Before the pandemic hit, Jacqueline Bartley, a mother of two girls and a boy, had a comfortable life.

Then, the 41-year-old lost her job with American Airlines, quickly went through her savings and found herself months behind on the $1,350-a-month home she rented after having never befre missed a rent payment.

Bartley, who lives in Durham, North Carolina, turned to the state’s rental assistance program and was relieved in January to be awarded $8,100. But she says her landlord refused the money after she rejected his request to cut the length of her two-year lease. The program required landlords to honor leases, among other conditions, to get the money.

She turned to a second program, recently launched by the state, and again was approved. Now, she recently learned that her landlord had accepted nearly $20,000 for back rent and three months of future payments and agreed to dismiss his eviction lawsuit.

That means she won’t be forced from her home after the federal eviction moratorium ends July 31. But the uncertainty meant months of anxiety.

“It’s been crazy, especially when you have children in school,” Bartley said. “OK, am I going to have somewhere to go each month?”

Millions have found themselves in situations similar to Bartley’s, facing possible eviction despite promises by governors to help renters after Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020.

Nationwide, state leaders set aside at least $2.6 billion from the CARES Act’s Coronavirus Relief Fund to prop up struggling renters. But now, a year later, more than $425 million of that — 16% — hadn’t made it into the pockets of tenants or their landlords, an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity and The Associated Press has found.

“It’s mind-boggling,” said Anne Kat Alexander, a project manager with Princeton University’s Eviction Lab. “I knew there were problems, but that’s a huge amount of money not to be disbursed in a timely manner.”

Like many state leaders, North Carolina’s Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper pledged to roll out an ambitious program last year offering tens of millions of dollars in federal aid to help cover unpaid rent.

But it took months to start, and it stopped accepting applications just weeks after it finally opened in October due to overwhelming demand. The 20 nonprofits designated to distribute the money often lacked the capacity to quickly do so.

Then, faced with the Republican-controlled legislature’s takeover of CARES Act spending in January, the state had less money to award applicants. It ultimately spent $133 million of a promised $167 million.

“There was a lot of poor execution in rolling out that first program,” said Pamela Atwood, director of housing policy for the North Carolina Housing Coalition.

The federal government has sent tens of billions of dollars more in rental assistance to states in 2021, but that’s been slow to get disbursed, too.

<!— start AP embed —><iframe title=”$1 out of every $6 in 2020 rental assistance spent elsewhere” aria-label=”table” id=”datawrapper-chart-cliGc” src=”https://interactives.ap.org/embeds/cliGc/1/” scrolling=”no” width=”100%” style=”border:none” height=”559”></iframe><script type=”text/javascript”>!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var e in a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-”+e)||document.querySelector(“iframe[src*=’”+e+”’]”);t&&(t.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][e]+”px”)}}))}();</script>

<!— end AP embed —>

MONEY SHIFTED AWAY FROM RENT AID

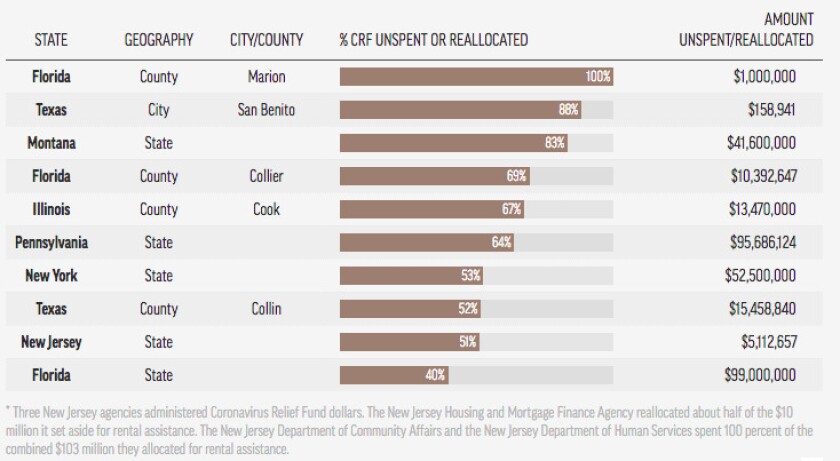

Seventy state and local agencies set aside $2.7 billion from the federal Coronavirus Relief Fund in 2020 for rental assistance programs. More than $425 million of that either ended up being reallocated for other COVID-related expenditures or remained unspent by March 31, 2021.

