George Dante Jr. stands with a gloved hand resting on the backside of a bull elephant, aiming a flashlight at a place unaccustomed to light.

A few minutes later, a tiny video camera mounted on the end of a wire disappears inside the animal, on a journey, Dante hopes, to reveal a hint of the magic of a man who risked his life — and sanity — again and again in pursuit of perfection.

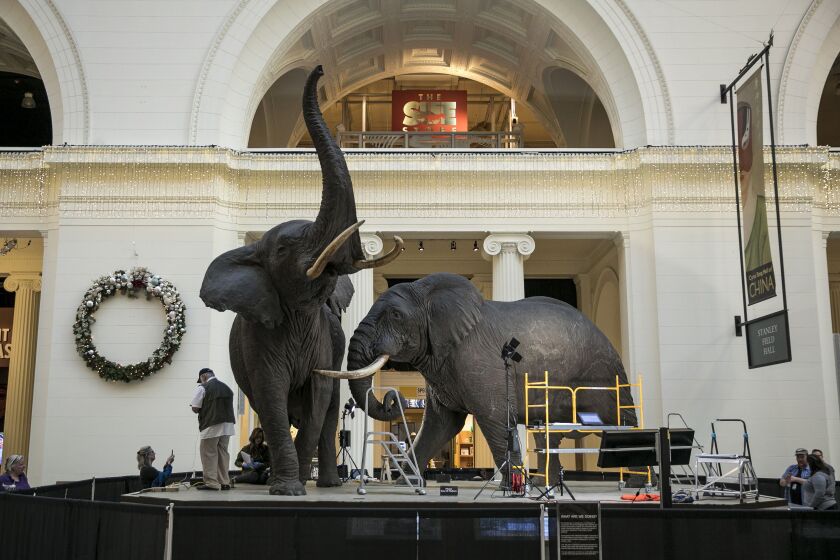

Dante compared working with the Field Museum’s famed “Fighting African Elephants” last week to being asked to restore Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling.

“It’s one the highest honors that could ever be bestowed on someone like myself,” says Dante, one of the nation’s premier taxidermists.

Dante, 43, is talking about Carl Akeley, a legend in the world of taxidermy — both for his pioneering skills in the field and his Captain Ahab-like pursuit of perfect specimens. In 1910, he leaped onto the head of a charging African elephant he’d been trying to capture. And he famously strangled a leopard leaping at him out of the grass.

But look closely at the pair of elephants Akeley and his wife, Delia, collected in 1906, and you’ll see cracks — ranging in length from one centimeter to 150 centimeters or longer — wandering across their thick, crinkly hides.

What’s happening to the elephants is something afflicting many of the museum’s hundreds of on-display mammals, some of which arrived from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Blame fluctuations in humidity and also bright light, among other things.

“A lot of these are masterpieces of animal sculpture in their own right and so in that sense they are irreplaceable,” said Larry Heaney, the museum’s Negaunee Curator of Mammals. “Also, we would not go out and shoot more of them at this point.”

Subdued lighting and glass cases have offered some protection. But the elephants have had it worse — exposed to the cold, dry air in the winter that blows in with the public, as well as the moist, hot air of summer.

The elephant skins are gradually stretching to the point of breaking. Hence Dante and his team’s arrival last week to make recommendations for repairs.

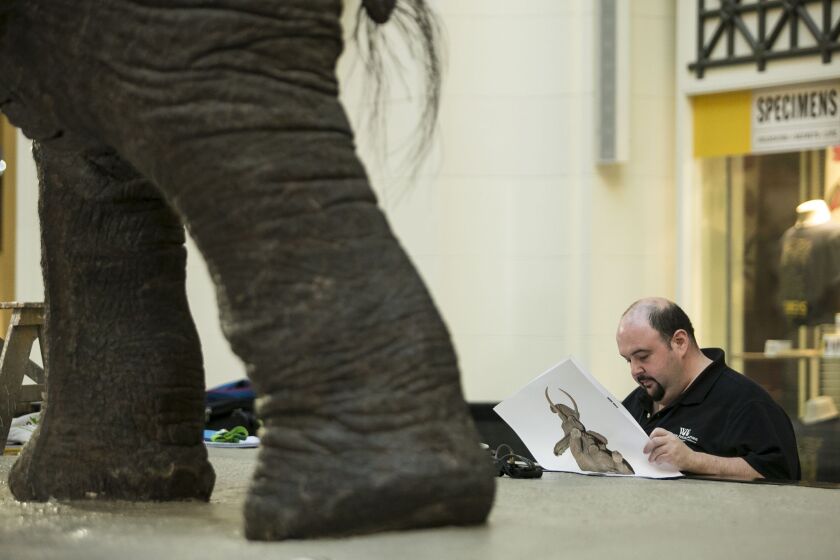

Amid the echo of children’s chatter in Stanley Field Hall, Dante could be found last week pressing a tailor’s tape measure up against the mud-brown hides, measuring cracks, while another member of the team took dictation on a laptop computer.

