The Rev. Michael Pfleger has to think a moment to figure out how long he’s been the pastor at St. Sabina Church, which turned 100 this year.

“It’s 35 years. Wow. A long time,” Pfleger, 66, says laughing. “It’s funny, because in 1981, I was intending to leave.”

Pfleger arrived at St. Sabina as assistant pastor in 1975. He was 26.

“The top floor of the school and the basement of the gym building were closed. The basement of the church, all chained up. The pastor said the cardinal told him we were going to close, it was just a matter of maintaining,” Pfleger says.

MORE TO THE STORY: St. Sabina history: From Irish to black, closure list to thriving

“I was getting very frustrated. I wasn’t interested in maintaining. I’ve never told anyone this: I was going to take a leave of absence after Christmas 1980 and leave. I signed a lease on an apartment. In November, the pastor had a massive heart attack and died,” he recalls.

The black congregation, by then enamored of this audacious young white priest not satisfied with business as usual, wanted him as their pastor. There were two major problems with that.

“I was too young, and Cardinal [John] Cody couldn’t stand me,” Pfleger says.

However, bucking the system is in Pfleger’s DNA. His congregation clamored. Cody named Pfleger “permanent administrator.” When Cody died in 1982, then-Archbishop Joseph Bernardin appointed Pfleger the archdiocese’s youngest pastor ever.

“One of the first things I did was stop bingo immediately and Las Vegas nights. I said we’re just going to base this church on God’s word, and believe that if we are just serving God and the people, God will bless us, and we won’t have to spend so much energy fundraising. We refocused the church,” he says.

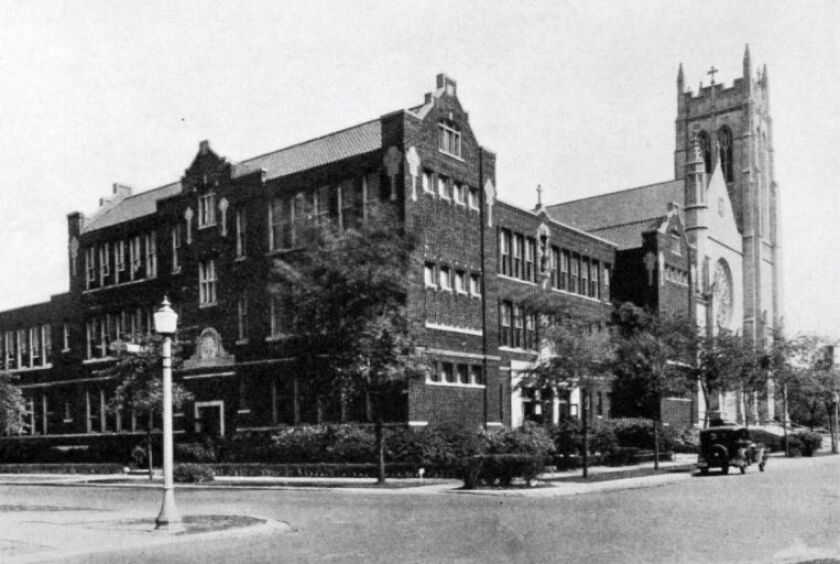

His own story is irrevocably woven into the history of St. Sabina, established July 9, 1916, in a storefront in an Irish Catholic enclave. By the early 1930s, the current church at 1210 W. 78th had been built. By the 1960s, after segregation battles and white flight, the neighborhood was all black.

“Another thing I did was begin infiltrating everything with African culture. It was a European church. There was nothing that made you think it was black Catholic,” he says. So St. Sabina’s sanctuary is imbued with African motif, as are Pfleger’s Sunday liturgies and rousing music that draw visitors from far and wide.

The activist priest rose to international fame raising a shrill voice on behalf of his church and its Auburn-Gresham community on the urban challenges of poverty, gangs and drugs.

St. Sabina’s story at 100 years is one of an urban church fervently embracing a social justice mission, an intensely active congregation recognized nationally for breaking the within-the-church-walls mold before such activism was considered the norm.

GalleryIts expansive campus includes Samaritan House, a 12-unit building for homeless; Elders Village, an 80-unit housing for elderly; a social service agency and a full-service employment center.

“It started with town hall meetings, asking the community what are the needs of the neighborhood,” Pfleger says. “I raised money from members, then asked a Republican and a Democrat, [former Illinois Attorney General] Jim Ryan and [former Mayor] Rich Daley, to donate toward an employment center. They did, and we opened up a little storefront off 79th & Racine.”

St. Sabina Academy is the largest black Catholic school in the archdiocese, with graduates including singer Chaka Khan and actress T’Keyah Crystal Keymáh. The community center, Ark of St. Sabina, offers myriad youth programs free, from computers to culinary; dance and music, a recording studio.

“If you look at the 10 communities in this city where violence is happening, you’ll find consistently, double-digit unemployment and poverty, underfunded and underperforming schools, lack of economic development or options for young people,” says Pfleger. “So my emphasis has been to fight the symptoms and causes of the violence.”

Beloved Community, Inc., a community development arm, helped bring new businesses like BJ’s Market, Walgreen’s and LaSalle Bank to its 79th Street corridor. The 2,500-member congregation funded the building of an HIV-AIDS clinic in Ghana in 2001.

Pfleger has over the years drawn headlines for unconventional methods of battling such ills as prostitution; the selling of liquor to minors, and spoiled food and drug paraphernalia at corner stores. St. Sabina even picketed the Jerry Springer Show for degrading women. Inside the church hierarchy, Pfleger clashed repeatedly with Cardinal Francis George, with George suspending him for disobedience. George had frequently indicated he would remove Pfleger from the parish but always backed down.

Today, gangs and gun violence are at the forefront for St. Sabina. Members have suffered high-profile losses of children to violence, including Blair Holt, 16, who was shot on a bus in 2007, and Tyshawn Lee, 9, shot in an alley last year.

“Two funerals that stand out in my mind were Tyshawn, a child executed. The other was a guy that at one point put a hit out on me and a few years later came and asked me for help. He was turning his life around when killed,” Pfleger says.

Every Friday night during summer months, his congregation marches against violence, and the church and its pastor were chief supporters of Spike Lee’s controversial “Chi-Raq” movie, with portions filmed at St. Sabina. The church also drew a national spotlight with its Community Peacemaker Program, corralling dueling gang members into basketball leagues with the carrots of GEDs and jobs.

“In the last 12 to 15 years, that’s been my primary focus — the violence and the brothers in the community who I believe society has left as throwaways,” says Pfleger, whose own foster son, Jarvis Franklin, was killed by stray gunfire on May 30, 1998.

He also had two adopted sons, one of who died of sudden illness in 2012.

Looking back, what’s he most proud of?

That a church once slated for closure is now vibrant, thriving, says Pfleger.

Archdiocese policy calls for priests to retire at age 70. Has he started thinking about retirement and passing off St. Sabina to a new shepherd?

“If I’m asked to retire, I will retire,” he says. “But retirement in general. No. I don’t know what the future will bring, but I believe you gotta die with your boots on, working.”

RELATED STORY: St. Sabina history: From Irish to black, closure list to thriving