Emraan Mohamad Yakuv remembers being hit with the frigid cold when he arrived from tropical Malaysia nearly eight years ago.

As a child, he had been among thousands of refugees who fled Myanmar (formerly known as Burma). Many went to Thailand, then Malaysia. Some, years later, settled in the United States.

Yakuv, who is Rohingya, recalled being afraid of this new place called Chicago but also excited at the possibilities and happy the persecution he and his family had faced was soon a thing of the past.

Last week, Yakuv was at the Rohingya Cultural Center in West Ridge for a jobs fair, where he was helping out as a translator. A smile peeking around his face mask, he said he was doing it to help other refugees overcome the same hurdles he faced all those years ago.

Since 2011, a growing number of Rohingya refugees have settled in West Ridge, one reason the neighborhood’s Asian population has steadily increased over the past 10 years.

Those refugees aren’t drawn by proximity to work and certainly not by the winter temperatures. Rather, many say, it’s the neighborhood’s diverse culture, along with easy access to social services.

“This neighborhood is such a beautiful place because we have every color, and we see each other and respect each other,” Yakuv said. “Everyone is nice no matter if you are Jewish, Muslim, Christian and other religion, or if you’re Latino, Black or white. West Ridge is beautiful and safe. Why wouldn’t we want to live here?”

The Rohingya people are a Muslim ethnic minority who for centuries lived in Buddhist Myanmar but have not been recognized as citizens since 1982. According to USA for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, a Washington-based nonprofit, the Rohingya people are the largest stateless population in the world. That status means many Rohingya families have been denied basic human rights.

Exclusionary citizenship laws in Myanmar and renewed violence by the state within the past 10 years have forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to seek refuge in nearby Bangladesh, Thailand and Malaysia.

And far away, such as in West Ridge, where more than 2,000 Rohingya have settled. It is believed to be the largest Rohingya population in the United States.