To the untrained eye, the elephants are perhaps regal creatures posed in thrilling combat, or maybe a sad reminder of a time when they were more plentiful in the wild.

Dante points to the way the elephants’ many wrinkles fold over each other. Akeley developed a sort of early Botox, injecting stucco into the elephants to plump up the skin, which was stretched over a form built from iron and wood, covered in wire mesh, then coated in plaster. Akeley was careful to angle the attacking elephant’s eyes so that they’re laser focused on its opponent.

“Akeley was a very accomplished sculptor,” Dante explains. “He knew animal anatomy. He knew animal behavior. When you look at these elephants, they convey the essence of a live animal.”

Akeley’s work had an “air of sorcery” in his day, says Jay Kirk, author of the 2010 Akeley biography, “Kingdom Under Glass: A Tale of Obsession, Adventure and One Man’s Quest to Preserve the World’s Greatest Animals.”

He made five trips to Africa, scouring the continent in search of perfect specimens to bring back to America. In 1910, while tracking a massive bull elephant atop Africa’s Mt. Kenya, the creature exploded out of a bamboo grove toward him.

“And then he had done the unimaginable. He had thrown the rifle aside, and actually reached out to grab hold of the tusk as it lanced passed him with the force of a sharpened, swinging log — a completely mad thing to do,” Kirk writes.

The elephant crushed Akeley’s chest, tore open his right cheek and “crudely scalped him,” according to Kirk. But Akeley recovered, spending three months on a cot in a safari tent with his wife treating his wounds. And then he went back to work.

Oddly, perhaps, Akeley and his museum bosses back in America saw themselves as conservationists, says Kirk. They believed their taxidermy — with wildlife photography still in its infancy — would help preserve species that were already on the verge of extinction thanks to the Europeans’ insatiable appetite for trophies.

On the surface, there’s nothing of the brooding obsessive in Dante. Not entirely true, says the man who, at 7 years old, mounted his first specimen: a tiny “spot” fish from New Jersey’s Barnegat Bay.

“I will push myself to the very limits. I’ve said on many occasions that I’ve spilled my blood, sweat and tears on my studio floor,” he says.

At any one time, he and his team are working on 200 to 400 specimens in his 4,000-square-foot shop in Woodland Park, New Jersey.

His handiwork — both original and restorative — can be seen everywhere from major museums to zoos and even a casino. His clients have included Bill Gates and Donald Trump Jr., according to Dante’s website.

He’s worked on mice and bears. He once spent two years — off and on — restoring a 35-foot-long whale shark. When he was asked to mount “Lonesome George,” an iconic tortoise from the Galapagos Islands that died in 2012, he interviewed people who’d known the animal to learn more about its “personality.”

“Because the last thing you want to do … is put it in a position and have someone look at it and say: ‘Well, it never did that. He never held his head that way, or he never moved his legs in this position,’” Dante says.

For Dante, working on the Akeley elephants is a defining moment in his career, he says. And, actually, for now, he has been hired only to assess the damage and come up with a plan.

“Every day, I have to pinch myself. Then I have to slap myself because I just can’t believe the opportunities we’ve had,” he says.

Dante estimates that, between them, the elephants’ hides are cracked in “hundreds” of places. Filling those cracks with resins and removing damaged or disintegrating “fills” is likely to take several weeks — at the very least, he says.

If he’s hired to make the repairs, the idea is restore the elephants to their original splendor, while keeping his own fingerprints to a minimum.

Having spent a week with Akeley’s elephants, Dante says his flashlight and careful eye have been unable to detect any mistakes by the master.

“He mounted one elephant in his life before he mounted these two,” Dante says, dwarfed by the behemoths. “This is the second and third elephant he’s ever mounted. This is a monumental task, and these elephants are better than most of the elephants that were ever done after him.”