MONTAUK, New York — Even after winter storms left East Coast harbors thick with ice, some of the country’s top chefs and trendy restaurants were offering sushi-grade tuna supposedly pulled in fresh off the coast of New York.

But that was just a fish tale. No tuna was landing there. The fish had long since migrated to warmer waters.

Consumers increasingly are paying top dollar for what they’re led to believe is local, sustainably caught seafood. But companies can hide behind supply chains that make it difficult to determine where fish comes from.

That’s where national distributor Sea To Table stepped in, guaranteeing its products were wild and directly traceable to a U.S. dock — sometimes to the boat that brought it in.

But an Associated Press investigation has linked the company to some of the same practices it vowed to fight. Preliminary DNA tests suggested some of its yellowfin tuna likely came from the other side of the world. Reporters traced the company’s supplies to migrant fishermen in foreign waters who described labor abuses, poaching and the slaughter of sharks, whales and dolphins. And the New York-based distributor offered species in Chicago and elsewhere that were illegal to catch, out of season and farmed.

Sea To Table has been a darling in the sustainable seafood movement, building an impressive clientele including universities and chefs such as Rick Bayless.

“It’s sad to me that this is what’s going on,” said Bayless, whose eight restaurants include Frontera Grill and Topolobampo.

Bayless said he loved the idea of being directly tied to fishermen — and the pictures and “wonderful stories” about their catch.

“This throws quite a wrench in all of that,” he said of the findings.

The AP staked out America’s largest fish market, followed trucks and interviewed fishermen on three continents. During one bone-chilling week, its photographers shot more than 36,000 time-lapse photos of a Montauk harbor — none showing any tuna boats docking while, at the same time, reporters worked with a chef to order fish supposedly coming from the seaside town. The boat listed on the receipt hadn’t been there in at least two years.

Reporters also tracked Sea To Table’s supply chain to fishermen abroad who make as little as $1.50 a day, working 22-hour shifts without proper food and water.

Sea To Table owner Sean Dimin said his suppliers are strictly barred from sending imports to customers and that violators would be dropped. “We take this extremely seriously,” Dimin said.

He said he communicated clearly to customers that some fish labeled as freshly landed at one port actually had been caught and trucked in from other states. Some chefs said that wasn’t the case.

The U.S. seafood market is worth an estimated $17 billion a year, with imports accounting for more than 90 percent of that. Experts say one in five fish is caught illegally worldwide, and a UCLA and Loyola Marymount study last year found nearly half of all sushi samples tested in Los Angeles didn’t match the fish advertised on the menu. A 2007 Chicago Sun-Times investigation used DNA testing on sushi bought at Chicago restaurants and found that cheaper types of fish routinely were sold as pricey red snapper.

Sea To Table offered a worry-free local solution, connecting chefs with more than 60 partners along U.S. coasts. The company predicts rapid growth — from $13 million in sales last year to $70 million by 2020, according to a confidential investor report obtained by the AP.

As business grew, Sea To Table has been saying one thing but selling another.

For caterers hosting a ball for Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, who had pushed through a law to combat seafood mislabeling, knowing where his fish came from was crucial. The Montauk tuna arrived with an email saying the fish was caught off North Carolina and a Sea To Table leaflet describing the seaside town.

But the boxes came from New York, with no indication the fish were landed in another state and driven more than 700 miles to Montauk. A week later, the caterer ordered the Montauk tuna again. This time, the invoice listed a boat whose owner later told reporters he didn’t catch anything for Sea To Table at that time.

“I’m kind of in shock right now,” caterer Brandon LaVielle said. “We felt like we were supporting smaller fishing villages.”

Some of Sea To Table’s partner docks, advertised as “just landed,” came from wholesalers and retailers that use imports.

Sea To Table also promoted fresh blue crab from Maryland in January, though the season closed in November.

And the company said it never sells farmed seafood, citing concerns about antibiotics and hormones. But red abalone advertised from central California actually are grown in tanks — it’s been illegal to harvest commercially from the ocean since 1997.

Dimin said farmed shellfish “is a very small part of our business, but it’s something that we’re open and clear about.”

Days later, he said he decided to drop aquaculture from his business because it contradicts his “wild-only” guarantee.

