The weight of the roughly $80,000 in debt that Judith Ruiz would leave school with didn’t hit her when she was applying for the student loans that would finance her education at Columbia College Chicago.

Or while she was sitting in lecture halls. Or even as she walked across the stage at graduation.

But six months later, still without a job, with lenders hounding her to pay, her student loans caught up to her, and Ruiz defaulted — for the first time.

When she graduated in 2010, a year after the official end of the Great Recession, Ruiz had a hard time finding a job in her field — broadcast journalism.

The economy has rebounded. But the student loan debt burying Ruiz and others has soared to an all-time high. More than 44 million Americans now carry more than $1.4 trillion in outstanding student loans, according to an estimate by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In 2008, that number was $640 billion.

And experts say the number is sure to keep growing. Some liken the situation to the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, which caused housing prices across the country to decline.

Ruiz, now 30 and living with her mother in Oak Park, is working. But she remains in default on her student loans. And that’s eating away at her.

“My mother didn’t raise me to steal, and that’s what it feels like I’m doing,” Ruiz says. “I went to school. I got my degree. I have a full-time job. But I still feel like my mom didn’t raise me to take out a loan and not pay it back.”

Like many who started college and graduated around the Great Recession and find themselves mired in student loan debt, Ruiz has been putting off bigger things.

Their dreams of owning a home, having kids and some day having money to retire take a back seat as their debts make borrowing harder and delay their efforts to save and invest for the future.

After the recession, homeownership rates for 30-year-olds fell dramatically, from 32 percent in 2007 to 21 percent by 2016, according to a report last year by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. It found that, between 2003 and 2011, there was a roughly $5,700 increase in per capita student debt. And it estimated this increase could be responsible for as much as one-third of the decline in homeownership for those between 28 and 30 years old.

As of December, outstanding student loan balances totaled $566 billion more than credit-card debt, according to Federal Reserve statistics. The loans trail only mortgages as the most common household debt.

The delinquency rate — the percentage of loans that are 90 days or longer past due — hit 9 percent last year. That was the highest for any type of household debt at the end of 2017, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The rise in student loan borrowing tracks with the rising bite of college tuition. Average tuition and fees at public, undergraduate, four-year institutions rose by 156 percent between the 1990-1991 school year and 2014-2015, a report by the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College found.

Before then, college costs amounted to a little over 6 percent of median household income before room and board. By 2014, that number was nearly 16 percent.

As the price of college rose, wages stagnated in the 1990s. When the Great Recession hit, more people went back to college, taking out loans, in hopes they’d come out with the credentials to land better jobs. Add to that state cuts in aid for students, and taking out bigger loans to finance a degree became more commonplace.

“Year after year, we have slowly shifted more and more college costs onto the backs of students,” says James Kvaal, a former White House policy adviser who is president of the not-for-profit Institute for College Access and Success, which works to make college more affordable. “And we’re now seeing signs that, for many students, the debts are becoming insurmountable obstacles to getting ahead in life.

“These are people who played by the rules, worked hard, studied hard and are trying to make a better life for themselves — but, after college, in some cases, it doesn’t pay off, and they’re left carrying these debts they can’t afford.”

Not making payments on student loans can have dire consequences. Credit is damaged, making it harder to borrow to buy a home or car. Lenders can garnish wages. It could even mean the loss of professional licenses. And it’s nearly impossible to escape these debts through bankruptcy.

And, as bad as the impact was of the subprime mortgage crisis, there’s a big difference with what’s happening with ballooning student loan debt, says Marshall Steinbaum, a co-author of the Levy report.

“With student loans, there’s nothing to put back on the market,” says Steinbaum, research director at the Roosevelt Institute, a think tank. “You end up in a situation that’s just misery lasting for decades.”

Like Judith Ruiz, more people living with the weight of their student loans have moved back in with their parents — roughly 34 percent of 23- to 25-year-olds lived with their parents in 2004, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York research. By 2015, that figure had risen to about 45 percent.

