The atrocities committed against indigenous people by white settlers are being acknowledged in Chicago and across the country, but the “Apsáalooke Women and Warriors” exhibit at the Field Museum isn’t about that.

“We’re looking at resilience,” said its curator, Apsáalooke scholar Nina Sanders (or Akbileoosh/Brings the Water, her name in the tribe’s Crow language). Rather than focusing on indigenous suffering, she said, “you’re sort of immersed in art and narrative and music.”

The exhibit is an exuberant display of Apsáalooke life and culture, both past and present. Ancestral historical artifacts are placed alongside new art by contemporary Apsáalooke creators, some of which was created specifically for the exhibit and includes sculpture, paintings, photography, beadwork, fashion and rap music.

But the exhibit also has a deeply reflective note, which can be chalked up to Sanders’ overriding ambition to “kick down doors” and step away from stereotypes.

Part of this is in response to how indigenous belongings and history have been treated in the past — the idea for the exhibit arose alongside plans to renovate the Field Museum’s previous Native American collection, which hadn’t been updated since 1950 and was, in Sanders’ words, “incredibly racist.”

Sanders came in as an indigenous advisor when the Field Museum was working with the University of Chicago on the Open Fields project, which pushed to change how Native historical objects are presented in museums.

“Conversation led to [people asking me], ‘What would you do, what would an exhibition look like to you?,’ ” said Sanders. The result was “Apsáalooke Women and Warriors,” the museum’s first large-scale exhibition curated by a Native American.

Running at the Field until April 4, 2021, the exhibit documents the history of the Apsáalooke, a Native American Plains tribe based in southern Montana. Sanders grew up on the Apsáalooke reservation speaking Crow as her first language, and the exhibition is told from her point of view through labels introducing each object.

Although Sanders said she has been generating this exhibit “my whole life,” it was also the result of work done with 18 Apsáalooke scholars, activists and creatives.

The exhibit is organized so that visitors walk around each section clockwise, following the journey of the Apsáalooke tribe.

“Clockwise represents renewal, life and birth,” said Sanders. “Sort of like the transition[s] of life.”

The exhibit starts with the creation story, shown in cartoon form on a screen at the start of the exhibit, that is followed by a section telling the story of migration and the Apsáalooke people’s search for meaning, which then expands into their “self-actualization,” followed by successes and spirituality represented by objects such as the war shields and war bonnet.

Along with telling the history of the Apsáalooke tribe, Sanders wanted to break down stereotypes about indigenous people. The feathered war bonnet is captioned “Not a Costume,” and the sacred shields are watched over by imposing black-and-white portraits of Apsáalooke women, as was traditionally done.

The exhibit also examines gender roles.

“We’re an egalitarian society,” said Sanders. This point is made clear in the very beginning, with a TV screen to the left of the entrance showing a cartoon of the Apsáalooke creation story narrated in Crow, which Sanders described as “the part that’s most important to me.” The cartoon shows that “women are equal to men, we were created at the same time,” said Sanders.

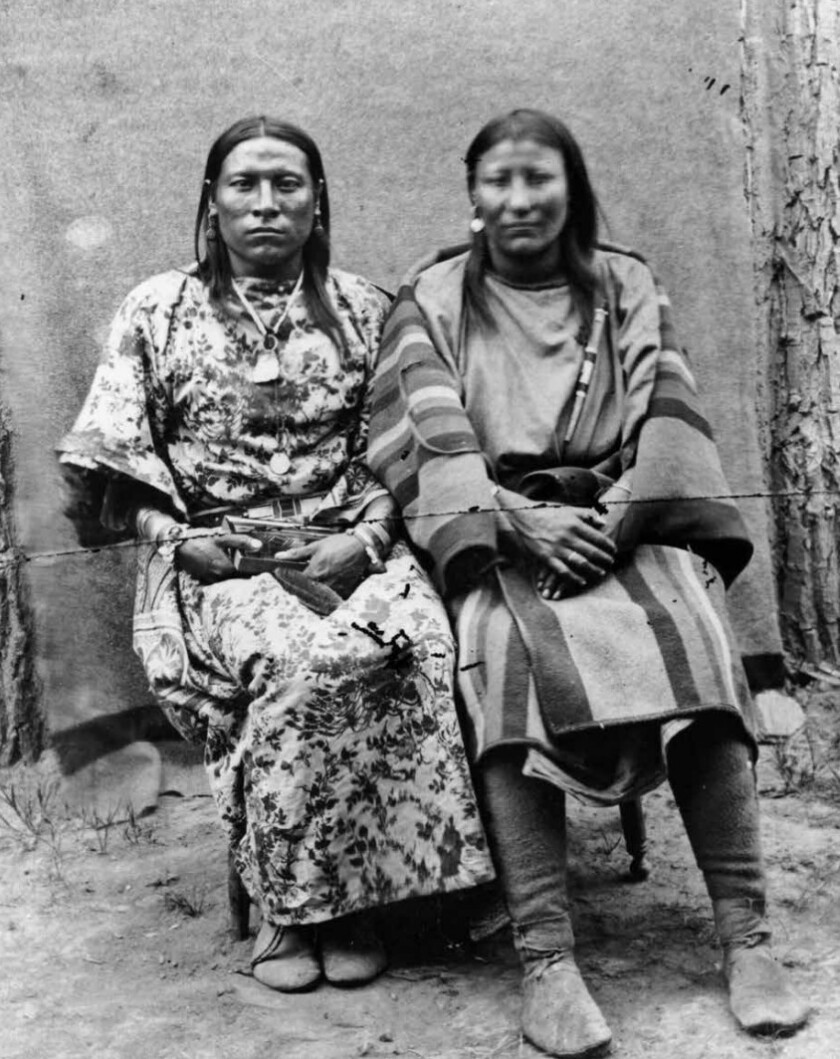

There is also an LGBTQ section that focuses on Apsáalooke views of gender — it centers around Finds Them and Kills Them/Ohchiish, an Apsáalooke person who identified as “batée,” which is taken to mean transgender or gender-nonconforming.

Another misconception that the exhibit addresses is how indigenous people are often seen as a relic of the past.

“Native Americans are still here [but] a lot of people don’t think that we still exist,” said Sanders’ relative Elias Not Afraid (Crow name Outstanding Young Man/Iisáaksh Xíassaash), an artist whose beadwork is exhibited alongside those made by his ancestors.

Sanders deliberately chose her relatives and friends to contribute to the exhibit. “It’s my duty to my people to lift up our visual arts,” she said, adding that “over all of the [contemporary] contributors, we only had three people, I think, who were over the age of 35.”

Among the works by young Apsáalooke artists are paintings and a sculpture by artist and activist Ben Pease (Crow name Steals the Guns from Two Enemy Camps/Aashdúuptakò Ishtaxxía Dúutchish), and music by Native artist Supaman, whose rap songs play overhead as the exhibit’s soundtrack.

The exhibit also intends to prompt questions about ownership.

Artist and activist Pease, who engaged in conversations around the creation of the exhibit, said it redefines “how institutional entities build relationships with indigenous communities,” and forces people to question what should be on display and how things should be displayed.

According to Sanders, this question extended to fragile historical objects that — according to the science of conservation — might be ruined by being displayed.

“There were places where we had to take controlled risks,” she said, when it came down to making sure that significant objects that highlighted important parts of her tribe’s history were seen.

The exhibit is also for indigenous people, said Sanders.

“It helps for Native people to participate in a healing process,” said Sanders. “I personally would like for an indigenous child to imagine themselves curating an exhibition, or talking about what a war bonnet means to them and how it should be properly used.”