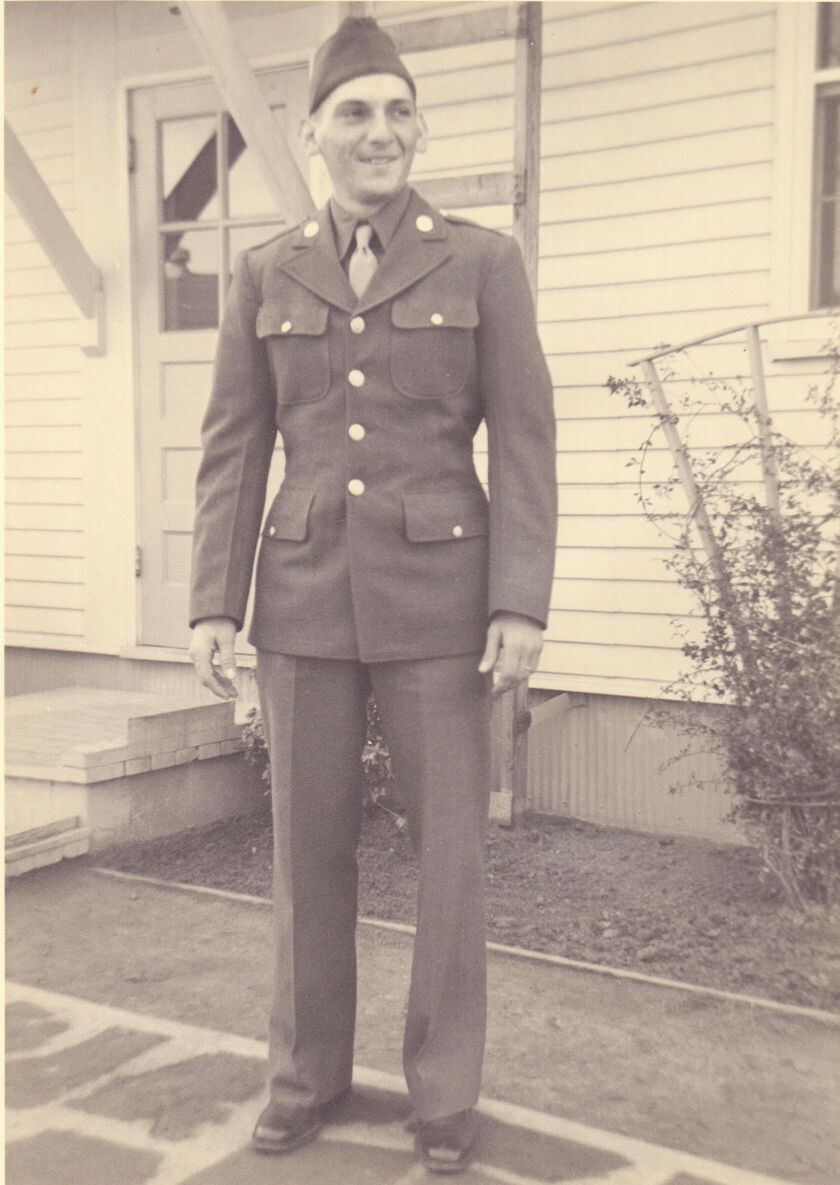

Having fought through North Africa, Sicily and Italy during World War II, Arnie Massier came home to Naperville, but he never forgot the moment a German soldier got the drop on him.

“All of a sudden, I got kicked in the leg,” he recalled 63 years after he became a GI. “And I turned around, and they had the zip pistol. . . . He had it right by my head. And he said, ‘For you, the war is over’ in English.

“I just dropped my rifle, and I just looked up at him,” he said. “Boy, I’m telling you, what a feeling that is. You don’t know when that trigger’s going to go off.”

While following orders from his German captors to move the wounded, his ammunition belt exploded, injuring his hands in 14 places. That caused pain and blood poisoning during the more than 18 months he was held as a prisoner of war.

At one point while being held captive, he was in such misery that he contemplated giving up.

But another soldier urged him to go on, saying, “ ‘Arnie, we’re going to walk,’ ” Mr. Massier said in an oral history. “They would have shot me.”

He kept on walking — until the day he escaped with other POWs by rolling down a hill, unnoticed.

And he kept walking when he returned to his hometown of Naperville, where he lived out his life in the house on Franklin Avenue where he was born in 1922 — and where he always flew the POW-MIA flag.

