The federal safety inspectors who are supposed to protect kids from dangerous toys weren’t standing guard for nearly six months while this year’s holiday gifts entered the United States by the shipload, a USA Today investigation has found.

Princess palaces and playhouses, water guns and tricycles landed on store shelves and front doorsteps without the usual safety checks for lead, chemicals or choking hazards because federal government leaders had secretly sent home the nation’s toy police.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission pulled inspectors from ports in Chicago and elsewhere in mid-March because of the threat to them of COVID-19.

The federal agency made the decision in private, keeping it secret from consumers and without full disclosure to Congress, then continued the shutdown at the ports and at a government testing laboratory until September — months that were inspectors’ busiest last year.

The watchdogs are supposed to intercept bad toys and other household products before they can be sold.

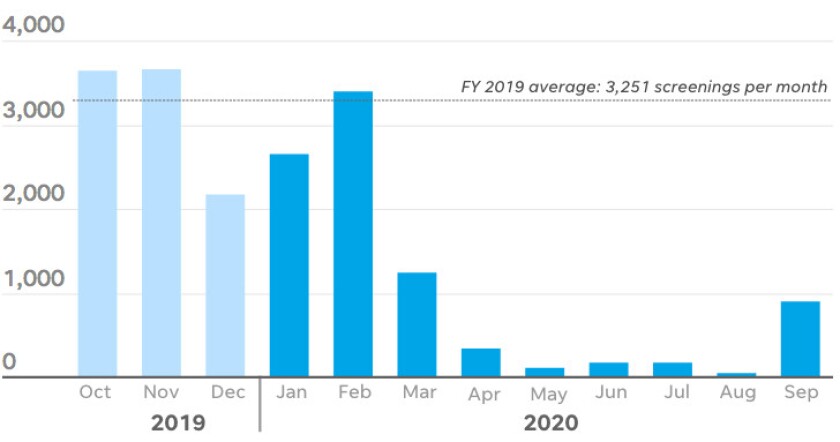

Yet the CPSC didn’t flag a single toy at the ports between June and July for poisonous lead levels, one of the most frequent violations, records show. In August, port inspectors reported total monthly activity of 47 screenings for all hazards — less than 2% of a typical month prepandemic.

As of this month, records show inspectors still weren’t working in five of the 18 ports they normally patrol, including Chicago.

And the CPSC failed to disclose how few violations it was catching. After January, it stopped posting that information online, updating that list only recently, after requests from USA Today.

Records and internal documents show that even after returning to the ports and reopening its testing laboratory, the CPSC still has identified fewer violations than usual for serious threats. Violations that saw a dramatic drop-off in September vs. a year ago include toys with small parts that can choke toddlers and children’s products with hazardous levels of chemical phthalates.

CPSC safety screenings fell by half

Each month’s total is the difference between the year-to-date total in that month’s report compared to the year-to-date figure the previous month. The total for September, when the fiscal year ends, is the fiscal year total from the annual report subtracted from the August monthly report total. This is based on a USA Today analysis of internal U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission data.

Carlie Procell / USA Today

Experts fear it could take years to discover the dangers allowed into American homes.

National retailers and distribution companies have imported tens of thousands of shipments during the pandemic. The retail industry says it doesn’t rely on the CPSC to keep consumers safe. Importers and manufacturers are required to monitor their own products and inform the government of hazards.

Robert Adler, acting CPSC chairman, said broadcasting its port playbook would have invited companies to exploit the system and that the decision prioritized employees’ health.

Adler said the agency sought help from customs and border patrol agents but didn’t give specifics.

“We stopped a fair amount of stuff,” he said. “We didn’t stop all of it. But we never stopped all of it.”

The CPSC informed Congress, Adler said, though some lawmakers say it didn’t reveal the extent to which it had abandoned its port duties.

U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Connecticut, ranking member of a subcommittee overseeing the consumer agency, said he was unaware of the CPSC’s dormant months until contacted by reporters. He plans hearings to demand an explanation.

“The total lack of inspections is absolutely inexcusable,” Blumenthal said, “especially because of the concealment.”

Meghan DeLong knows firsthand how much parents depend on government safeguards. In 2017, her 2-year-old son Conner died after an IKEA dresser tipped over on him. She blamed IKEA, which has recalled some faulty dressers though not the model that fell on Conner.