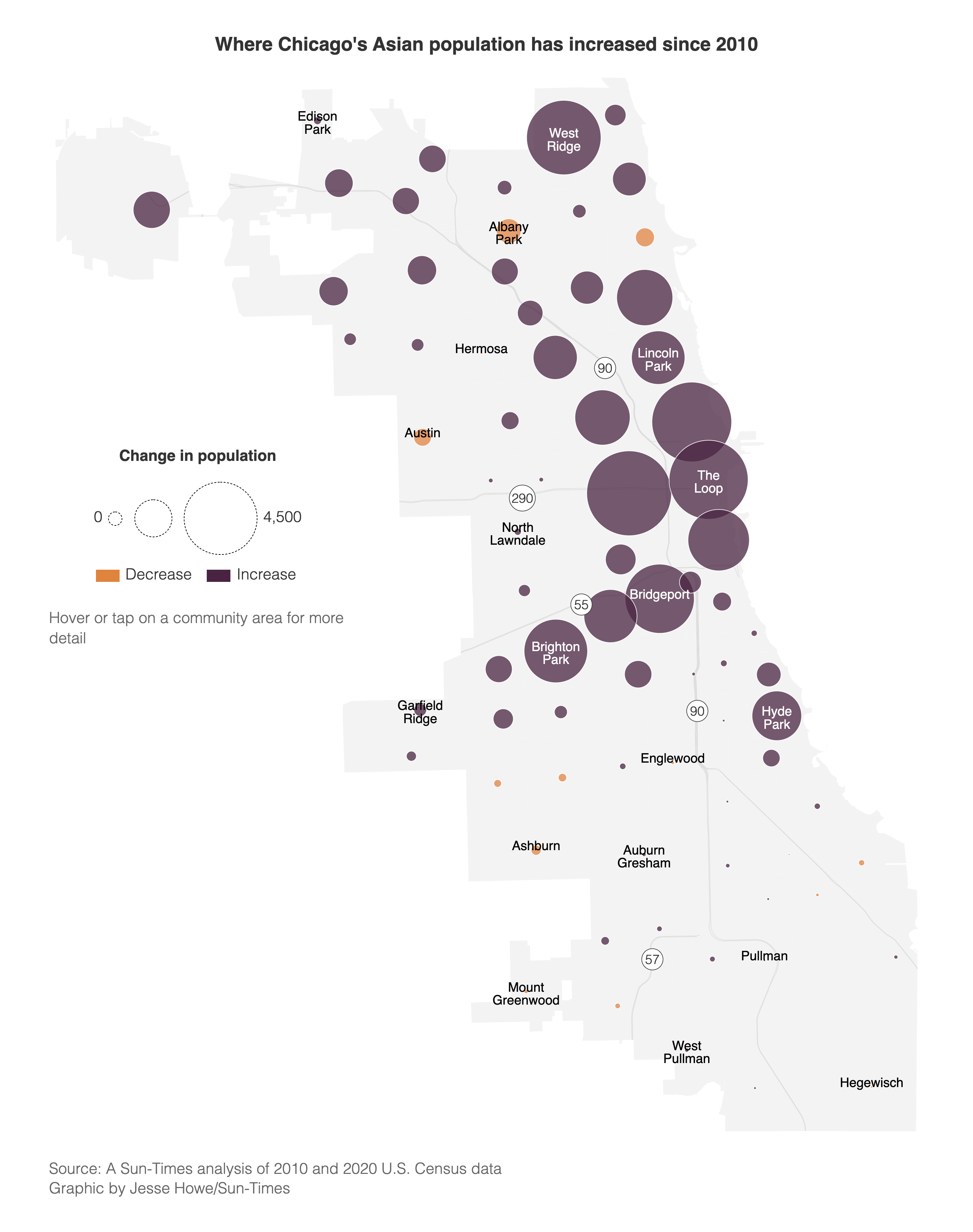

West Ridge, already one of the most diverse communities in Chicago, saw its Asian population grow by more than 22% over the past decade, according to a Sun-Times analysis of U.S. Census data. The Asian population grew from 16,184 in 2010 to 19,815 in the most recent count.

Overall, about 77,000 people call West Ridge home. Whites are the biggest racial group, with 28,212 residents, though that is nearly 2,500 less than the white population listed in 2010 (30,706). Asians are the second-largest group, while the 15,307 Latino residents are the third-largest racial group in the area.

Yakuv said when he arrived in Chicago in 2014, there were only 10 other Rohingya families.

Nasir Zakaria is director of the Rohingya Cultural Center, 2740 W. Devon Ave., which opened in 2016. He estimates they now serve about 300 families and are the most robust Rohingya social service group in the country.

“We noticed every community had some type of organization, and with us being a new cultural group in Chicago, we didn’t have a space,” Zakaria said. “We weren’t allowed to have an education in our country, so many people don’t know how to read. So we provide classes to help them learn English and [also provide] other kinds of assistance.”

Zakaria said word of mouth among Rohingya refugees has made Chicago a preferred destination for many. Families tell each other the city’s beautiful and, more importantly, that Rohingya have fostered a vibrant community on the North Side.

Another member of that community is Basha Ahmed, who arrived in Chicago from Malaysia in 2012 when he was just 12 and has lived in the same West Ridge apartment since then.

“We didn’t have internet, we didn’t have anything to learn about ourselves. But the Chicago Public Library was so close that I spent every bit of time I had there,” Ahmed said. “It helped me learn about computers and learn things that I could take back to my family.”

“That’s one big reason why I love this community,” he said.

Now 22, Ahmed spends most of his time setting up computers for residents and making sure everyone has internet access. He’s earned an associate’s degree and has several certifications to work in IT, which he hopes to do after he finishes school.

“If you look at our history, many of our older people aren’t educated and never had a chance to learn about technology,” Ahmed said. “That is my role, to help out and give back with helping educate people.”

Jims Porter, communication and advocacy manager for RefugeeOne, said another factor making West Ridge a destination for Asian immigrants is affordability.

“If you look at the past 15 years, the trend of immigrants settling in Chicago tended to be in Buena Park and the Uptown area. But rising rent has made it more difficult to live there [while] in West Ridge it is more affordable, and it offers so many social services.”

RefugeeOne, which helps provide housing and job assistance to refugees, was located in Uptown for over three decades but moved to West Ridge after they were forced out by developers.

Uptown’s Asian population dropped nearly 4% from 6,414 in 2010 to 6,182 in 2020, according to the Sun-Times analysis.

Porter believes West Ridge’s Asian population will only continue to grow. Now, he said, recent Afghanistan refugees have started settling in the neighborhood.

“West Ridge is a really culturally diverse and rich neighborhood that is home to many immigrant and refugee families,” Porter said. “And it probably will be for a long time to come.”

Jesse Howe contributed to this report.