MIAMI — H. Wayne Huizenga — a college dropout from Chicago’s suburbs who built a business empire that included Blockbuster Entertainment, AutoNation and three Miami professional sports franchises — has died at 80.

Valerie Hinkell, a longtime assistant to Huizenga (pronounced HY’-zing-ah), said Friday that he died Thursday night at his South Florida home. She gave no details on the cause of death, but The Miami Herald reported he’d been battling cancer.

Starting with a single garbage truck in 1968, Huizenga, who was born in Evergreen Park, built Waste Management Inc. into a Fortune 500 company. He bought independent sanitation engineering companies, and by the time he took the company public in 1972, had completed the acquisition of 133 small-time haulers. By 1983, Waste Management was the largest waste disposal company in the United States.

The business model worked again with Blockbuster Video, which he started in 1985 and built into the leading movie rental chain nine years later. He opened a Blockbuster store every day, transforming a sleepy, five-store chain into the world’s largest video rental empire.

In 1996, he formed AutoNation and built it into a Fortune 500 company — becoming the only entrepreneur to have launched three Fortune 500 businesses.

“Some people dream of success, while other people get up every morning and make it happen,” he once said.

He sold Blockbuster at its peak for $8.4 billion to Viacom Inc. in 1994. Huizenga said he sold Blockbuster because of the threat of competing technologies but left Waste Management in 1984 only because he was tired of commuting from South Florida to its Chicago headquarters.

Huizenga was founding owner of baseball’s Florida Marlins and the NHL Florida Panthers — expansion teams that played their first games in 1993. He bought the NFL Miami Dolphins and their stadium in Miami Gardens for $168 million in 1994 from the children of founder Joe Robbie, but had sold all three teams by 2009.

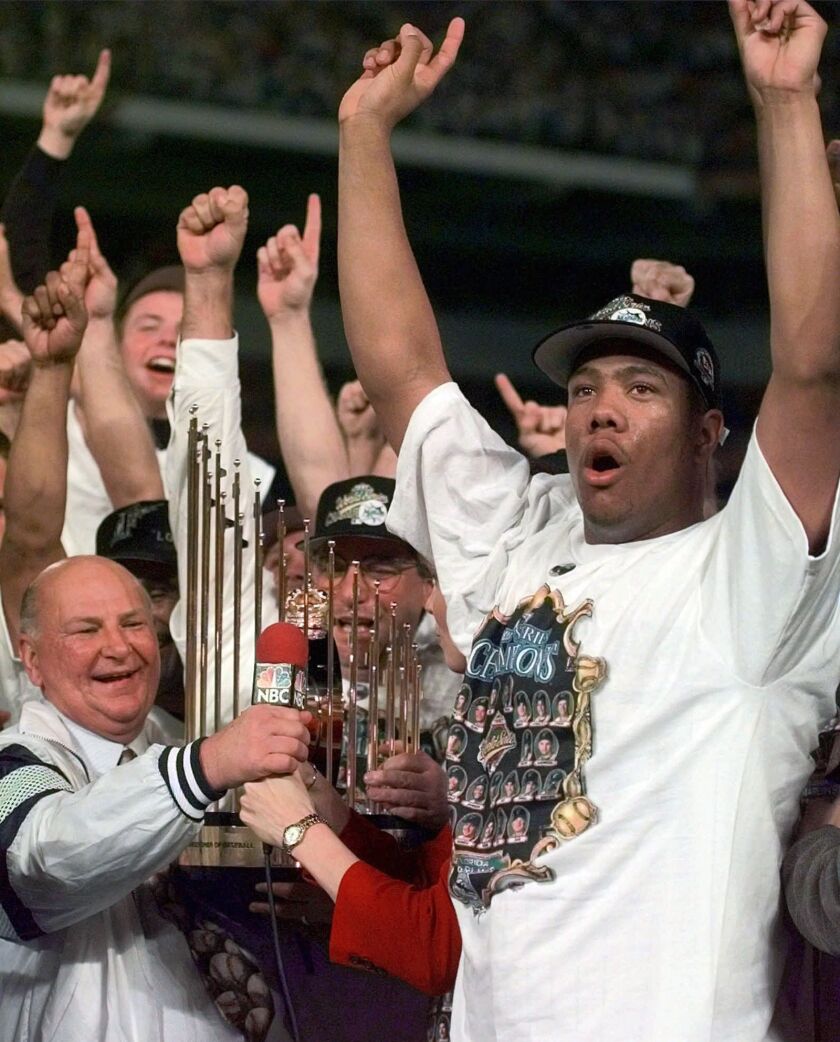

The Marlins won the 1997 World Series, and the Panthers reached the Stanley Cup Finals in 1996, but Huizenga’s beloved Dolphins never reached a Super Bowl while he owned the team.

“If I have one disappointment, the disappointment would be that we did not bring a championship home,” Huizenga said shortly after he sold the Dolphins to New York real estate billionaire Stephen Ross. “It’s something we failed to do.”

Huizenga earned an almost cult-like following among business investors who watched him build Blockbuster Entertainment into the leading video rental chain by snapping up competitors. He cracked Forbes’ list of the 100 richest Americans, becoming chairman of Republic Services, one of the nation’s top waste management companies, and AutoNation, the nation’s largest automotive retailer. In 2013, Forbes estimated his wealth at $2.5 billion.

For a time, Huizenga was also a favorite with South Florida sports fans, drawing cheers and autograph seekers in public. The crowd roared when he danced the hokey pokey on the field during an early Marlins game. He went on a spending spree to build a veteran team that won the World Series in the franchise’s fifth year.

