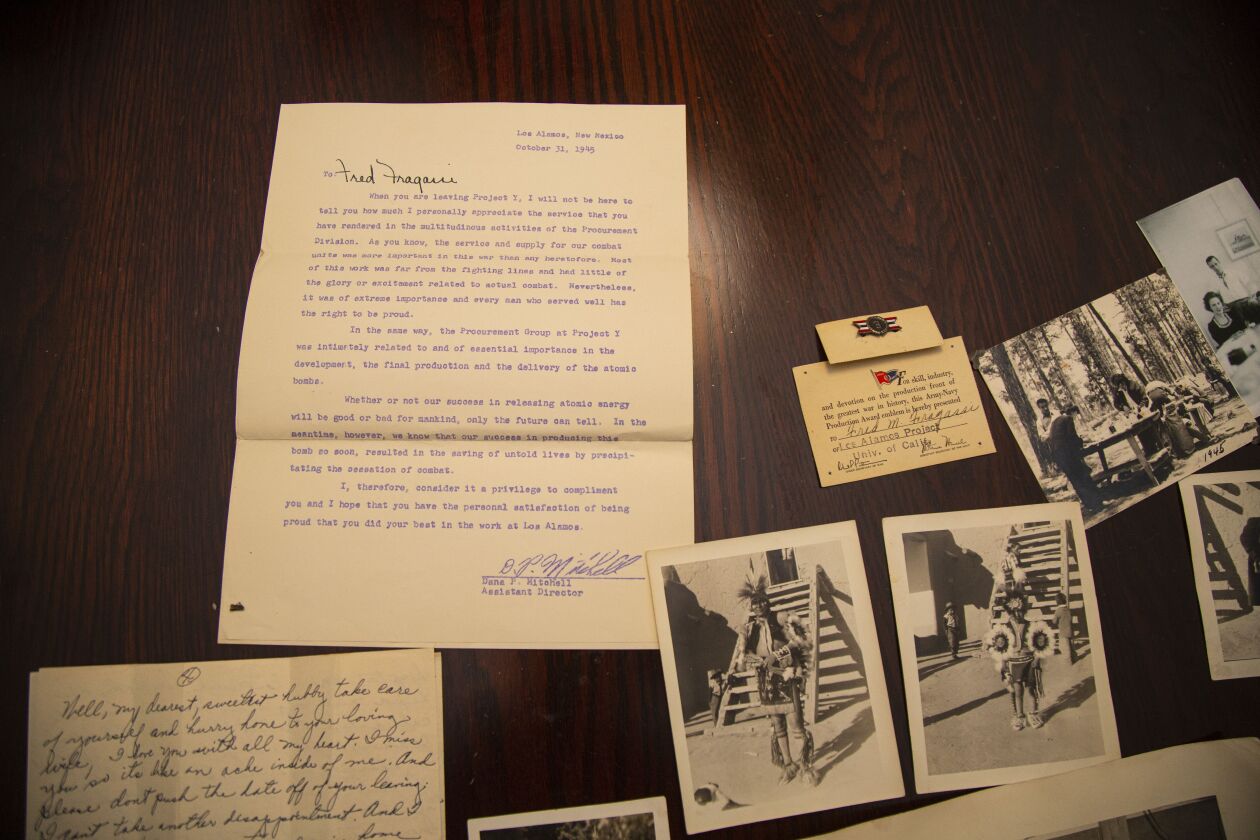

In a letter Oct. 31, 1945, Dana P. Mitchell, head of equipment procurement for the Manhattan Project — the top-secret government project that created the atomic bombs that ended World War II — bade farewell to workers under his supervision.

“Most of this work was far from the fighting lines and had little of the glory or excitement related to actual combat. Nevertheless, it was of extreme importance,” Mitchell wrote to them. “Whether or not our success in releasing atomic energy will be good or bad for mankind, only the future can tell.”

Seventy-five years later, as we mark the anniversaries this month of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Mitchell’s words remain chilling — especially gripping his letters in my hands.

They were addressed to my grandparents, Fred and Clara Fragassi.

It was only by happenstance that this modest Italian American couple from Evanston ended up living in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and working on “history’s biggest secret” for two years, between 1944 and 1946.

