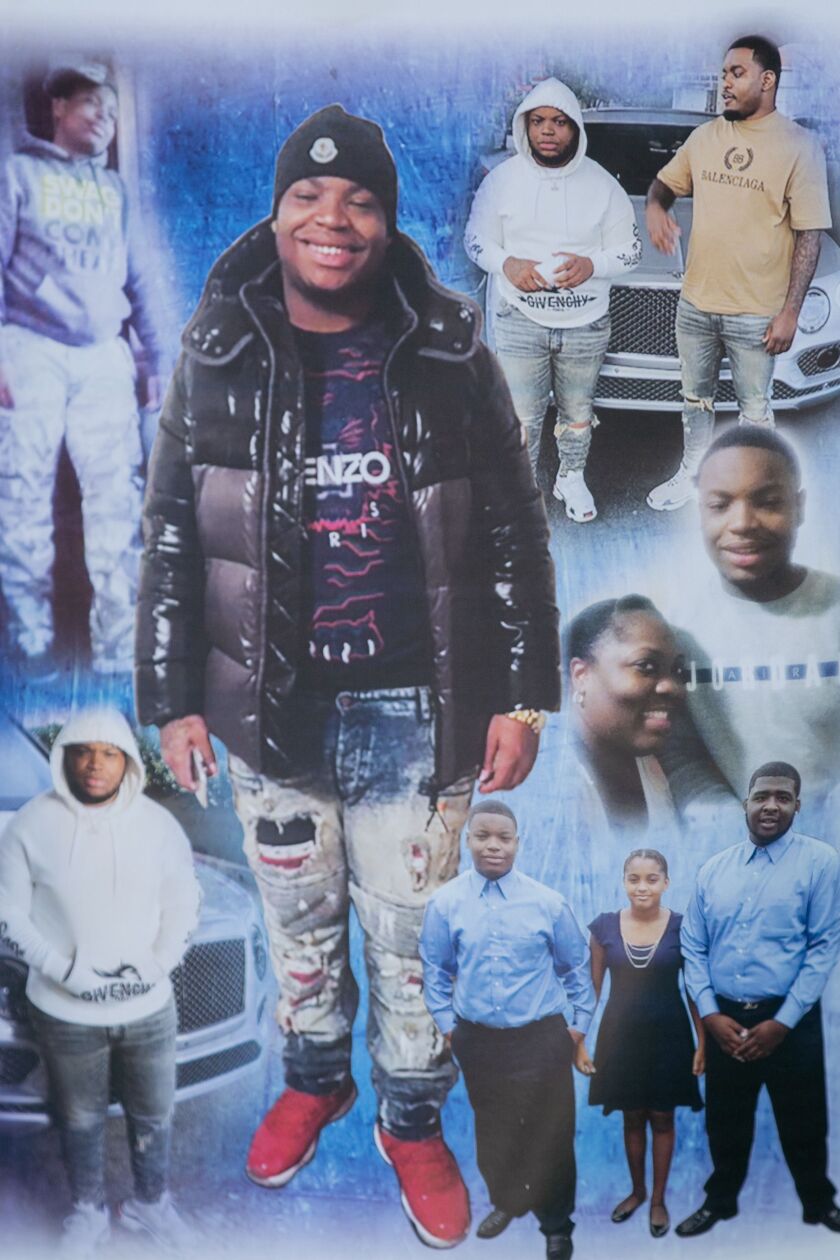

Malik Webber loved to eat. Chicken. Chitlins. Spaghetti. Dressing. He was social, with lots of friends, always a smile on his face.

These are the things Angie Graves remembers most about him. Graves, 48, knew Webber since he was a kid. He lived a few houses down from her on a North Lawndale block where everybody knows everybody, and kids line up to buy snow cones.

Webber died by suicide in March. He was 21.

“You still ask yourself why,” says Graves, who took in Webber when he was a teenager and calls him her son.

She doesn’t know why Webber killed himself. He didn’t leave a note.

“He struggled,” she says. “He probably was struggling for a long time.”

Midway through 2020, Cook County is seeing an alarming rise in the number of suicides among Black residents. The number of deaths already has matched all of last year and has this year on pace to be the worst in a decade.

