By Chuck Neubauer and Sandy Bergo

Of Illinois’ 10 casinos, none is as lucrative as Rivers Casino in Des Plaines. Since 2012, it’s reported revenues of more than $400 million a year after winnings — twice as much as any other casino in Illinois.

That success makes its property quite valuable, according to Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios.

But, year after year, Rivers’ owners have argued that profits shouldn’t matter when calculating how much the casino is worth. And each year they’ve gotten an appeals panel to override Berrios, giving them more than $4 million in property-tax cuts since the casino opened nearly five years ago.

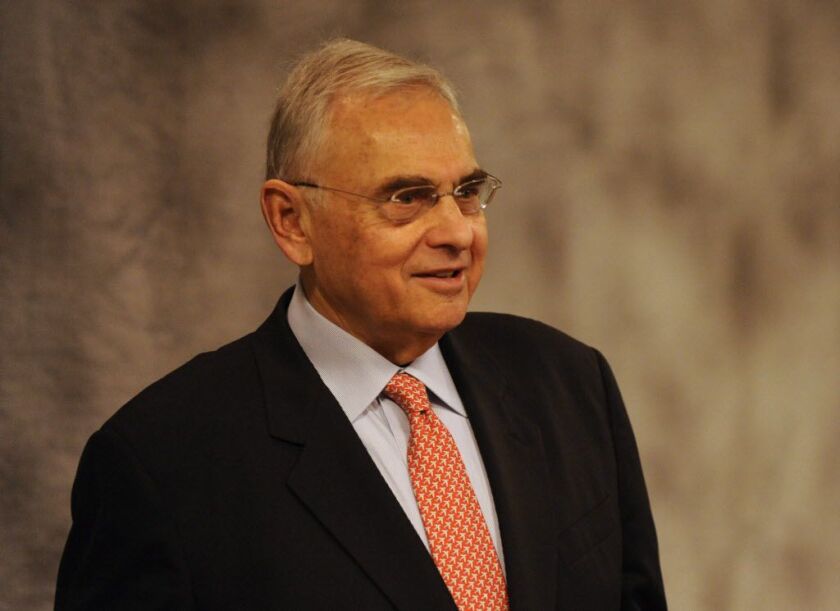

Figuring the value of the casino property should be “based upon what this property would be worth if we weren’t operating a casino there,” says Neil Bluhm, the politically active billionaire real estate developer who chairs the casino’s owner, Midwest Gaming & Entertainment.

Nor should the value be what Midwest Gaming paid to buy and build on the Rivers property along River Road north of Devon Avenue, Bluhm and his business partners argue. According to them, the property has declined in value and is worth tens of millions of dollars less than it cost them to buy and build on it.

They paid $117 million to buy the land and build the casino, according to records they provided to Cook County government officials.

But they’ve argued that the value of the casino and its parking garage is worth no more than $80 million. Most recently, they put the figure at $62.9 million — about 54 percent of what they spent on it.

Berrios’ office disagrees. The assessor has pegged the “fair-market value” of Rivers’ property at about $104 million each of the past four years.

But, as every property owner is entitled to do, Midwest Gaming & Entertainment has appealed every year, asking the Cook County Board of Review to override Berrios.

And every year it has. The agency — run by three elected officials who hear appeals of property assessments, which are used to calculate property taxes — has consistently cut the estimated value of the Rivers property to $88 million. That’s resulted in savings of $1 million a year on property taxes for the casino’s owners, records show.

Last year, Rivers paid $6.5 million in property taxes, money that went to school systems and other taxing bodies.

But, arguing that the Board of Review still overvalued the property, the casino’s owners have gone to court, suing to seek refunds of taxes they paid for three previous years.

When Rivers — or any other property owner — gets a cut in its assessment, other property owners have to make up for the loss in taxes to fund public schools, parks and other government functions. Similarly, if the casino’s owners prevail in their ongoing court appeals, taxing bodies would have to issue refunds and figure out how to make up that loss elsewhere.

Bluhm and his family also own or operate casinos in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Niagara Falls, Ontario. Bluhm’s group also is building a casino in Schenectady, N.Y., scheduled to open in 2017. Late last month, the Massachusetts Gaming Commission rejected Bluhm’s proposal to put a $677 million casino in Brockton, Mass.

Bluhm has been politically active, most notably as a “bundler” who helped President Barack Obama raise money for both of his runs for the White House. Bluhm hasn’t made any campaign contributions to Cook County officials who handle property assessments, though his tax lawyers and appraisal firm have.

