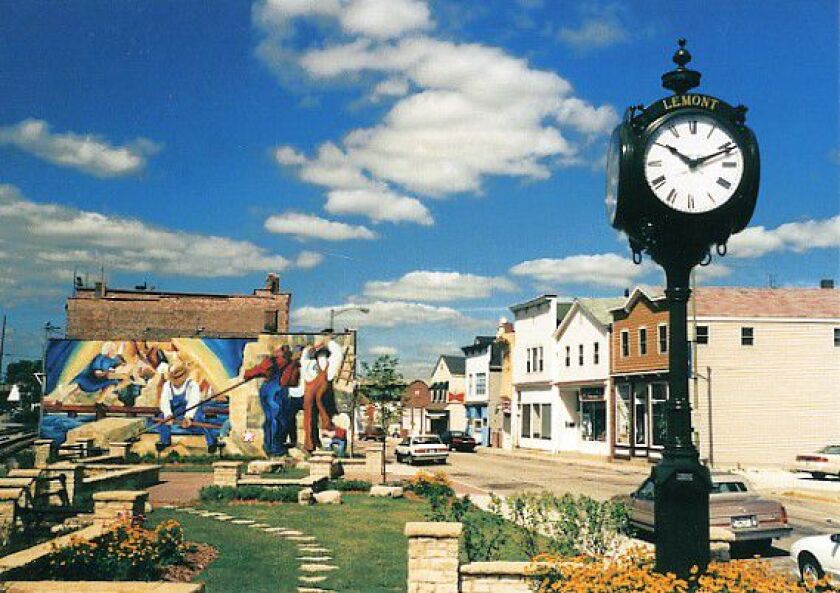

The mural — also known as “The Stonecutters” — honors the labor of limestone workers in the 19th century, many of them immigrants. It became an instant artistic centerpiece in the suburb about 30 miles southwest of Chicago.

“There’s so much history in this town, and it begins right here,” Lemont community relations manager Linda Molitor, standing downtown in Budnik Plaza, says of the scaffold-covered mural on the side of a restaurant. “That’s because it depicts the history of quarry and canal workers who built this town and who contributed to the economic success of Chicago.”

The buff-colored Lemont dolomite limestone laid the foundation for Lemont — physically and economically. And it was used to build such Chicago architectural icons as the Water Tower and Pumping Station and Holy Name Cathedral.

In 1993, the mural having weathered, village officials again turned to Yasko. Then living in Wisconsin, she came back to restore the wall.

She did it again in 2000. Then 59, Yasko used a pneumatic chisel to blast all of the paint off the 1,000-square-foot, concrete-block wall and recreated in acrylic paint what she’d done a quarter century earlier in enamel.

Each time, Yasko says, she stuck around for a couple of months and became involved in the life of the community.

Recently, Yasko returned for a third refresh. She and her assistants moved into an inn and started work on the wall in early September. By the time they left in early October, its once-vibrant reds, blues and yellows popped out again.

And, even at 80, she climbed the scaffolding like someone a fraction her age.

“I’m relishing this one partly because of my age,” says Yasko, wearing paint-splattered white overalls, as she took a break on a gorgeous fall afternoon. “I’ve just decided I’m going to totally enjoy this project. But I did train for it. It’s a physical job. I would not do any heroics.”

Yasko was one of the first women doing outdoor public murals in and around Chicago. Her first, in 1972, was “Under City Stone,” painted in the 55th Street underpass in Hyde Park. She finished restoring that mural in 2015 after a years-long effort.

So working on the Lemont mural once more was like a homecoming.

“They know how to make public art an asset in their community,” the artist says. “They appreciate its value, and that’s an important thing. Just the idea that the city wants us to be here, to keep their asset shining — that’s really wonderful.”

“It’s a significant piece of art for our village, and we don’t want to have it go away,” says Molitor, who contacted Yasko about refurbishing the wall. “I don’t think there was ever a question that upkeep was not going to be done.”

