Communication theorist Marshall McLuhan famously said, “The medium is the message.” With Barbara Kruger, it is more the message is the medium.

For more than 40 years, the influential artist has used and re-used pithy and pointed phrases to question mass media and consumerism and examine issues of power and identity in a dizzying variety of mediums, from “pasteups” and video installations to magazine covers, tote bags and skateboard decks.

Even people who have never heard of Kruger have likely seen her work or echoes of it. Her instantly identifiable style, including her use of eye-catching, white-on-red text and bold, unadorned typefaces have influenced the graphics of companies like the lifestyle brand Supreme.

The Art Institute of Chicago will pay tribute to Kruger’s broad-ranging cultural impact with “Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You.,” the first museum survey of her work in the United States since 1999.

Opening Sunday, it runs through Jan. 24, then tours to the two other organizing institutions — the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York.

“It’s not a marquee name outside of the art world,” James Rondeau, the Art Institute’s president said of Kruger, who lives in New York and Los Angeles. “But general audiences will definitely gravitate to the content and recognize that signature graphic style and, more important, the voice. Barbara is channeling and distilling our culture at large in that anonymous voice that her work speaks from.”

While a significant portion of the show will be shown in the Art Institute’s principal temporary exhibition space, Regenstein Hall, her works also will be spread across the museum and spill into the community on billboards, bus stops, storefronts and elsewhere.

“Just the sheer coverage of her work both inside and outside the museum — we’ve never done anything like this before,” said Robyn Farrell, associate curator of modern and contemporary art, who co-organized the exhibition’s presentation with Rondeau, the museum’s former chair and curator of contemporary art. “It will stop people in their tracks.”

“Thinking of You.” is deliberately not called a retrospective, the usual term for such a big, milestone solo exhibition, because it does not examine Kruger’s work in a decade-by-decade, career-building fashion.

Farrell calls it an “anti-retrospective.” While a little more than a third of the nearly 80 works on paper and vinyl, installations and videos in the exhibition predate the turn of the century, 48 were produced since then and 40 of those were made or remade for this show. These numbers do not include the other Kruger pieces spread across the city.

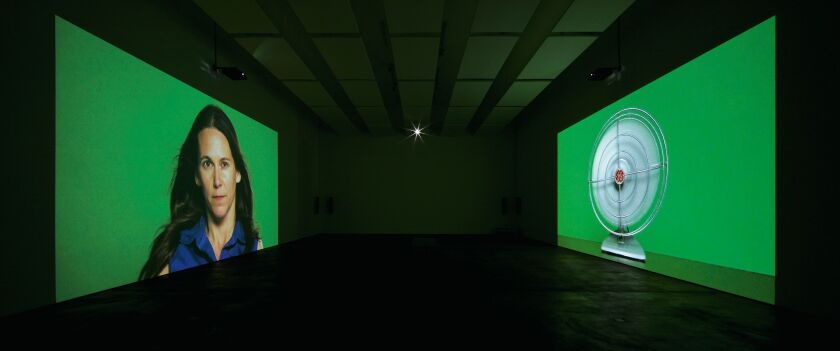

Adding a layer of complexity to or even confounding the usual chronological narrative, some of the artist’s recent creations rework or rethink previous works, adapting them to new technologies, such as the latest multichannel video platforms and altering to them to fit today’s sociopolitical climate.

“In this case,” Rondeau said, “Barbara herself is the engine of a critical reappraisal of her own. And so migrating those messages into the present tense, that’s what I think is absolutely amazing. And I don’t know that anyone has ever actually done this: just blow up the model of the retrospective and do that reappraisal yourself and migrate 1985 into 2021.”

Of particular note are five of what Farrell called “replays,” large-scale videos on LED panels in which Kruger references previous artworks. Among these is a 57-second work — “Untitled (I shop therefore I am)” (1987/2019).

“They are so powerful,” the curator said, “in the way that we say a phrase that we might know of hers, and we see how it can change be just as relevant and just as powerful as one of her iconic works from 30 years ago.”

The survey holds particular importance for Rondeau, who calls Kruger’s art a “personal passion.”

“Barbara’s work changed my life,” he said. “As a student, as a young curator, as a citizen, frankly I learned so much from it and have been shaped by her work.”

Beyond his own interest, he believes her work has widespread relevance to Art Institute visitors and society.

“She was the first artist that taught me that art can be an integral part, if not even an engine, for urgent public discourse,” he said.

He wants to resist falling back on the old chestnut that “never has it been more relevant,” but Rondeau believes that Kruger’s prescient work has as much, if not more, to say to people today as it did when she began in the 1970s.

“Sadly,” he said, “the things she said in 1979 still need to be said in 2021.”

Kyle MacMillan is a freelance writer.