Center for Public Integrity, AP

With the first round of money in 2020, bureaucracy wasn’t the only problem. Politics also played a role, with a handful of states, many led by Republicans and with a history of weak tenant protections, offering little or no assistance.

Then, there was the often onerous application process. An end-of-the-year federal deadline for spending the money was extended so late that some states already had pulled funding to use on other expenses. Some landlords refused to participate over restrictions that meant they couldn’t evict a tenant who fell behind again. Tenants sometimes shortchanged themselves by filing incomplete applications.

Congress’ 2020 CARES Act sent billions of dollars to states and some local governments. But it didn’t mandate that any money be spent on rental assistance, leaving it to states to set the rules.

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s database of rent-relief programs in 2020, Georgia, West Virginia and Tennessee, all with Republican governors, chose not to set up statewide rent-relief programs last year despite having higher-than-average eviction rates historically. South Carolina allocated less than $14 per renter-occupied household.

Georgia’s Department of Community Affairs tried to set up a rental assistance program with money from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. But, when it became clear that a larger amount of money would be coming from the U.S. Department of Treasury in 2021, the program stalled, said Susan Reif, housing unit director for Georgia Legal Services Program and director of the Eviction Prevention Project.

Still, many states scrambled to act, creating massive programs to keep families in their homes. By last summer, state and local government officials had launched about 530 rental assistance programs, setting aside at least $4.3 billion from various sources.

Several states won praise for well-run programs. Illinois, Indiana, Oregon and Washington state were among more than a dozen that reported distributing every dollar of the rental assistance set aside from the Coronavirus Relief Fund by March 31.

The Center for Public Integrity surveyed about 70 state and local agencies that the National Low Income Housing Coalition identified as having set aside Coronavirus Relief Fund money for rent help in 2020. About $1 of every $6 of that $2.6 billion ended up being spent on other COVID-19-related expenses, such as protective equipment, police officers’ salaries and small-business loans.

Some states also spent millions setting up their programs, including North Carolina, which allocated around $20 million on administrative costs.

Diane Yentel, executive director of the National Low Income Housing Coalition, said the funding challenges led Congress to set aside nearly $47 billion for emergency rental assistance in December and March.

“Some states and cities carved out some of those funds for eviction prevention and to create emergency rental assistance programs,” Yentel said. “But many didn’t, or many didn’t set aside enough.”

The Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency got $150 million to help renters. but about $96 million tof that ended going to plug holes in the state’s public safety budget. The Florida Housing Finance Corporation set aside $250 million for rental assistance but returned about $99 million to the state treasury to be spent on other programs. New York ended up spending only $47.5 million of the $100 million promised for rental assistance.

POLITICS’ ROLE IN RENT AID

“It’s just horrifying how ill-prepared some states were,” Alexander said. “Some places made it work, and some places didn’t.”

Dylyn Price said she got about $5,800 in rental assistance but that the money might not be enough to keep her from losing her home in Athens, Ga. After her pay and hours at a fast-food restaurant were cut, eviction notices started arriving in early 2020.

Price got rental assistance from the Ark, a nonprofit administering CARES Act funding for the city of Athens. But the aid ended earlier this year. And Price’s landlord has refused to renew her expiring lease.

She fears that she and her 14-year-old son will again have to stay in a homeless shelter.

“It’s a very nauseating and uncomfortable situation to be in,” Price said.