Since 2011, Bluhm tax lawyer Terry Newman, Newman’s law firm Katten Muchin Rosenman and Madison Appraisal gave a total of $16,750 to Board of Review Commissioner Larry Rogers Jr., $15,150 to Commissioner Michael Cabonargi and $6,750 to Commissioner Dan Patlak. Newman, the law firm and Madison contributed a total of $31,700 to Berrios — who chairs the Cook County Democratic Party — and his personal political organizations.

Berrios’ spokesman says the contributions play no role in the assessor’s decisions: “That is clearly shown by the consistency of [the assessor’s] valuation figures of this property and the integrity of the proven and impartial methods used by this office.”

Newman, his firm and Madison Appraisal couldn’t be reached or declined to comment.

After years of reviewing potential owners and sites for Cook County’s first casino, the Illinois Gaming Board in 2008 selected Bluhm’s company and Des Plaines.

One of the lenders bankrolling the project called the Des Plaines location “superior,” being just across the street from Rosemont and only a mile from O’Hare Airport, with easy highway access.

Rivers’ revenues have exceeded expectations since it opened in July 2011. Based on corporate records, the owners already have recouped their original $150 million investment and paid themselves more than $300 million.

“Obviously, it’s been a successful investment, I’m not going to BS you,” says Bluhm, who points out that the casino also pays the state of Illinois $180 million a year in gaming taxes.

Before the casino opened, Thomas Jaconetty — the deputy Cook County assessor for valuation and appeals — says he gathered information about casino assessments from professional groups and seminars and from court decisions around the country. Jaconetty says he didn’t consider the property “unique.” Rather, he says he saw parallels with valuations of other commercial properties — like racetracks and hotels.

Assessments of commercial properties differ from single-family home assessments in several ways, chief among them that they produce income, which the assessor’s staff says is key to determining their worth. Assessors typically consider three key factors in deciding the value of commercial properties, experts say — income, comparable sales and the cost of construction and land.

With Rivers Casino, there were no comparable sales of casinos, so Jaconetty says he evaluated the income and cost, placing greater weight on income as the strongest measure of what a property would be worth in the eyes of a potential buyer.

Starting with 2012, the assessor’s office pegged the value of Rivers around $104 million, and the casino’s owners appealed, arguing that the money the casino brings in shouldn’t be considered in making the assessment.

“Their position is: It is not relevant, and we shouldn’t be looking at it,” Jaconetty says.

Each year, the Board of Review reduced the estimated value of the property to $88 million. And the following year, the assessor again put the value at around $104 million, leading again to appeals and cuts by the Board of Review.

The casino’s owners and their appraisers argued the property should have been valued at $80 million in 2014 and $62.9 million in 2015.

Pointing to that latest appraisal, Jaconetty questions how the casino could drop in value by 21 percent when gross receipts rose to $425 million that year from $418 million.

The Board of Review, though, calls the casino a “one-of-a-kind property” and says its commissioners based their most recent decision only on the owners’ appraisal and not on revenues.

The Rivers appraisals started with the original $117 million cost — $34 million for the land and $83 million for construction — and then deducted from that several factors. Among them: Rivers owners claimed the land was really worth only half what they paid, saying it was inflated because land owners knew of plans for a casino and jacked up their prices.

They also argued for deductions for the cost of an underground pond to comply with a state law that says casinos must be on water, the cost of upgraded interior finishes and physical deterioration.

Jaconetty says the rate of deterioration Rivers claimed was “a bit aggressive” and that the other costs were business decisions or factors inherent in opening a casino in Illinois, none of them warranting a lower assessment.

He also questions how spending more on the interior merits a cut in the value of the property.

“Looking good and being a classy place enhances your ability to draw customers,” Jaconetty says. “One could easily argue that enhances your value.”

Rivers also cited the possibility of future competition from a Chicago casino as a reason its assessment, and taxes, should be lower.

“My reaction was: We were not allowed to value on speculation,” Jaconetty says.

The next-most profitable casino in Illinois is Harrah’s Joliet, which paid about $3.1 million last year for 2014 property taxes on its hotel, restaurants and parking garages, records show.

It and the three other Chicago-area casinos all pay less in property taxes than Rivers in large part because they are on riverboats. Boats are considered personal property in Illinois and aren’t taxable as real estate. Those owners still pay real estate taxes on adjacent properties they own — parking garages, hotels and restaurants.

Chuck Neubauer and Sandy Bergo are Better Government Association investigators.