The Florida mother fears her 5-year-old and 7-month-old sons now face a risk from their toys., saying “it’s actually terrifying to know that something being used with our most innocent and vulnerable populations has not been through screening.”

The CSPC’s port investigators call themselves the toy police. Normally, 32 investigators work in a dozen states and Puerto Rico, opening shipping containers and running electronic screeners to detect lead and phthalates above legal limits. A tube as thin as a toddler’s throat identifies toy parts small enough to kill.

The CPSC does more than screen toys. Congress created the agency in 1972 to set and enforce safety standards for everything from cribs to lawn mowers.

Nearly four in five recalls involve imported products, according to the agency.

The CPSC spot checks to screen for hazards that wholesalers and retailers are supposed to test for themselves. It tracks risky products, such as those from importers with a history of violations.

During coronavirus-related closings from April to September, the agency issued one-fourth of the violations it did in that period a year earlier.

Lead violations at the ports plummeted from a monthly average of 50 to zero last spring. Lead poisoning is a hidden hazard.

“You won’t necessarily know that your child has been exposed,” said Dr. Gary Smith, director of the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio. “We really do depend on the Consumer Product Safety Commission to protect kids.”

The CPSC and industry groups say these safety measures aren’t optional even during a pandemic.

“We still expected companies to engage in recalls of their products,” Adler said.

Large wholesale distributors, shipping companies and name-brand retailers — including Target, Dollar Tree, Walgreens, Amazon and UPS — were among those that brought in products from overseas while the watchdogs were away, according to shipping data maintained by the trade research firm Panjiva.

Items imported by each of those companies have been flagged for violations by the CPSC more than once in the past seven years, records show.

Of 10 name-brand companies with past violations, those that responded to questions said their products are safe because they kept on screening.

“Changes in port staffing have absolutely no impact on Target’s product safety standards,” spokeswoman Jenna Reck said.

The Retail Industry Leaders Association, which represents many major stores the CPSC regulates, said the agency didn’t inform it of the pullback.

In recent years, the agency most often has cited companies that aren’t U.S. household names. Experts and retail industry representatives warn that online retailers use third-party distribution companies that could lack the kind of safety standards consumers expect from brick-and-mortar retailers.

From spring through early fall, more than 100,000 shipments with toys passed through American ports, according to the Panjiva data.

Internal emails and documents show Adler, a Democratic appointee, and Mary Boyle, CSPC’s executive director, knew their decision to implement remote working was risky.

CSPC commissioners were asked to email their feedback.

“My only concern is moving port staff away — we will have no defense to incoming crap,” Commissioner Dana Baiocco wrote on March 16.

After conversations with agency staffers, Baiocco emailed a dozen CPSC officials again, saying she was comfortable with plans to keep working remotely.

“I think given the choice,” she wrote, “we should take care of our people.”

Commissioner Peter Feldman noted other agencies planned to continue port operations but said he worried about “CPSC being blind at the ports.”

DeWane Ray, deputy executive director, said the agency “essentially would go dark on targeting and holding shipments” and conduct “in-depth investigations over the phone.”

“There will be limitations to that,” Ray acknowledged.

Adler said on a call that day that nothing so far had been very worrisome.

Yet port inspectors had identified significantly more lead violations between January and March 2020 than in the same period the year before, according to violation logs, and was on track to find nearly 200 more port violations for the year — from lead to choking hazards — than in 2019.

Asked about lead hazards that might have been missed during the pullout, Alder said kids are more likely to be harmed by toxic paint peeling off walls in older homes or playing near former chemical dumping grounds.

“Lead in toys is not the biggest lead hazard to kids by far,” he said.

In March, on the private call with commissioners, the agency’s executive director also said she thought problems could be chased later, meeting notes show: “Although not ideal, we can always do things after the fact with recalls even if we can’t stop things at the port.”

Safety advocates say that’s a dangerous strategy. It can take years for the CPSC to identify products harmful enough to recall, and it has struggled to inform consumers and get them to return products.

“Recalls are not a good solution,” said Nancy Cowles, executive director of Kids in Danger, a safety organization based in Chicago whose focus is children’s product safety. “It’s like saying you find something in the autopsy. It is a little too late to be helpful.”

Rachel Weintraub, legislative director for the Consumer Federation of America, urged the government to get back to normal port inspection levels. She said the CPSC also can send investigators to check products already on store shelves.