Molitor expects the mural, which cost about $35,000 to restore, to last longer thanks to the new types of paint and varnish used.

Rob Moriarty, a founding member of Lemont’s Art and Culture Commission, worked with Yasko on the restoration. He remembers seeing the mural when he was growing up in Lemont. He later moved to Chicago, where he helped create numerous community murals and mosaics. Since moving back to his hometown in 2004, he’s done many public art works with Mona Parry, including a mural commemorating Lemont’s 1885 quarry workers’ strike and massacre, in which the Illinois militia killed three men.

Moriarty, who’s an art teacher at Morton West High School in Berwyn, says he knew of Yasko’s national stature as a muralist.

“She’s somebody with a long history and who’s been a part of history,” he says. “Understanding her role and appreciating the work she did and then getting to work with her, it was a pretty amazing experience as an artist.”

The mural’s origins date to 1975, when the Lemont Bicentennial Commission and the Lemont Area Historical Society invited Yasko, then the workshop coordinator for the Chicago Mural Group, to consider creating a mural to mark the nation’s 200th anniversary. She visited several times, interviewed Lemont residents, did some historical research and held meetings to get ideas and feedback.

“I try to make connections with residents and to find out what’s the underlying source of pride for these people,” Yasko says.

The budget back then was about $4,000, paid for through donations from the civic groups that were matched by National Endowment for the Arts.

From her first sketch, Yasko envisioned workers levering and breaking blocks of stone in an open pit and also showing the area’s waterways and spires of stone-built churches. A former quarry worker posed for Yasko as a model for the man in the mural with a sledgehammer.

There are no more working quarries around Lemont. The old pits have been converted into lakes.

There’s one image in the mural that didn’t ring true with Lemonters — that of the woman in the upper left corner lifting a slab. Women didn’t work in the quarries, they said. Yasko told them that was meant to be symbolic of women’s “participation and support” in building the community. The female figure stayed.

Yasko moved for a time to Lemont, staying with town historian Sonia Kallick, author of “Lemont and Its People,” and her physician-husband Charles. Overwhelmed by the work, Yasko hired her artistically inclined parents Walter and Jo Nelson of Caledonia, Wis., as her full-time assistants.

Volunteers also helped paint. One was the Kallicks’ 12-year-old daughter Ingrid.

“Everything was mythical and magical,” says Ingrid Kallick, now 58 and a Philadelphia artist who returned to assist Yasko this year. “I thought, ‘Not only does this person like art, but they put it on a big public wall.’ It raised a curtain on a whole new world of art appreciation.”

When Yasko repainted the mural in 2000, she remade the face and hair of the woman on the wall to resemble Sonia Kallick, who had died three years earlier.

When Ingrid Kallick worked on the mural in September, she refined her mother’s portrait.

“My mom was the most interesting person in the whole world,” she says. “I was intimidated but honored to do it.”

Yasko was a protégée of pioneering South Side street muralist William Walker, who recruited her into the burgeoning mural movement.

Yasko’s “Under City Stone” is believed to be the first major community mural directed by a woman in Chicago and is among the longest surviving outdoor murals done by a woman in the United States.

She went on to lead work on five more murals in Chicago, including “Roots and Wings” and “Razem,” both which partly survive, before she and her late husband Richard, a University of Wisconsin professor, moved to Whitewater, Wis., in 1976. Her “Prairie Tillers Mural” in that city has been declared a local landmark.

Several years ago, Yasko recruited University of Wisconsin art student Harrison Halaska to be her main assistant on mural renovations.

“It’s so different than working in my basement,” says Halaska, a Lebanon, N.H.,-based painter and art instructor. “To be exposed to a community, working with a community and learning about a community — it’s just completely different from the more isolated side of painting. There’s a larger vision here.”

Yasko has had a lifetime of larger visions.

“I’m marveling at how I’ve spent an entire career working with the public,” she says. “If I can make a change or an impact on anybody in a community or town by contributing what I know, I feel that’s one way I can participate with society on my level, as an artist, in making this a better world.”