“When I was younger, like 10 years ago, if you told me I would still be living at home when I turned 30, I would’ve said, ‘No, you’re crazy,’ ” the Columbia College grad says. “But a lot of my friends are the same way, and they’re all between 28 and 34. They all say they’re stressed. None of us see an end to this. If I didn’t have student loans, I could be doing so much more with my life. But I try not to dwell on it.”

Ruiz and other college grads still paying off their student loans interviewed by the Sun-Times all say they are putting off life’s milestones because repaying their loans takes so much of their income.

Rick Ceniceros, 27, left Columbia College Chicago in 2013 with a bachelor of fine arts degree in television and tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt.

Ceniceros, who lives in Garfield Ridge on the Southwest Side, says he’s making payments of nearly $130 a month under an income-based repayment plan. But that has barely chiseled away at his $47,000-plus in loan debt.

“The repayment plan is helpful,” Ceniceros says. “But when I started shopping for a house, there was a bank that I was trying to get a loan with that said I was not going to be able to get one because they don’t take the income-based repayment plan into account, and I had too much debt for them.”

Millennials are delaying homeownership, on average, by seven years because of their college debts, according to a report by the National Association of Realtors and the nonprofit group American Student Assistance. That same report found that about half of those responding said they had delayed continuing their education or starting a family because of their student debt.

Deshoun White, 26, says it took him two years to find a decent job after graduating from Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville in 2015 with a bachelor’s degree in marketing. He owes roughly $34,500.

“It should be manageable,” says White, who lives in Edgewater and has worked in marketing. “But when you think about how much money you owe, I feel like I was starting off from behind financially.”

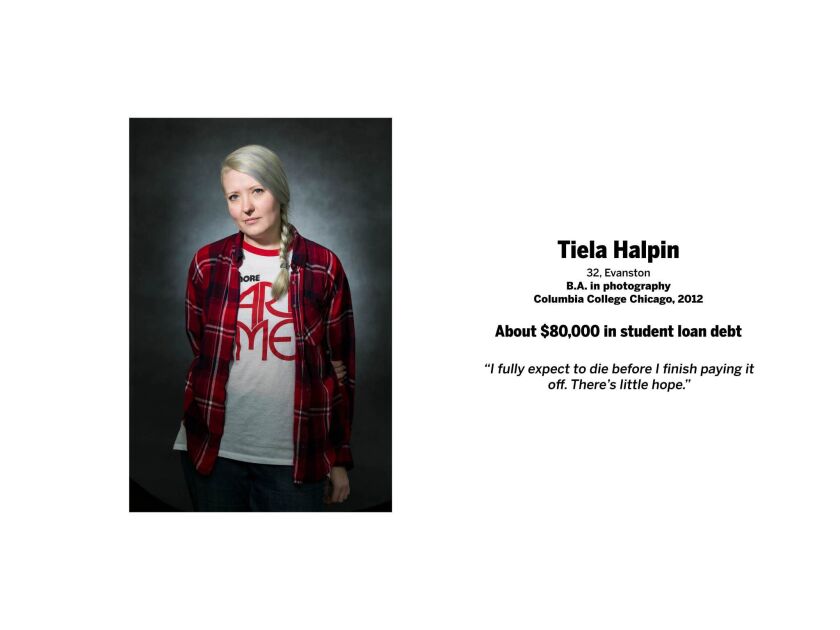

Tiela Halpin’s “college adventure” encompassed two majors, two colleges and six years before she was able to complete her bachelor’s degree in photography at Columbia College. Transferring from Monmouth College, switching majors from education to photography and the extra time that kept her in school left the 2012 grad, now living in Evanston, with roughly $80,000 in debt.

Even juggling three jobs, she says she struggles to make her monthly payments and sometimes has to choose between paying her rent or making payments on her loans.