“He would walk around town five miles a day,” said his neighbor Jennifer Reichert. “He’d be down on the Riverwalk. If you were a little kid, he’d want to give you a dollar for ice cream. He grew beautiful roses. He’d tell people, ‘I’ll bring you a rose tomorrow.’ ”

Mr. Massier, 97, died Feb. 14 at Naperville’s Spring Meadows senior community, where he lived the last two months of his life.

Other than that, the war “was the only time he’d ever been away from home,” Reichert said. “He never stayed at a hotel. He didn’t go on vacation.”

“Everybody in the neighborhood loved him, took care of him,” said Pablo Araya, a Navy veteran and commander of Naperville’s VFW Post 3873. “At the funeral, it was all neighbors because he outlived everybody in his family.”

Mr. Massier never had any desire to leave Naperville. Maybe it was the sheer relief at making it back to the town he loved, where he’d set pins in a bowling alley as a boy. The place where his Austria-born parents raised chickens and brewed liquor during Prohibition. Where they’d danced around the house in celebration after, at his mother’s insistence, they’d gotten their money out of the bank just before the stock market crashed.

He worked for Kroehler Manufacturing in Naperville for more than 30 years.

“He was a furniture upholsterer,” Reichert said. “When he’d be napping, he’d be doing this thing with his hands. I asked him about it, and he said, ‘Oh, I’m making pleats.’ He was making pleats in his sleep.”

He and his brother Adam — also a WWII Army veteran — never married or had children. On warm days, they and their friends would hold court in downtown Naperville.

“They would sit on park benches at Main Street and Jefferson and watch Naperville go by,” said Bill Anderson, a past president of the Rotary Club of Naperville and owner of Oswald’s Pharmacy.

“He would sit there every day, and everybody knew who he was,” Araya said. “People loved to talk to him.”

Until the 1990s, Mr. Massier wouldn’t talk about the war. When he first returned to Naperville, he didn’t even want a homecoming parade, thinking about the time he and other POWs had been marched around Rome and pelted with rocks.

But then Reichert invited her neighbor to share his stories with her sixth-grade classmates at Washington Junior High School.

“He was supposed to be there for 10 minutes,” she said. “He spoke and spoke.”

The kids and teachers found his words so enthralling, she said, “They canceled the next class and then the next class.”

Mr. Massier became a popular speaker at Naperville schools, and he was honored in parades and at Wrigley Field.

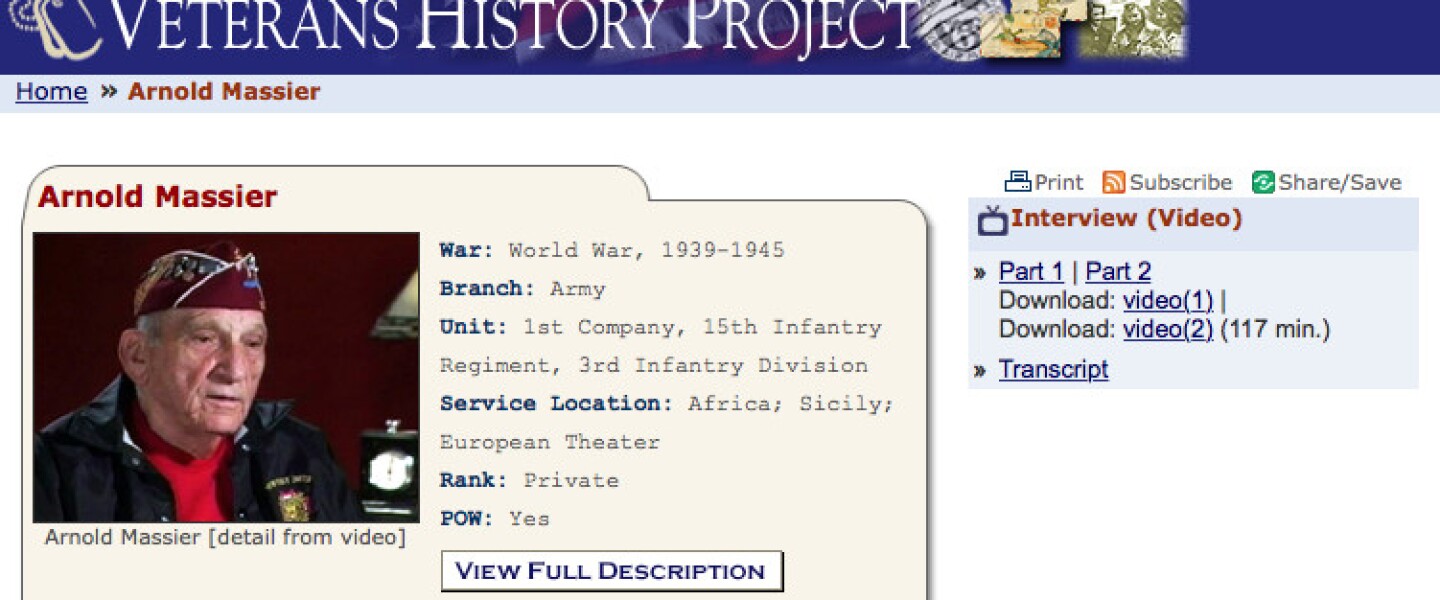

In 2007, he spoke with Elitsa Bizios, then a Columbia College Chicago student, for the oral history, which became part of the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project.

