John Singer Sargent famously studied in Paris, lived much of his life in London and had strong connections to the three principal art centers in the United States at the turn of the 20th century: New York, Boston and Philadelphia.

Much less known are the famed American painter’s abundant ties to Chicago — a multifaceted story that is told in a major exhibition opening July 1 and running through Sept. 30 at the Art Institute of Chicago.

‘John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age’ When: July 1-Sept. 30 Where: Art Institute of Chicago, 111 S. Michigan Tickets: Free, with regular museum admission Info: artic.edu

It is the museum’s first in-depth examination of Sargent in more than three decades — a gap that surprised Annelise Madsen, the museum’s assistant curator of American art, because of the artist’s stature and his many connections to the institution.

“One of the goals of the show is to introduce — or re-introduce — Sargent as a painter to our visitors,” she said. “Very purposefully, I wanted to have a show that looks at the breadth of his career, and we’re able to do that through the lens of Chicago.”

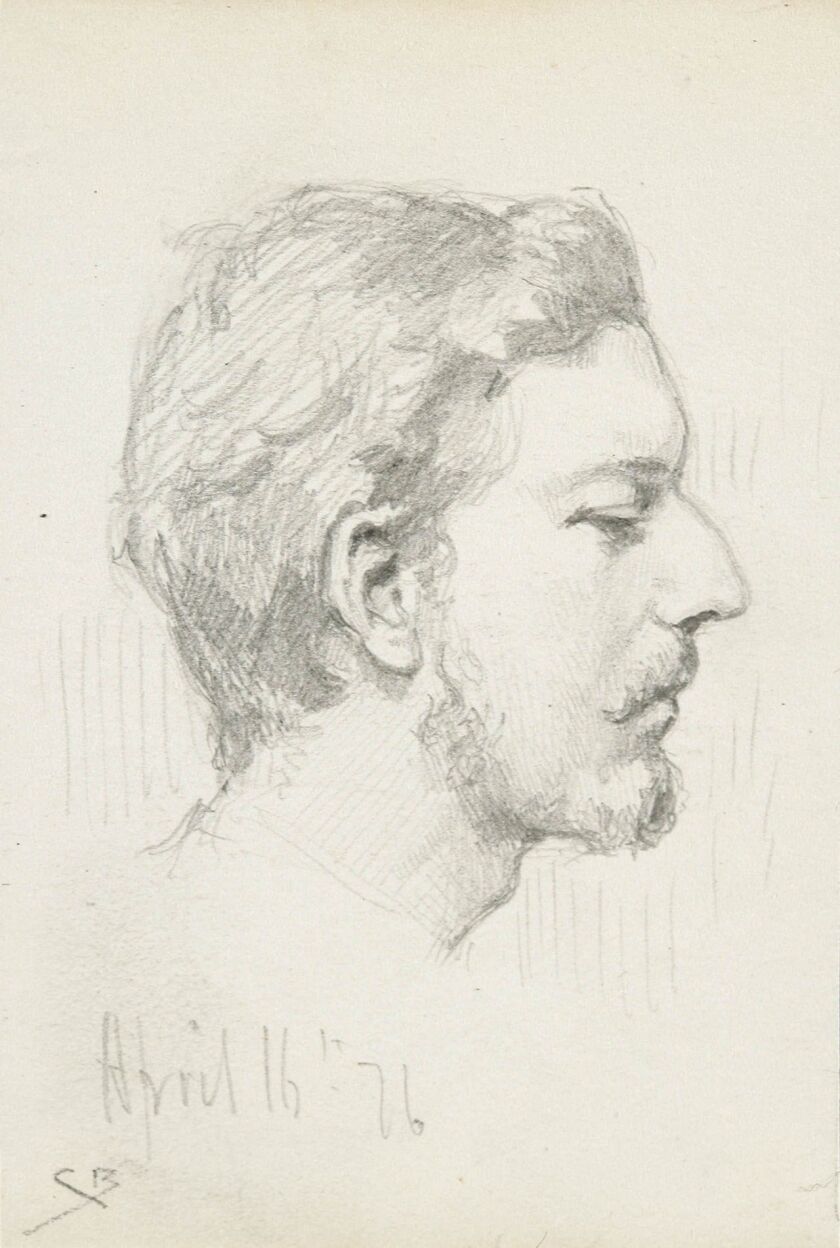

Sargent (1856-1925) is best known as a portraitist who painted hundreds of opulent likenesses of the rich and famous of the Gilded Age, but he also created a range of other works as well, including genre paintings, public murals and plein air landscapes.

“John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age” uses the celebrated artist as a touchstone to explore the city’s transformation at the turn of the last century into not only a booming commercial nexus but also a rising cultural center that could compete with those on the East Coast.

Two big steps in that direction came in 1893 with the World’s Columbian Exhibition, which city leaders managed to steal away from New York with some aggressive fund-raising, and the opening of the Art Institute in December.

Although Sargent only made two fleeting visits to Chicago, his works were showcased in more than 20 exhibitions in the fast-growing metropolis from 1888 through 1925 and acquired by local collectors like businessmen Charles Deering and Martin Ryerson.

Many of those pieces are featured in this exhibition, such as “La Carmencita,” a bold, full-length portrait of Spanish dancer Carmen Dauset, who created a sensation when she was on tour in New York and posed for Sargent in 1890.

Before the painting, now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, traveled to Europe, Sargent included it among the three works he sent to the Third Annual Exhibition of American Oil Painting at the Art Institute. It became an immediate hit with Chicago viewers.

“Her pose,” Madsen said, “and the daring way that Singer paints her, that kind of assertiveness of the figure speaks to the moment in terms of Chicagoans looking to put the city on the map in terms of culture.”

Other key works include “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), a portrait that secured his reputation in London, and “Three Boats in Harbor, San Vigilio” (1913), a seascape that has not been on public view for more than 100 years.

In all, the show features 95 paintings, watercolors and charcoal sketches and one sculpture. About two-thirds are by Sargent and the rest were created by artists in his trans-Atlantic circle who also had Chicago links: Cecilia Beaux, William Merritt Chase, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, James McNeill Whistler and Anders Zorn.

“Part of the exhibition is to show the great variety of his talent,” Madsen said, “but the second thread is looking at Chicago at this specific historical moment and thinking about this city on the make in the years after the Great Fire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Sargent fell out of favor in the middle of the 20th century with the rise of abstraction. But his stock has steadily risen in recent decades, aided in part by the 1998-2018 publication of a multivolume catalogue raisonné or authoritative inventory of the artist’s complete works. “I think Sargent is having a moment again,” Madsen said.

This exhibition emerges from recent scholarship that has shown Sargent as a more complex and progressive artist than previously thought. “We can see him,” Madsen said, “as an artist who was academically trained and part of a long line of art that comes out of the old masters but also see his Impressionist and more modernist leanings. He’s not old or new, he’s both of those things, depending on what he was working on.”

Kyle MacMillan is a local freelance writer.