But his popularity plummeted when he ordered the roster dismantled after that season. He was frustrated by poor attendance, losing money and his failure to swing a deal for a new ballpark built with taxpayer money.

Many South Florida fans never forgave him for breaking up the championship team. Huizenga drew boos when introduced at Dolphins quarterback Dan Marino’s retirement celebration in 2000, and he kept a lower public profile after that.

In 2009, Huizenga said he regretted ordering the Marlins’ payroll purge.

“We lost $34 million the year we won the World Series, and I just said, ‘You know what, I’m not going to do that,’” Huizenga said. “If I had it to do over again, I’d say, ‘OK, we’ll go one more year.’ ”

He sold the Marlins in 1999 to John Henry and sold the Panthers in 2001, unhappy with rising NHL player salaries and the stock price for the team’s public company.

Huizenga’s first sports love was the Dolphins — he had been a season-ticket holder since their first season in 1966. But he fared better in the NFL as a businessman than as a sports fan.

He turned a nifty profit by selling the Dolphins and the stadium for $1.1 billion — nearly seven times what he paid to become sole owner. But he knew the bottom line in the NFL is championships, and his Dolphins perennially came up short.

Huizenga earned a reputation as a hands-off owner and won raves from many loyal employees, even though he made six coaching changes. He eased Pro Football Hall of Famer Don Shula into retirement in early 1996, and Jimmy Johnson, Dave Wannstedt, interim coach Jim Bates, Nick Saban, Cam Cameron and Tony Sparano followed as coach.

In 2008, Huizenga’s final season as owner, the Dolphins had a turnaround year and won the AFC East on the final day of the regular season.

“It was a magical feeling,” Huizenga said. “I had tears in my eyes. I kept looking away so I wouldn’t have to wipe my eyes in front of everybody.”

Miami lost in the first round of the playoffs and didn’t return to the postseason until 2016. But Huizenga won praise from such disparate personalities as Shula, Johnson and Marlins manager Jim Leyland even when they no longer worked for him.

Harry Wayne Huizenga was born at Little Company of Mary Hospital in Evergreen Park on Dec. 29, 1937. His grandfather Harm had immigrated from the Netherlands in the early 1900s and built a suburban Chicago garbage hauling business, Huizenga & Sons Scavenger Co.

Huizenga attended Timothy Christian School until his father Gerrit, who made a fortune in construction, moved the family in the 1950s to Fort Lauderdale, where he finished high school. He attended Calvin College in Michigan before dropping out and serving for a time in the Army reserves.

He began his business career in Pompano Beach, Florida, north of Fort Lauderdale, in 1962, at 25, driving a garbage truck for $500 a month. He borrowed $5,000 from his father and bought a used truck to begin Southern Sanitation Service. As a young garbage collector, he’d wake up to drive trucks from 2 a.m. till noon, then shower before making a full day of sales calls.

In little more than a decade, his company, Waste Management Inc., became the world’s largest trash hauler.

One customer successfully sued Huizenga, saying that, during an argument over a delinquent account, Huizenga injured him by grabbing his testicles — an allegation Huizenga always denied.

“I never did that. The guy was a deputy cop. It was his word against mine, a young kid,” he told Fortune magazine in 1996.

He eventually bought out several competitors, expanding throughout South Florida. In 1968, he merged with the Chicago sanitation company his uncles owned, creating Waste Management Inc., which eventually became the world’s largest trash company.

That became his method of operation — becoming the first national player in industries that had been dominated by small and local operations.

He resigned from the company in 1984, taking $100 million in stock.

But retirement bored him, and he soon began buying dozens of small businesses like hotels and pest-control companies. In 1987, a business partner persuaded him to check out Blockbuster, a small chain of video stores. At the time, video stores were mostly locally owned mom-and-pop operations. Huizenga didn’t even own a VCR.

“I had an image of them being dark and dingy and dirty types of adult bookstores,” he told The Miami Herald. “But when I finally saw a Blockbuster store, it opened my mind.”

The stores were clean and carried 10,000 titles — 10 times more than the typical corner video store. He loved the concept and thought it could become the McDonalds of video. He and two partners bought 43 percent of the business for $19 million, and he became chairman and president. By 1991, the chain had grown to over 1,800 stores, with one opening every 17 hours, on average.

“The whole deal was to move quickly before our competition saw what we were doing and moved in on us,” he told the business magazine FSB in 2003.

In 1994, Viacom bought Blockbuster, then a publicly traded company, for about $8 billion.

In 1995, Huizenga got back into trash hauling by buying Republic Waste Industries Inc. for $27 million. Mergers and acquisitions soon followed. He renamed the company Republic Industries as it branched out, buying Alamo Rent-A-Car and National Car Rental.

Under Huizenga’s leadership, Republic started AutoNation, a national chain of car dealerships — again, an industry that had been dominated by local and regional ownership. At its peak, AutoNation had about 375 dealerships in 17 states.

Republic Services was spun off in 1998 to control the waste management portion of the portfolio, a sector that had grown to more than $1 billion in annual sales. He remained its chairman until 2002.

Huizenga was a five-time recipient of Financial World magazine’s “CEO of the Year” award and was the Ernst & Young “2005 World Entrepreneur of the Year.”

In 1960, he married Joyce VanderWagon. They got divorced in 1966.

He married his second wife, Marti Goldsby, in 1972. She died in 2017.

He is survived by four children — Wayne Jr., Ray, Scott and Pamela — and 11 grandchildren.

Huizenga became a large benefactor of Nova Southeastern University, a private school in Davie, Fla., where the Dolphins train. Its business school is named after him — even though he never completed college.

Regarding his business acumen, Huizenga once said: “You just have to be in the right place at the right time. It can only happen in America.”