Before they uprooted their lives, Fred and Clara’d been working at the Wieboldt’s department store at Church Street and Oak Street. They had first met there years before — she working in the gifts department, he as a chauffeur and delivery driver — before marrying at the former St. Callistus Church in Chicago’s Little Italy in 1937.

By the time World War II broke out a few years later, my grandfather had been given a 4-F distinction for a minor health condition that precluded him from being allowed to enlist for combat, and jobs were drying up in Chicago.

His sister Josephine and her husband Marty were living in New Mexico, where Marty was stationed with the Army. They wrote home to my grandfather about work in the remote town of Los Alamos.

And so Fred and Clara loaded up their DeSoto with their belongings and their son Phil, who was 6 years old, and made their way to begin work on what was known to them only as Project Y.

“The Manhattan Project was undertaken with great urgency and great secrecy because there was concern of espionage,” says Dan Meyer, director of special collections at the University of Chicago Library, who curated an exhibit that can now be viewed online about Chicago’s ties to the Manhattan Project. “The U.S. was aware that German scientists were also working on projects related to nuclear energy, and there was fear they would develop a bomb before the Allies.”

At the U. of C., a team led by Italian physicist Enrico Fermi produced the world’s first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in 1942 before Los Alamos — a remote site beloved by Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer — was established in 1943. The Hyde Park campus’ metallurgical laboratory also sent recruits to New Mexico.

Though they weren’t scientists, my grandfather found a role working in the supply warehouse, and my grandmother apparently was hired for a job in the cafeteria.

Every job at the time was seen as essential, with a huge effort needed to support the scientists, according to Alan B. Carr, senior historian of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

“People will think about Nobel laureates and all these famous scientists who were obviously very important, but the Manhattan Project simply would not have happened without all these other people, like construction workers and secretaries, people that ran warehouses and made sure that shipments were received,” Carr says.

Though many sites played a part in this national undertaking, which employed half a million people at one point or another (other notable locations included Hanford, Washington, and Oak Ridge, Tennessee), Los Alamos was one of the best-known because it was the site of the actual fabrication.

Carr estimates that 8,000 people — a workforce that was 11 percent women — worked at Los Alamos at its peak in 1945-46. Even after the war ended, work continued until the federal Atomic Energy Commission took over the site on Jan. 1, 1947.

Fred and Clara are long gone. He died in 1992, she in 1983.

But they left us an incredible array of rare mementos, photos and papers. Those items — along with my late Uncle Phil’s accounts before his death in 2011 and my father’s secondhand stories — have allowed my brother Joe and I to piece together the story of a generation far removed from us, people we never really got to know.

“It’s amazing we have as many of these pieces as we do,” says Joe. “It was very out of the ordinary for this little Evanston couple to have all these amazing photos and documents you can’t find in history books.”