As of July 24, the Cook County medical examiner’s office has recorded 57 deaths of Black men, women and children from suicide this year. That compares to 56 — which was a nine-year low — for all of 2019. Since 2010, the average number has been 65 a year.

Seven of the deaths this year, including Webber’s, occurred within a single two-mile radius in North Lawndale, an examination of data from the medical examiner’s office shows.

There hasn’t been a similar rise in suicides among white Cook County residents. Whites account for the majority of suicides here as well as nationally. Nor has there been a rise in suicide among Latinos, though the medical examiner’s data on ethnicity can be flawed.

Typically, the number of suicides falls during the summer and winter, but, among Black Cook County residents, the figure has doubled in the first half of 2020 compared to last year.

Also, the number of suicides among Black people under 30 midway through this year is nearly double the average for the same six-month period going back to 2010, according to the medical examiner’s data.

Lakeidra Chavis reports for The Trace, a nonprofit news organization covering gun violence in America.

It’s difficult to know the precise number of Black suicides for a variety of reasons. Among them: whether what appear to have been accidental drug overdoses actually were suicides.

The overall numbers of suicides in Illinois and nationwide have been rising over the past two decades, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rise in the number of Black Cook County residents taking their own lives this year began even before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the state’s stay-at-home order. Most of the victims were male. Just over 40% of the deaths involved a gun. About a third were hangings.

The median age at death was 36, according to the medical examiner’s data. But the youngest victim, a boy who died earlier this month, was only 9 years old.

The deaths overwhelmingly occurred in Chicago, often in South Side and West Side neighborhoods with high rates of unemployment and poverty — communities that also have disproportionately been hit by the pandemic in terms of the number of deaths and the resulting economic devastation.

There’s no single explanation for the rising number of suicides. But, according to the CDC, anxiety and depression are up among Black Americans in general amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a national reckoning over racism and how Black people disproportionately are victims of poverty and police abuse. Even before the pandemic, the numbers of shootings and opioid-related overdoses — both of which also disproportionately affect Black people in Chicago — were up this year.

The increase in Cook County could indicate an emerging crisis for Black Americans’ mental health during the pandemic, some researchers and people who work in the field say, but they caution that it’s too soon to know that for certain.

Arturo Carrillo, a clinical social worker in Chicago, says private and nonprofit health centers often have long wait lists, making them difficult to access for low-income residents.

“If you have health insurance, if you can pay out-of-pocket co-pays, and you live in more affluent parts of the city, you have a buffet of therapists to choose from,” says Carrillo, who leads the Collaborative for Community Wellness, a mental health organization. “If you live in low-income communities, you get the scraps.”

In a report earlier this month, Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s COVID-19 Recovery Task Force made recommendations for improving mental health services in Chicago that included offering mobile-service vans and establishing a “211” helpline just for mental health needs. The group did not call for bringing back the city’s six mental health clinics, which then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration closed in 2012.

Carrillo, who was part of the task force’s mental health focus group, has criticized Lightfoot for not reopening the clinics despite a campaign promise to do so. Chicago has five city-operated mental health clinics.

“Ignoring the issue until it becomes a crisis has become the method of treatment,” Carrillo says, “creating a city of waiting rooms.”

According to a study released by the task force, behavioral health hospitalizations among Black residents are higher than for other groups, and most of those hospitalizations are among people with significant economic hardship. The task force also noted that people on the South Side and the West Side have limited access to mental health clinicians.

“The going idea is that people do not seek services because of stigma, and we did some surveys [and found] that people are not getting services because of structural barriers,” says Amika Tendaji, a mental health organizer for the advocacy group Southside Together Organizing for Power. “They cannot pay the privatized services that have yearlong waiting lists.”