Children’s toys and other items are especially worrisome to safety advocates because they often are passed along to siblings and other families or resold at thrift stores.

Adler and his chief of staff Sarah Klein said they’ve kept Congress informed, providing a letter sent March 19 to the ranking member of the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee explaining the agency had “implemented policies to direct all telework eligible employees to work from home on a full-time basis.” But it didn’t say port employees were pulled.

An email to staff three days earlier was more direct: “CPSC employees working at the ports are instructed to perform all duties from their home worksite.”

Adler said the agency alerted the public with communications such as notices on its website that recall remedies might not continue as usual.

He said he weighed the harm that could come were companies to know its blind spots and asked, “Why would we tell consumers?”

It took months till U.S. Sen. Jerry Moran, R-Kansas, chairman of the Senate committee that oversees the consumer protection agency, learned of the ports slowdown, according to his staff, which wasn’t told the extent of the withdrawal or its impact.

Moran recently co-wrote legislation to make the agency study any products that hurt or killed kids, seniors and minorities during the pandemic.

U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky, D-Illinois, who chairs the House consumer protection subcommittee, said her staff was generally aware the CPSC scaled back but isn’t satisfied with the agency’s explanation of why it kept port investigators away so long.

“A completely inadequate response,” Schakowsky said. “CPSC is not doing its job.”

The agency kept field workers home long after stores reopened, filled with shoppers buying products that might have lacked the usual safety checks.

Its commissioners had been told the agency planned to get work done by enlisting Customs and Border Protection agents still at the ports, according to notes from internal conversations in April. Agency bosses hoped for assistance at seven ports — fewer than half of those the agency normally covers.

What happened to that plan is unclear. The CPSC didn’t respond to questions about it but said border patrol agents sent samples to port staffers at their homes. Field staffers did virtual investigations, and the agency kept processing recalls of products flagged by companies, spokesman Joseph Martyak said.

Border Protection officials didn’t respond to questions.

Corporate consultants said the CPSC called importers during the pandemic to ask them to self-report substandard items, a practice long used to augment its surveillance.

At the beginning of the year, its inspectors performed an average of 3,000 monthly screenings at the ports. By May, that number had plummeted to about 100 and in August to just 47.

The agency tied its return to the field to strict COVID-19 criteria under a plan that placed Boyle, the executive director, in charge of decisions. Records show that some thought an appointed officer like Adler should have that responsibility.

In a May email chain, Feldman warned Adler against delegating.

“Accountability should rest with a PAS,” he wrote, referring to presidential appointees requiring Senate confirmation. “It would be inappropriate to abdicate these functions.”

The CPSC’s leadership responsibilities quietly had been shifted in late 2019. An order signed by Adler’s predecessor Ann Marie Buerkle consolidated operations under the executive director, who isn’t a political appointee, delegating authority away from the chairman.

Buerkle had been criticized for the agency’s lethargic response to products that caused deaths and grave injuries, from jogging strollers to inclined infant sleepers.

The Sun-Times’ Aug. 7, 2019, report on dangerous inclined infant sleepers.

Adler rejected the proposal for the chairman or full commission to decide on the COVID-19 reentry timing.

Feldman urged him to inform Congress: “I’m sure they’re unaware and operating under the assumption that you’re running point on COVID response and reentry.”

It wasn’t until September that Boyle began clearing staff to return to ports and the lab, once scare protective equipment was secured, Martyak said.

Yet care packages the agency mailed out earlier in the summer included cloth face masks and mini-sanitizer bottles emblazoned with the CPSC logo.

By October, the ports in Los Angeles, which receive almost 40% of the country’s total container imports, were having their busiest months ever. CPSC regulators were returning to work — yet they still found only 61 violations at the ports. Most involved minor problems with toys, such as missing paperwork or poor labeling.

The agency didn’t issue any violations in September or October for pajamas that can easily catch fire. At the start of 2020, that hazard was flagged repeatedly.

Records show that, as of this month, the agency remained inactive at five port locations: Chicago, New York City, Savannah, Buffalo, New York, and Norfolk, Virginia.

Rising coronavirus rates around the country shouldn’t prompt the CPSC to pull back from the ports again, Adler said, noting that the agency now has more masks and other protective gear.

Read more at USA Today.