He told Bizios about being a prisoner at the sprawling Stalag 7-A near Munich and Stalag II-B and II-D in what’s now Poland. He battled malaria, hunger and lice and did forced farm labor.

Some camps also held civilians.

One day, “A little kid about 5 years old got shot right in front of me,” Mr. Massier recalled. “He was playing there. They have a wire, and that’s the warning wire....then, they have this barbed wire strung all over the place and then the guard sitting up on top. Two little kids were playing tag, and they told them to stop. He ain’t hurtin’ nobody. They warned them. They didn’t [stop]. Boom, killed them. About 5 years old, playing.”

In 2007, Arnold Massier was interviewed for an oral history that became part of the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project.

Library of Congress

“He lamented that his entire life,” Reichert said. “It was so wrong, and there was nothing he could do.”

Because his parents were from Austria, Mr. Massier understood German. He spoke of a German soldier’s cries after being shot.

“He hollered ‘Dear Lord’ first. Then. he hollered for his mother and dad and brother and sister. . . .He says, ‘Why did you shoot me?’ I thought, hey, you’re coming toward me. You woulda got me first.”

He remembered the day he and his fellow GIs killed 298 men in a single battle. How they moved through Italy with such force that they were dubbed “Truscott’s Trotters” after their general, Lucian Truscott.

As the Allies surged, he said prisoners were forced to walk toward the interior of Germany during an 800-mile march that lasted from January to mid-April 1945.

“There were some Russians with us, guys that were about 70 years old, they were crying they couldn’t walk no more,” he told Bizios. “The Germans walked up to ’em and shoot ’em in the head and throw a blanket over ’em and just kept right on walking.”

After covering 110 miles in three days, “We got a potato that big,” Mr. Massier said, holding up his hand to make a tiny circle.

When he and other GIs rolled down the hill to escape, they found refuge in a nearby town. But a moment of high alert came when a German with a rifle showed up, Mr. Massier said. “He said, what are you doing here?” he told Bizios. “ ‘We’re prisoners.’ ”

To their relief, “He says, ‘Hang Hitler from the highest pole.’ He was a deserter.”

When they located American tanks, “Oh, geez, you cried. You’re free. You never forget it,” he said in another interview with Bizios, who became a friend, for Naperville Community Television Channel 17.

But some details he kept to himself. After escaping, he was on a transport plane.

“A guy come from Glen Ellyn, the pilot. He says, ‘My brother’s a prisoner,’ he said. ‘D’you know him?’ I says, ‘There’s so many prisoners, you don’t know who’s who.’

“I couldn’t tell the guy what they did to the American pilots. . . They pitchforked a lot of them.”

Later, in a military hospital, “The radio was playing music, and all of a sudden it said, ‘Flash — Indianapolis sunk,’ ” he said.

His brother George was on the ship and died in the torpedo attack.

Later, it became known that sailors who survived the infamous attack floated for days in the water, some getting attacked by sharks.

“He always struggled with it,” Reichert said, but comforted himself with the thought his brother must have died quickly, saying, “I don’t think George could swim too well.”

He remembered lighter moments, too. Like the time he visited a British ship in Casablanca and saw the cook using his feet to turn lamb meat into sausages.

“There was a big wooden tub, and you could see the grease hanging, the outside of it. He was in there, barefooted, stomping sausage in there,” he told Bizios. “From then on I went in the PX and got a little can of salmon, chocolate bars. That’s what I ate.”

Or the time soldiers realized a makeshift latrine in Sicily contained a deadly surprise.

“They holler for the sergeant to bring down a flashlight,” he said, according to a transcript of his oral history. “There was a bomb in there . . . . They could have all went sky high.”

With his death, “We really lost a page of history,” said Army veteran Ken Garhan, 86, a former VFW Post 3873 commander.

“I’m not a brave guy,” Mr. Massier once said of his service. “I’m just another GI ‘dogface.’ That’s all I am. I’m doing what I’m supposed to do.”