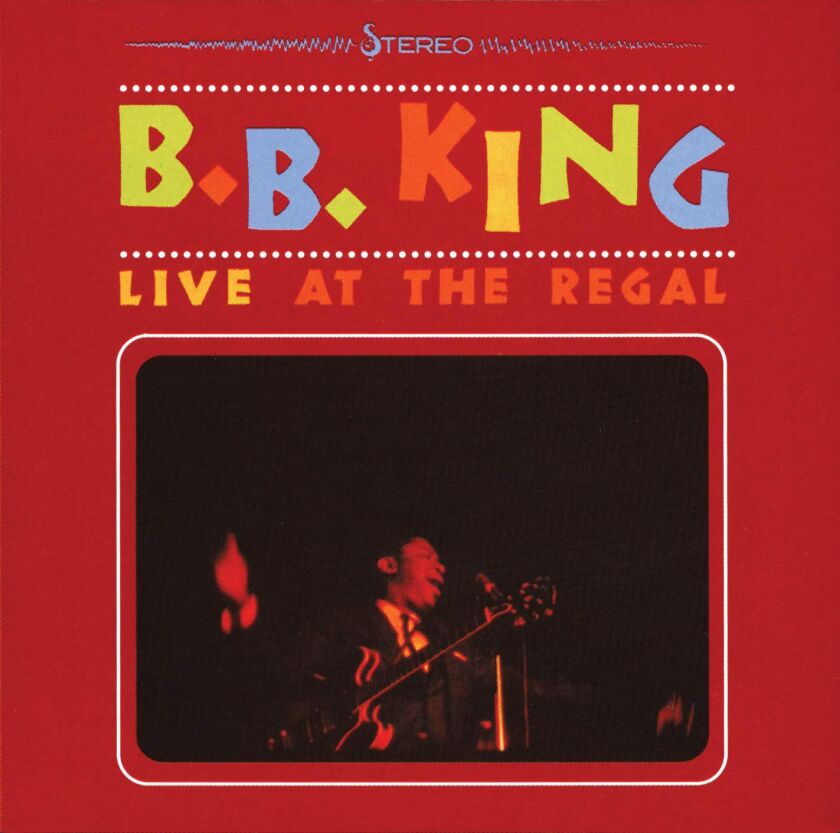

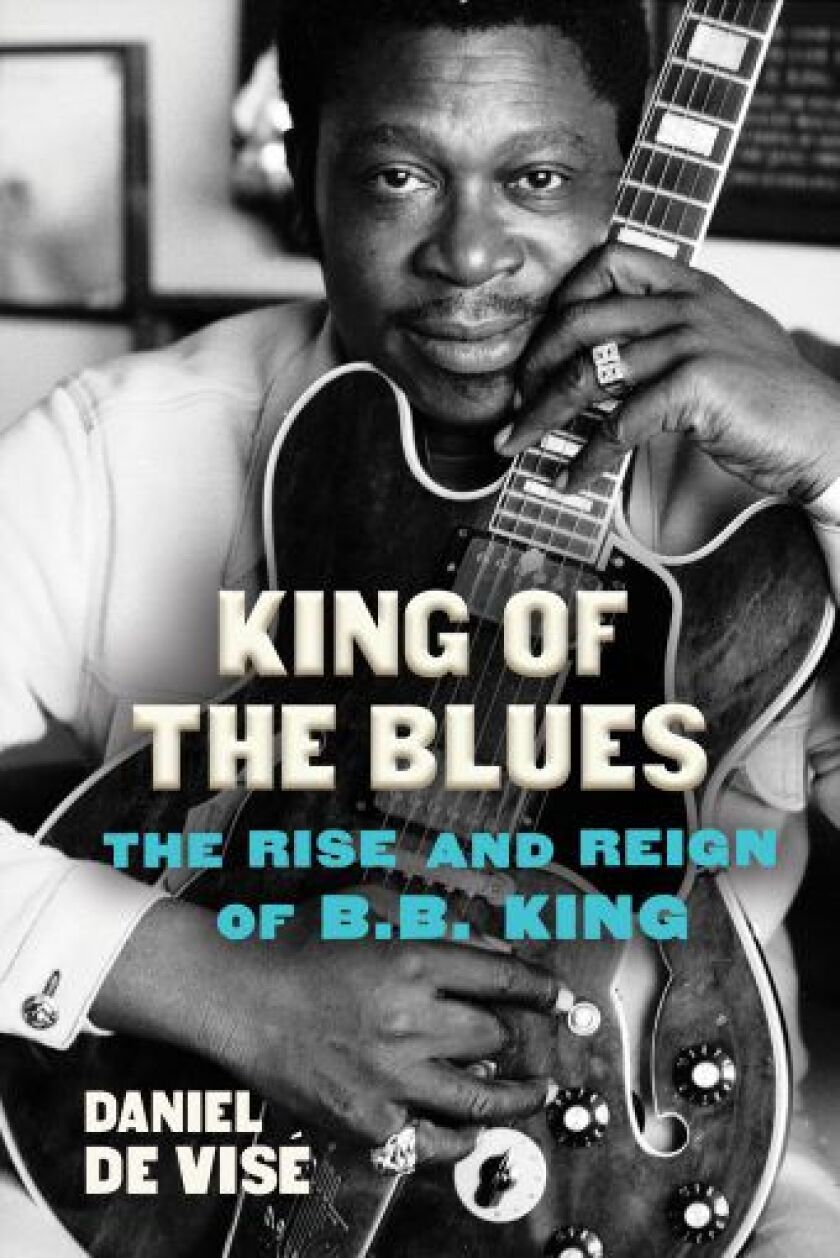

It was 57 years ago this weekend when B.B. King recorded one of blues music’s seminal records at the Regal Theater in Bronzeville. This recap of that night is adapted from Daniel de Visé’s new biography “King of the Blues.” (Grove Atlantic, $30)

In the autumn of 1964, B.B. King’s celebrated career seemed to be winding down. The King of the Blues felt anonymous on his corporate label, ABC-Paramount. His singles were barely charting. Frustrated executives turned to Johnny Pate, a fine producer who had teamed with Curtis Mayfield and his Impressions on a string of soul hits.

Pate conferred with King on how to turn things around. They decided the quickest way was to record something live, the sooner the better. Thus, sheer convenience inspired the most famous live album in recorded blues.

Chicago’s Regal Theater had opened in 1928, a gem in the necklace of chitlin’ circuit palaces. Little Stevie Wonder, child star of Motown, scored his first No. 1 hit with “Fingertips,” a vocal and harmonica workout recorded live at the Regal and featuring the audience as much as the singer. Pate saw similar potential for King.

The temperature dipped below 15 degrees on a frigid Saturday as patrons filed in to the Regal on Nov. 21, 1964. They didn’t know King’s sets would be recorded. Neither did the band.

Promoters padded out King’s combo with another full ensemble, the Regal house band. The last-minute addition of unrehearsed musicians seemed an odd choice at a gig to be recorded for posterity.

A sound crew set up beneath the stage. Legendary conductor Fritz Reiner had used the same gear to record his Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Technicians hung microphones high above the seats to capture the crucial interplay between King and his audience.

The Regal touted continuous shows running past midnight. King and his band probably played four sets that day as the headliner on a bill that included Mary Wells, of “My Guy” fame, among other acts.

Pate lined up deejays from Chicago’s premier Black radio station, WVON, to introduce King’s sets. Their participation encouraged airplay for King’s music.

In the first recorded set, preserved on side one of the resulting record, the announcer was Pervis Spann, a Mississippian from King’s own hometown of Itta Bena.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he cried, “how about a nice warm round of applause to welcome the world’s greatest blues singer, the King of the Blues, B.B. King!” In those days, King was known more for singing than guitar craft.

