The U.S. Army has hidden or downplayed the extent to which its firearms disappear, significantly understating losses and thefts even as some weapons are used in street crimes.

The Army’s pattern of secrecy and suppression dates back nearly a decade, when The Associated Press began investigating weapons accountability within the military. Officials fought the release of information for years, then offered misleading answers that contradict internal records.

Military guns aren’t just disappearing. Stolen guns have been used in shootings, brandished to rob and threaten people and recovered in the hands of felons. Thieves sold assault rifles to a street gang.

Army officials cited information that suggests that only a couple of hundred firearms vanished during the 2010s.

But internal Army memos show losses many times higher.

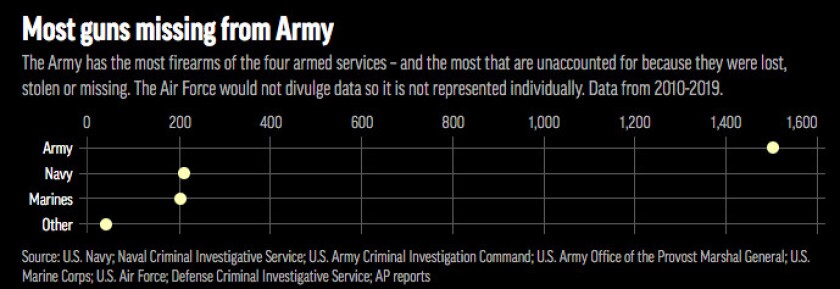

Altogether, an AP investigation of AWOL weapons from all branches of the military found that at least 1,900 military firearms were stolen or lost during the 2010s, some of them resurfacing in violent crimes.

Government records covering the Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Air Force show pistols, machine guns, shotguns and automatic assault rifles have vanished from armories, supply warehouses, Navy warships, firing ranges and other places where they were used, stored or transported.

These weapons of war disappeared because of unlocked doors, sleeping troops, a surveillance system that didn’t record, break-ins and other security lapses that, until now, have not been publicly reported.

Military explosives also were lost or stolen — including armor-piercing grenades that ended up in an Atlanta backyard.

Weapon theft or loss spanned the military’s global footprint, touching installations from coast to coast, as well as overseas. In Afghanistan, someone cut the padlock on an Army container and stole 65 Beretta M9s. The theft went undetected for at least two weeks, until empty pistol boxes were discovered in the compound. The weapons were not recovered.

Even elite units aren’t immune. A former member of a Marines special operations unit was busted with two stolen guns. A Navy SEAL lost his pistol during a fight in a restaurant in Lebanon.

In the wake of the AP investigation, Army Secretary Christine Wormuth told a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee that she would be open to new oversight on weapons accountability. The Pentagon used to share annual updates about stolen weapons with Congress, but the requirement to do so ended years ago, and public accountability has slipped.

“There must be full accountability in Congress with regular reporting of missing or stolen weapons,” U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said.

The Army and Air Force couldn’t readily say how many weapons were lost or stolen from 2010 through 2019. So the AP built its own database, using extensive federal Freedom of Information Act requests to review hundreds of military criminal case files and property loss reports as well as internal military analysis and data from registries of small arms.

Sometimes, weapons disappear without any paper trail. Military investigators regularly close cases without finding the firearms or person responsible because shoddy records lead to dead ends.

The military’s weapons are especially vulnerable to corrupt insiders responsible for securing them. They know how to exploit weak points within armories or the military’s enormous supply chains. Often from lower ranks, they might see a chance to make a buck from a military that can afford it.

“It’s about the money, right?” said Brig. Gen. Duane Miller, who as deputy provost marshal general is the Army’s No. 2 law enforcement official.

Theft or loss happens more than the Army has publicly acknowledged. During an initial interview, Miller significantly understated the extent to which weapons disappear, citing records that report only a few hundred missing rifles and handguns. But an internal analysis AP obtained, done by the Army’s Office of the Provost Marshal General, tallied 1,303 firearms.

In a second interview, Miller said he wasn’t aware of the memos, which had been distributed throughout the Army, until AP pointed them out following the first interview. “If I had the information in front of me,” Miller said, “I would share it with you.” Other Army officials said the internal analysis might overstate some losses.

The AP’s investigation began a decade ago. From the start, the Army has given conflicting information on a subject with the potential to embarrass — and that’s when it has provided information at all. A former insider described how Army officials resisted releasing details of missing guns when AP first inquired, and indeed that information was never provided.

Top officials within the Army, Marines and Secretary of Defense’s office said that weapon accountability is a high priority and that, when the military knows a weapon is missing, it triggers a concerted response to recover it. The officials also said missing weapons are not a widespread problem and noted that the number is a tiny fraction of the military’s stockpile.

“We have a very large inventory of several million of these weapons,” Pentagon spokesman John Kirby said. “We take this very seriously, and we think we do a very good job. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t losses. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t mistakes made.”

Kirby said those mistakes are few, though, and last year the military could account for 99.999% of its firearms.

“Though the numbers are small, one is too many,” he said.

In the absence of a regular reporting requirement, the Pentagon is responsible for informing Congress of any “significant” incidents of missing weapons. That hasn’t happened since at least 2017.

While a missing portable missile such as a Stinger would qualify for notifying lawmakers, a stolen machine gun would not, according to a senior Department of Defense official whom the Pentagon provided for an interview on condition the official not be named.

The AP’s analysis covered the 2010s, but instances of military firearms being stolen persist. For example, in May, an Army trainee who fled Fort Jackson in South Carolina with an M4 rifle hijacked a school bus full of children, pointing his unloaded assault weapon at the driver before eventually letting everyone go.

Stolen military guns have been sold to street gang members, recovered on felons and used in violent crimes. The AP identified eight instances in which five different stolen military firearms were used in a civilian shooting or other violent crime, and others in which felons were caught possessing weapons.

To find these cases, reporters combed investigative and court records as well as published reports. Federal restrictions on sharing firearms information publicly mean the case total is certainly an undercount.

The military requires itself to inform civilian law enforcement when a gun is lost or stolen, and the services help in subsequent investigations. The Pentagon does not track crime guns, and Kirby said his office was unaware of any stolen firearms used in civilian crimes.

The closest thing to an independent tally was done by the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services. It said 22 guns issued by the U.S. military were used in a felony during the 2010s. That total could include surplus weapons the military sells to the public or loans to civilian law enforcement.

Those FBI records also appear to be an undercount. They say that no military-issue gun was used in a felony in 2018, but at least one was.

Efforts to suppress information about AWOL military firearms date to 2012, when AP filed a Freedom of Information Act request seeking records from a registry where all four armed services are supposed to report firearms loss or theft.

The former Army insider who oversaw this registry described how he put together an accounting of the Army’s lost or stolen weapons but later learned that his superiors blocked its release.

As AP continued to press for information, including through legal challenges, the Army produced a list of missing weapons that was so clearly incomplete that officials later disavowed it. They then produced a second set of records that also did not give a full count.

Secrecy surrounding a sensitive topic extends beyond the Army. The Air Force wouldn’t provide data on missing weapons, saying answers would have to await a federal records request AP filed a year and a half ago.

The broader Department of Defense also has not released reports of weapons losses that it receives from the armed services. It would only provide approximate totals for two years of AP’s 2010 through 2019 study period.

The Pentagon stopped regularly sharing information about missing weapons with Congress years ago, apparently in the 1990s.

Contributing: Lolita Baldor, Dan Huff, Brian Barrett, Justin Myers