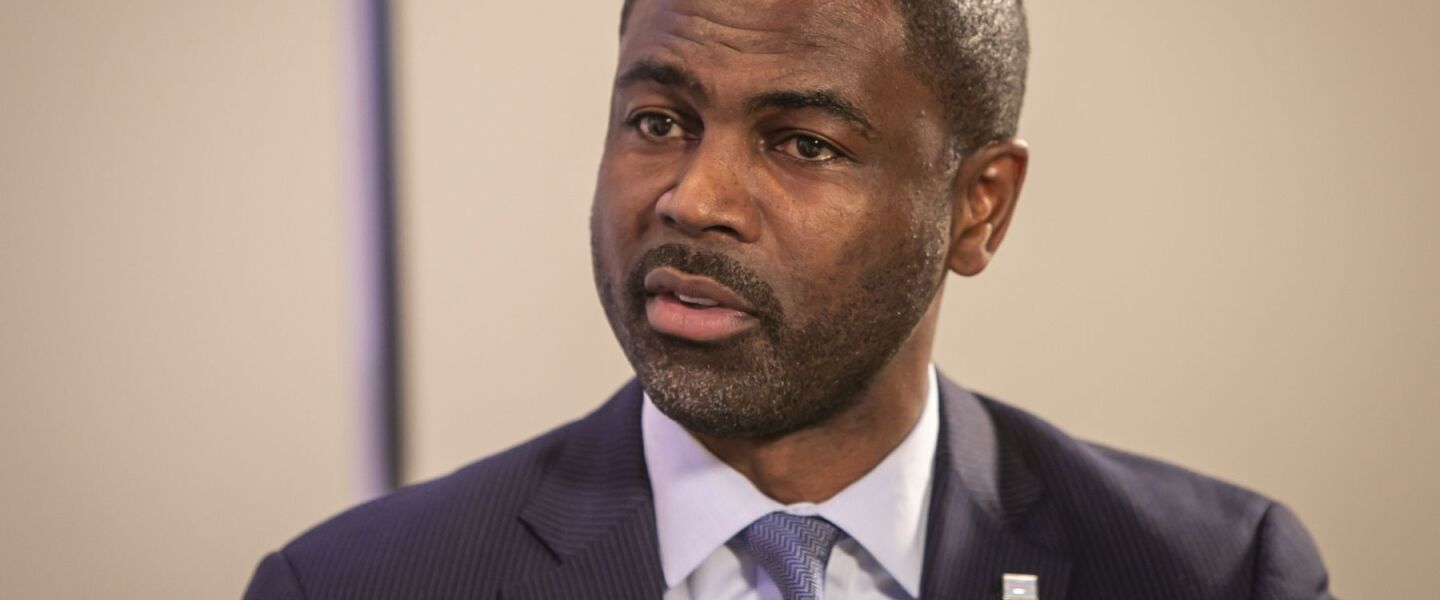

“We’re very, very concerned about any provisional data that there are disparities,” says Matt Richards, a deputy commissioner in the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Richards says the city agency plans in coming weeks to put out a public health alert in response to the rise in suicides and will seek proposals next month to offer new mental health services in communities most in need.

A report released earlier this year by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration said Black and Latino people have “substantially” less access to mental health treatment.

“We have to recognize that we have a problem and deficit as it relates to mental health support in our communities with high trauma,” says state Rep. LaShawn Ford, D-Chicago, whose legislative district includes the West Side. “These Black communities have been dealing with all the things poverty creates: violence, poor mental and physical health, drug use, suicide.

“Even before the pandemic, we were already dealing with a violent society suffering from major mental health conditions,” says Ford, who has asked a group of community leaders and mental health professionals to help identify ways to address the heightened level of trauma people on the West Side are experiencing. “And that kind of stuff really just got sidetracked. It seemed like the government could only focus on one thing at a time.”

Mental health professionals and clergy in Chicago say they are seeing an increase in anxiety and depression among their Black clients and parishioners.

“Within the first month of George Floyd happening, that conversation became very front and center,” says Matt Lawson, a counselor at Chicago Compass Counseling. “That conversation has led into a lot of other things that speak to some unspoken trauma. A lot of people in the Black community deal with this sense that we kind of carry around a burden or a sense that there’s something out there trying to get us.”

Sherry Molock, an associate professor of clinical psychology at George Washington University, says that with the pandemic and financial insecurity caused by the ravaged economy: “We’re all watching this, getting scared. In the Black community, [suicide] was already increasing a bit. And this is like another layer of stress.”

Sean Joe, a professor of social work who focuses on Black suicidology at Washington University in St. Louis, says it will take a few years to know the full impact of the stresses on Black communities.

“People are so preoccupied now,” Joe says, “that the emotional trauma they’re experiencing is kind of blunted.

“That wave is coming. It’s just too much unattended grief that’s happening.”

Contributing: Daniel Nass, Chip Brownlee