The band launched into a frenetic reading of “Every Day I Have the Blues,” and the audience exploded in rapture. Twelve bars in, Lucille, King’s guitar, made her entrance with a mellow and understated solo. Then King sang, his calm delivery counterbalancing the band’s harried pace.

Barely two minutes later, the song was over. “Thank you very much,” King said. He launched into the next number, playing a rising riff in the odd key of D flat that his bandmates instantly identified as “Sweet Little Angel.” Somehow, the Regal house band caught on.

The crowd was warming. One young woman cried, “Come on, B.B.,” amid scattered screams. Lucille led out the song for nearly a full minute before King sang the opening line, his voice rising to a sensual growl as he lingered on the words “I love the way-ay-ay she spreads her wings.” The screams became a chorus. Some fans swayed in full delirium.

Daniel de Visé’s recap of the night 57 years ago that B.B. King recorded one of blues music’s seminal records at the Regal Theater in Bronzeville is adapted from his new biography “King of the Blues.”

Grove Atlantic

“Live at the Regal” reached its dramatic peak on the fourth cut, “How Blue Can You Get.” King calmed the audience to a polite hush in the opening stanzas. He could command an audience the way Reiner had led the CSO. Their communion provided the dramatic arc to this recording. King approached the climactic section of “How Blue Can You Get” with the band and its listeners reaching simultaneous crescendo. When King roared the payoff couplet, “I gave you seven children/ And now you wanna give ’em back,” the room exploded in a single, cathartic cry.

When the show was over, patrons poured out into the frigid Chicago night, many voices hoarse from their exertions.

“Live at the Regal” would become a textbook for generations of future rock and blues guitarists.

But King and his bandmates never cared for it: To their ears, the mashup of bands yielded a sloppy mess.

“It sounded like s- - - to me,” sideman Duke Jethro recalled.

They preferred “Blues Is King,” King’s next live set, recorded in November 1966 at another Chicago venue, known simply as The Club.

Six decades on, both discs endure as blues classics.