Private companies that mislead consumers, clients and potential investors could face lawsuits or criminal liability. Sellers who know, or should have known, fish is mislabeled could be found guilty of conspiracy to defraud the U.S. government, mail fraud and wire fraud.

Eric Hodge, a small-scale fisherman from Santa Barbara, said he considered partnering with Sea To Table a few years ago but quickly changed his mind after seeing canary rockfish on the distributor’s chef lists, though the fish was illegal to catch. He also learned that Sea To Table was buying halibut from the fish market, which relies heavily on imports. He said he told the company of his concerns.

“They are making money on every shipment, and they are not going to ask questions,” Hodge said.

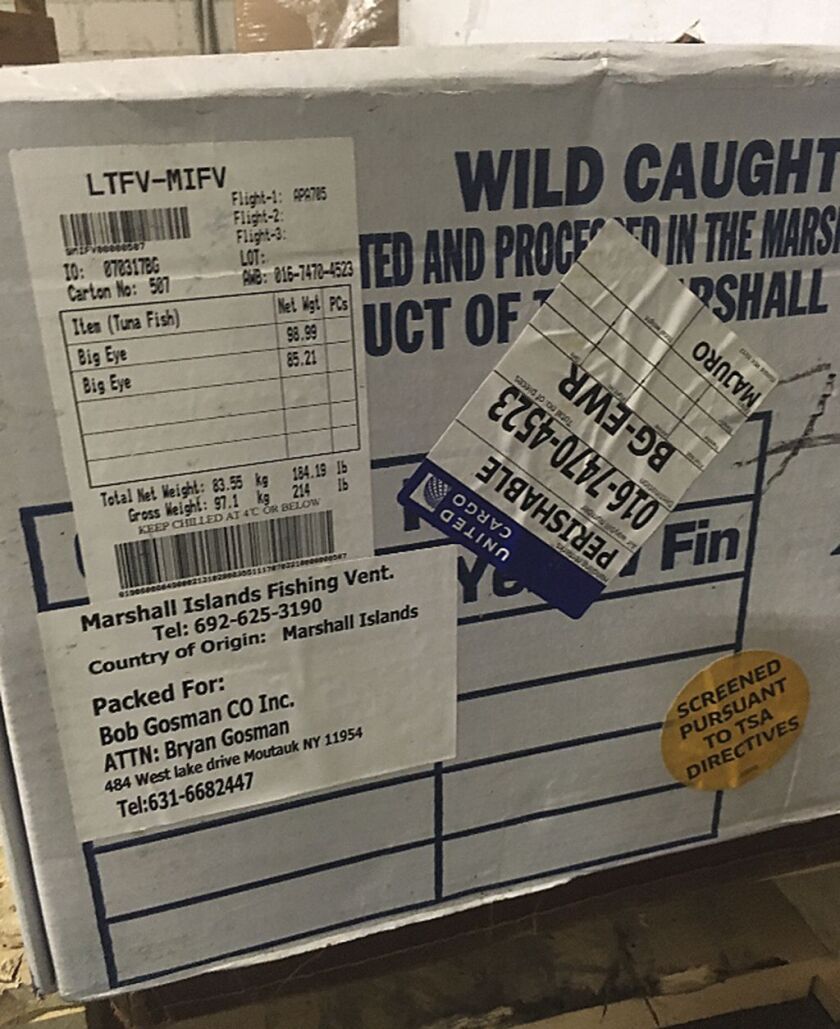

Boxes containing imported headless bigeye tuna sit on a pallet, marked to be picked up by a driver from the Bob Gosman Co., at the New Fulton Fish Market in New York. Bob Gosman Co., a supplier for Sea to Table, gets some of its fish from Fulton, a place in the state where many fish can always be found, regardless of the season. | AP

The idea for Sea To Table began with a family vacation to Trinidad and Tobago more than two decades ago. After a fishing trip there, Michael Dimin and his son Sean eventually started shipping fresh catch from the Caribbean nation to chefs in New York. Later, they shifted to working exclusively with small-scale, American coastal fishermen.

Restaurants and other buyers demanding sustainable products were drawn to the company. And they were willing to pay a lot — sometimes more than $20 a pound — for high-end species.

