Vicente Zambada-Niebla, whose testimony helped convict Mexican drug kingpin Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera, was given a 15-year prison sentence Thursday in Chicago, where prosecutors said his cooperation led to hundreds of arrests.

When he was indicted in Chicago in 2009, Zambada, known as “El Vicentillo” or “El Mayito,” was portrayed as a logistics mastermind for El Chapo’s Sinaloa cartel.

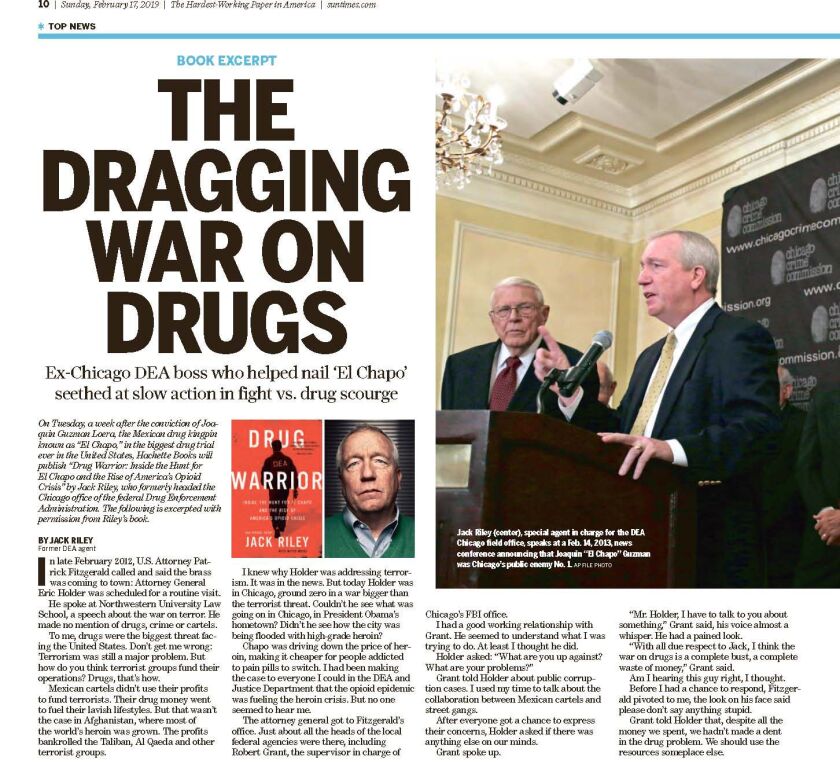

Jack Riley — the retired head of the Drug Enforcement Administration in Chicago who went on to be the DEA’s No. 2 official in Washington — has a different view of the onetime overseer of Chicago’s biggest drug dealers, twins Margarito Flores and Pedro Flores.

In “Drug Warrior: Inside the Hunt for El Chapo and the Rise of America’s Opioid Crisis,” published in February, Riley writes of Zambada’s “uselessness” as a witness against the cartel.

In this excerpt from Riley’s book, reprinted with permission from publisher Hachette Books, he writes of meeting Zambada after he was debriefed by agents and prosecutors in Chicago.

“Hey, boss, I want to run something by you,” my agent David Lorino said to me. “It’s Zambada. I think we’re going to be done with the guy in a couple of days. Do you still want to talk to him?” Jesús Vicente Zambada-Niebla had been shuttling between a federal cell in Michigan and a Chicago jail since being extradited to the United States.

Lorino had been the point man ever since, interrogating him and helping DEA agents from all over the United States get needed information from Zambada. Zambada was the son of Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada — Chapo’s right-hand man. “El Mayito,” or the “Little Mayo,” was a major trafficker in his own right. He was awaiting trial in a U.S. federal court in Chicago on cocaine and heroin trafficking charges. Mayito was one of a slick new generation of Mexican traffickers, dubbed “narco juniors.” The Justice Department said his extradition was one of the most significant in years.

El Chapo was Zambada’s godfather. So Zambada had been biding his time in jail. He said he’d talk, but first he had to speak to his father. It took a while to set that up. We had to give Zambada a cell phone, then give his phone number to his Mexican attorneys, who somehow got it to El Mayo. Then we had to wait for the call. Late one night, after most of our agents had gone home, Mayo called the number. We recorded it.

“My son, my son, how are you?” he asked. They chatted briefly. “I want you to know you have my authority to begin to cooperate, to get your life back,” Mayo said. That was it. The call lasted two minutes.