“I’ll probably never be able to buy a car,” Halpin, 32, says through tears. “I can’t afford to have kids — maybe not ever, but not now. I joke about it with my friends. But it’s not entirely a joke when I say I fully intend to die with this debt. I don’t think it’s ever going to leave me.”

Amanda Spizzirri, 23, graduated from DePaul University last year with a bachelor’s degree in peace, justice and conflict studies. She owes $90,000 on her student loans — $30,000 of that in her name and $60,000 in “parent-plus” loans. Now living in North Center on the city’s North Side, she works multiple jobs, mostly in food service, in an effort to make her payments.

“Currently I’m working as a server and as a barista,” Spizzirri says. “And I walk dogs in my free time — all to try and make a little bit of money back.”

She dreams of being able to find a career, possibly working in criminal justice reform, where she can cause social change.

“I feel like my misconception was that taking out debt would help me pursue my dreams, but it’s actually inhibiting me from pursuing them,” Spizzirri says.

Jessica Barazowski graduated from Loyola University Chicago in 2015 with a degree in biology. Yet, even working as a lab technician and also in a veterinarian’s office, the 29-year-old Humboldt Park resident says it’s tough making the payments on her student loans.

She has roughly $100,000 in debt. Last year, she paid $6,000 in interest alone.

“How am I ever going to be able to afford a house,” Barazowski says. “Every day is a struggle just to afford living, getting to work, getting food and paying other bills, like gas or rent.

“I’m the first college graduate in my family, and I’m worse off than my two siblings who didn’t go to school.”

Bills have been proposed in Congress — and died there — to provide relief for those carrying the burden of heavy student loan repayments.

Mamie Voight, vice president of policy research for the Institute for Higher Education Policy, says the steep rise in student borrowing represents a “failure to address growing inequality in the education system. Low-income students are more burdened by college costs than their well-off classmates. But all students should have access to education and success.”

Voight says more federal funding for Pell Grants and other financial awards for low-income students might result in fewer students needing to take out loans.

John Rao, a lawyer with the National Consumer Law Center, says reopening bankruptcy protections for student loans should be part of the policy solutions to help those drowning in their debts.

Changes in federal law related to bankruptcy discharges for student loans have made it more difficult for borrowers to find relief, Rao says. Amendments to the Higher Education Act in 1998 and 2005 have made it harder to discharge student loans through bankruptcy. Now, to have those debts discharged, borrowers have to prove they represent an “undue hardship.”

The federal Department of Education sought public comment this year on what “undue hardship” means to “ensure that the congressional mandate to except student loans from bankruptcy discharge except in cases of undue hardship is appropriately implemented.”

“We encourage people to take on debt and then don’t provide a safety net when things go wrong,” Rao says. “Our view on bankruptcy is that it’s not to be abused — and it should be available when you’ve fallen on hard times. To not have that available for borrowers when we encourage them to take out loans doesn’t make sense.”

According to projections by Steinbaum and his co-authors on the Levy Economics Insitute report, canceling existing student loan debt could boost the U.S. gross domestic product by $86 billion to $108 billion per year.

Ruiz — who defaulted again on her loan payments in late 2014 — is still trying to dig herself out of debt even though she now has a job in public relations with the Better Business Bureau of Chicago & Northern Illinois. She doesn’t regret going to school and still believes her college choice was a good one. But she says that, if she somehow had the chance to go back in time but still know what she knows now about the true cost of her student loans, she might have done things differently.

“I would’ve educated myself before enrolling in college and become well-versed in what it means to take on that type of financial loan,” Ruiz says.

“It’s your first big investment, your first big decision before you even become an adult. And I feel like 17- and 18-year-olds coming out of high school need to be educated on that.

“You think, ‘Oh, hey, I’m just going to take out a loan, and it’ll cover everything, and I’ll just worry about it later,’ like a credit card. But this is so much bigger than that. That may work for a few thousand dollars, but it’s not going to work for $80,000.”

Rachel Hinton and Ashlee Rezin both have outstanding student loans, Hinton owing roughly $75,000 and Rezin $90,000.