The New York Times, National Geographic, Bon Appetit magazine and others singled out Sea To Table as good guys in a notoriously bad industry. It worked with sustainability giants such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium, the Marine Stewardship Council and the James Beard Foundation.

Sea To Table’s products are sold in almost every state. It can be found at restaurants at O’Hare Airport, direct to consumers from its website and on Amazon for consumers to order.

Some of the biggest make-it-yourself meal kits have signed up. So have more than 50 colleges.

“Not OK,” Ken Toong, who is responsible for UMass Dining, told AP of Sea To Table. “We believed them.”

The investigation began with one of Sea To Table’s nearby suppliers. Located on New York’s eastern coast beyond the posh Hamptons, Bob Gosman Co. opened in Montauk as a mom-and-pop clam shack more than six decades ago.

Run by cousins Bryan and Asa Gosman, it’s a small empire sitting on a multimillion-dollar property. Gosman’s gets most of its tuna and other species from a place where fish can be found regardless of season: The New Fulton Fish Market outside Manhattan, which moves millions of pounds of seafood a night, much of it flown in from across the globe.

Beautiful maroon slabs of imported high-grade tuna were on display for several nights in December, January and February, as well as other times throughout last year. In the early hours, often between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m., boxes of fish bearing foreign shipping labels from all over the world were arranged into piles with “Gosman” scribbled across them in black marker. They were later hoisted onto a waiting truck with the same name.

After a three-hour drive east, the AP watched the loads arrive at the company’s loading dock in Montauk.

The tuna, swordfish and other species were ferried inside Gosman’s warehouse. They came from Blue Ocean in Brazil, Vietnam’s Hong Ngoc Seafood Co., and Land, Ice and Fish in Trinidad and Tobago. Occasionally, boxes were from Luen Thai Fishing Venture and Marshall Islands Fishing Venture. Luen Thai has a checkered past, including shark finning and a bribery scandal.

Though Sea To Table promised it would not take imports, with no yellowfin tuna landed in New York during the coldest months, Bryan Gosman said it was impossible to provide high-quality loins from Montauk. “So, in the beginning, there were times when we were trying to hustle around fish,” he said.

Eventually, with Dimin’s blessing, Gosman said he started getting fish from as far as North Carolina.

That arrangement stopped in March, according to Gosman, who said it wasn’t profitable. Dimin said they wanted to avoid the “complexity of communicating” their sourcing.

Meanwhile, in the dead of winter, AP turned to a chef to order $500 worth of fish. Sea To Table provided a receipt and assurances the seafood — which arrived overnight in a box bearing the company name and logo — was landed in Montauk a day before.

The invoice even listed the boat that caught it. But the vessel’s owner said it was hundreds of miles away.

The AP shipped tuna samples supposedly from Montauk to two labs for analysis: Preliminary DNA testing suggested the fish likely came from the Indian Ocean or the Western Central Pacific. There are limitations because using genetic markers to determine origins of species is an emerging science, but experts say the promising research eventually will help fight illegal activity.

Bryan Gosman said they keep Sea To Table’s fish separate but acknowledged there’s a chance imported tuna can slip through with domestic. “Can things get mixed up? It could get mixed up,” he said. “Is it an intentional thing? No, not at all.”

At the Fulton market, one of the boxes in Gosman’s stack was stamped with a little blue tuna logo above the words “Land, Ice and Fish,” out of Trinidad and Tobago.

That’s where the AP traced companies in Sea To Table’s supply chain to slave-like working conditions and destruction of marine life.

On learning that Sea To Table’s supply chain could be tracked to businesses engaged in labor and environmental abuses, Dimin called that “abhorrent and everything we stand against.” He said he was temporarily suspending operations with two partners to do an audit.

Sulistyo, left, an Indonesian fisherman who was forced to work on a foreign trawler that delivered fish to a Sea To Table supplier, watches local fisherman sort fish at a fishing port in Jakarta, Indonesia. Conscientious consumers, troubled by illegal practices plaguing the global seafood industry, were paying top dollar for what they believed was American-caught fish provided by national distributor Sea To Table. | AP

Contributing: AP journalists Julie Jacobson, Niniek Karmini