It looked like Mayo was double-crossing Chapo. That’s how I read it. But there was another fact in play: Mayo knew that enough time had elapsed now, that they’d changed their systems enough that anything the son said couldn’t really hurt the father or the godfather.

So after two years of delays, Zambada Jr. started talking. And so far, the stuff he gave us was too old to use. That just angered the hell out of me. He was playing us. Despite his uselessness, Lorino kept pressing Zambada. He’d often stop by my office and update me because he knew that I’d been tracking him and the cartels for two decades.

“You should sit in,” Lorino would say. “Dave, I’d just be a distraction. You guys don’t need me hanging over your shoulders.” But now the judge had set a trial date. I might not get another chance. This might be the closest I ever got to Chapo, so the hell with it.

“You know what? Let’s go see him now,” I said to Lorino.

He flashed a wide smile. “That’s what I thought.”

I called the U.S. marshals who were guarding Zambada in an off-site Chicago safe house and told them I was coming for a visit. Lorino and I walked there. On the way I thought of the questions I’d ask. Lorino and several others had already interrogated him. This was for me. For my own sake. I just wanted to look him in the eyes and see how reality stacked up to my expectations. Once there, the marshals led us into a small, dimly lit room, sunless as a basement apartment but bristling with surveillance cameras. I sat down at a tiny table with a DEA translator.

A few minutes later, a door opened, and a tall, gaunt man walked into the room. He was dressed in a purple velour tracksuit with gold chains dangling from his neck. He looked like a New York pimp from the 1980s. I stared for a moment. This was Zambada? He looked nothing like El Vicentillo, Pretty Boy Vicente, handsome drug capo, son of the powerful Sinaloa cartel. Really, this is the guy? You gotta be kidding! I thought. This is the son of Mayo, partner of Chapo, killer of innocents and destroyer of lives? This is it?

He walked to the table and reached out his hand to shake mine. I did not respond. I kept my hands folded on the tabletop. I wanted to grab him by his neck, but I didn’t do it. I was going to be professional, dammit. He was a little taken aback, but he sat down.

When he did, I stared straight into his eyes. He looked away. He was meek. A wimp. Without his guns and bodyguards, he was nothing. The translator told Zambada who I was. I said I wasn’t going to take much of his time.

“I just got a couple of questions for you,” I said, waiting for her to translate. “How are you being treated?” I asked.

The marshals and agents treated him well, he said. Pleasantries out of the way, I cut to my real thoughts.

“I gotta know something: Did you know I was in El Paso?” I asked.

He smiled and nodded his head yes.

Just what I thought.

“Well, could you explain to me how you could justify the violence and murders that you, your father and Chapo are responsible for?”

I had thought about that question for a long time, and I wanted to see his response. But there was none. He showed no emotion, made absolutely no movement in his body. He was normal, neutral, unfazed.

And then, through the translator, he said, “We were at war. We were at war for our families. We were at war for our territory. Sometimes there are casualties in war.”

There was an awkward silence. I felt myself flush red. I couldn’t believe it. All those lives — they meant absolutely nothing to this scumbag. I wanted to reach across the table and cold-cock the bastard. I didn’t do it. No, everybody was looking at me. I regained my composure.

I asked him, “How close and how often did you meet with Chapo?” “Well, I’ve been around him off and on my whole life,” he bragged.

Chapo was like family, his mentor, a surrogate father. I knew Chapo trusted Vicente more than his own kids. If Vicente hadn’t been so careless, the Mexicans would never have arrested him. He was driving a nice car and going to nightclubs. Even though the Mexican cops were all being bribed, Zambada was so cocky and flashy with his money they thought they had to make a move.

But sitting there in the safe house in Illinois, his arrogance and cluelessness really shocked the s--- out of me. It was one of those moments when you sit back and think: Now, I get it. I understand the way these people think. Criminals are animals. They’re ruining their own country and they’re ruining ours, and they tell each other, tell themselves, they’re in a war. As if they had no choice.

Maybe Zambada never pulled the trigger himself. He may never have dirtied his hands like that. But that didn’t matter to me. It was the orders he gave.

His father brought him up in the business, and he knew exactly what he was doing. To hell with this guy, I thought. I’ve had enough. I wasn’t going to dignify him with my presence any longer. I got up from my chair, turned around and left.

I was pissed off and disappointed, too: Is this what I worked my whole career for, to sit down and look into the face of this turd? Lorino asked me on the way out what I was thinking. I didn’t know what to say. I just shrugged my shoulders.

“Let’s just get outta here. There’s nothing here.”