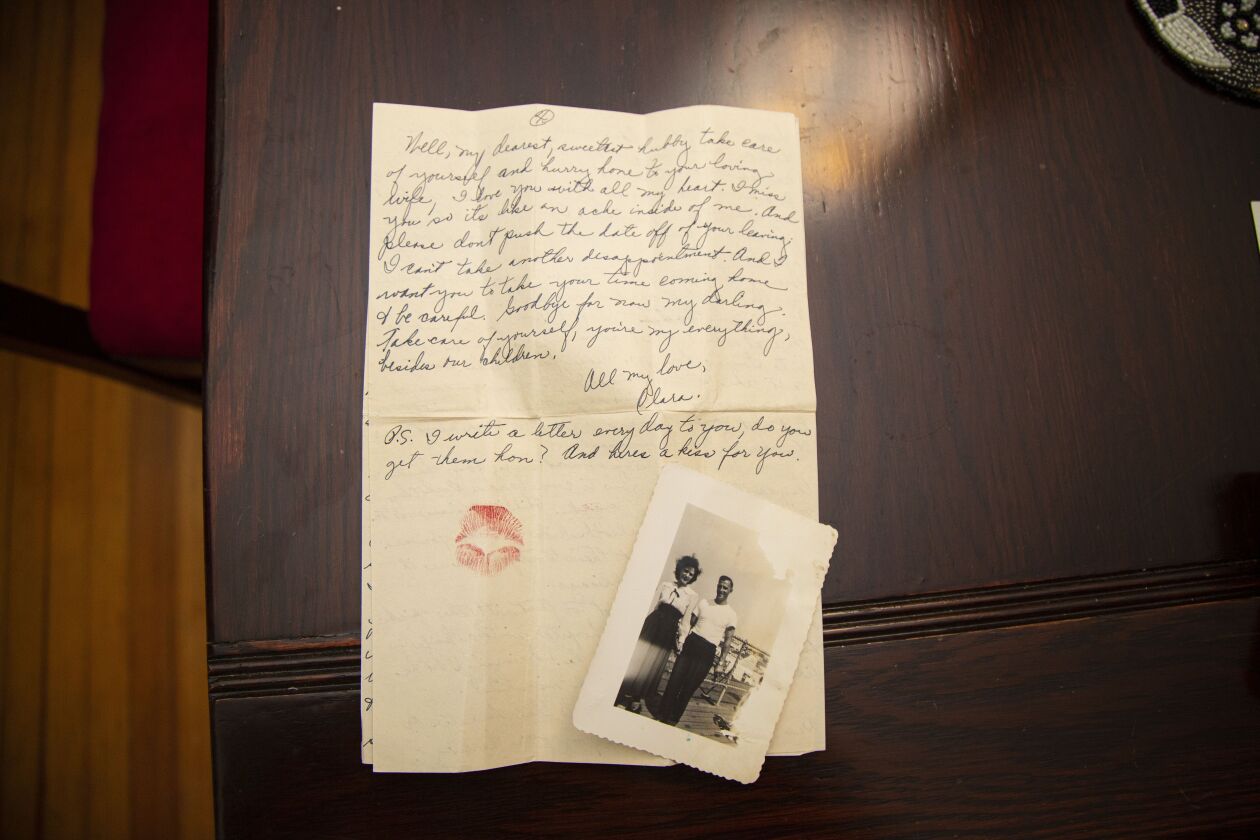

In addition to the letters from Mitchell and a work “certificate of completion” from Secretary of War Henry Stimson, the trove also includes time-traveled black-and-white photos and a precious series of letters that my grandmother wrote to my grandfather after returning to the Chicago area.

Clara had just had her second baby, our Uncle Joe, and was missing home. But she was anxious about flying, so Fred packed up the DeSoto once more and drove her and the kids back home to Evanston in 1946 to be with extended family before making the return 1,275-mile journey to Los Alamos.

That’s when their letters to each other began.

“I heard the broadcast today about the Los Alamos blast where one fellow was killed and two injured. They’re sure getting careless!,” my grandmother said in a letter to my grandfather dated Aug. 5, 1946.

That turned out to have been the result of a homemade smoke bomb, according to Carr, based on the records he was able to access. The fatality was among 22 at Los Alamos between 1943 and 1945.

In other letters, my grandmother pleads for my grandfather to not “push off the date of your leaving.”

She sealed each letter with a kiss, her bright red lipstick still vibrant on the page 75 years later.

My grandfather didn’t want to leave the beauty of New Mexico. He was offered 800 acres for just $1 an acre and “always regretted not buying it,” my brother Joe says.

Though their work at Los Alamos was hard, Fred and Clara had time to take in some culture, too. Many of the pictures show them exploring Bandelier National Monument and socializing with the native Pueblo people, many of them also hired to work service jobs on the Manhattan Project. My grandfather developed a friendship with an elder, who welcomed the Fragassis for ritual ceremonies at the nearby San Ildefonso reservation and gave them several heirloom jewelry pieces.

There also are pictures from my grandparents’ vacation to nearby Juarez, Mexico, and others showing Fred’s bandaged thumbs from playing in a baseball league in Los Alamos.

My grandfather returned home to Evanston in the fall of 1946. He owned a Standard Oil gas station and later worked for the Evanston Police Department in safety testing.

My grandmother found full-time work at Evanston City Hall in data processing, where she worked until she retired.

But their time in a pivotal moment in history was never far from their memories, even as others’ perceptions of the events that led to the end of the war evolved.

“Inevitably, our viewpoint now is a mixed one,” Meyer says. “There’s the effects of the weapon that was developed and its consequences we still live with. But it was also this incredibly remarkable achievement and an accomplishment that took place in a relatively short period of time. And ever since large-scale projects like this are referred to Manhattan Project-type efforts. It forever changed history.”

Selena Fragassi is a freelance writer.