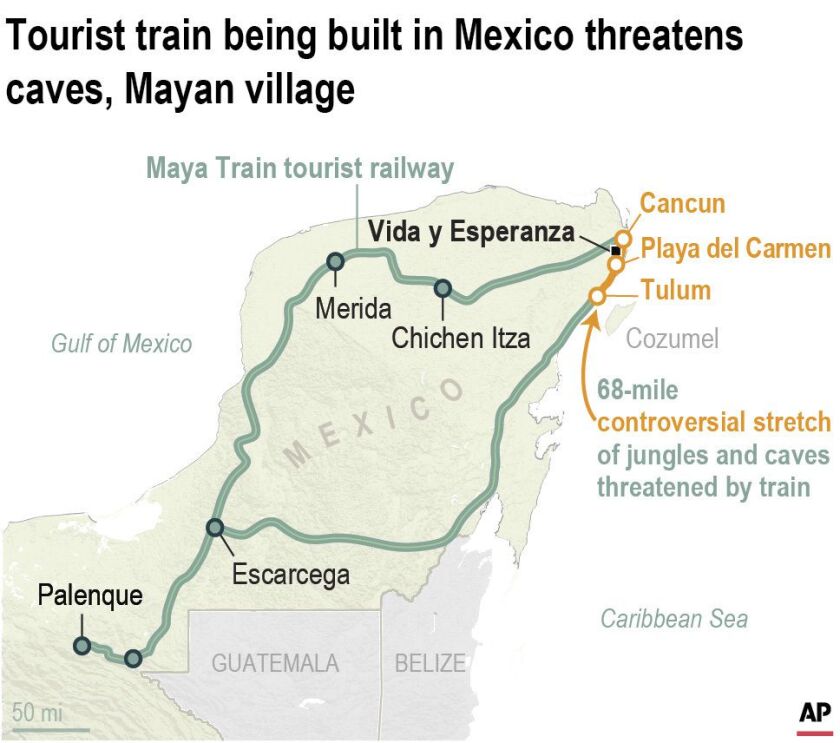

One stretch cuts a swath of more than 68 miles through the jungle between the resorts of Cancun and Tulum over some of the most fragile underground cave systems in the world.

A signature project of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the Maya Train has drawn objections from environmentalists, archaeologists and cave divers, who have held protests to block backhoes from tearing down trees and scraping clean the thin layer of soil.

It means even more to the largely Maya inhabitants of the village of Vida y Esperanza — a clutch of about 300 people whose village name means “Life and Hope.” The train is going to run right by their doors. And, as it does, they fear it will pollute the caves that supply their water, endanger their children and cut off their access to the outside world.

Lidia Caamal Puc sits on a dirt road in her community of Vida y Esperanza, where forest was cleared for the Maya Train route in Quintana Roo state, Mexico. “I think that there is nothing Maya” about the train, Puc said. “Some people say it will bring great benefits, but, for us Mayas that work the land, that live here, we don’t see any benefits. Rather, it will hurt us because, how should I put it, they are taking away what we love so much, the land.”

Eduardo Verdugo / AP

A few miles away from the acres of felled trees where the train is supposed to run, archaeologist and cave diver Octavio Del Rio points to the Guardianes cave that lies directly beneath the train’s path. The cave’s limestone roof is only two or three feet thick in some places and almost certainly would collapse under the weight of a speeding train.

“We are running the risk that all this will be buried and this history lost,” Del Rio says.

Raul Padilla, member of the Jaguar Wildlife Center which works to protect jaguars, inside a miles-long cave system known as “Garra de Jaguar,” or The Paw of the Jaguar,” underneath the planned route of the Maya Train in Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo state, Mexico. Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador wants to finish the entire train in 16 months by filling the caves with cement or sinking concrete columns through the caverns — the only places that allowed people to survive in this area.

Eduardo Verdugo / AP

López Obrador dismisses critics like Del Rio as “pseudo-environmentalists” funded by foreign governments.

As with his other signature projects, including a new airport in the capital and a massive new oil refinery on the gulf, the president exempted the train from environmental impact studies. He also invoked national security powers to forge ahead, overriding court injunctions.

Critics say López Obrador’s obsession with the projects threatens Mexico’s democratic institutions. But the president says he wants only to develop the historically poor southern part of Mexico.

“We want to take advantage of all the tourism that arrives in Cancun so they can take the Maya Train to see other natural beauty spots, especially the ancient Mayan cities in Yucatán, Campeche, Chiapas, Tabasco,” López Obrador has said.

A bulldozer, sittinge during repairs, that has been clearing a path through the forest to make way for the Maya Train in Akumal, Quintana Roo state, Mexico. The Maya Train is one of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s signature projects but has drawn objections from environmentalists, archaeologists and cave divers.

Eduardo Verdugo / AP

The Maya themselves are scraping a living from the limestone bed of the dry tropical jungle. The ancient civilization reached its height from 300 A.D. to 900 A.D. on the Yucatan Peninsula and in adjacent to parts of Central America and is best known for building monumental temple sites like Chichen Itza.

The Mayas’ descendants continue to live on the peninsula, many speaking the Mayan language and wearing traditional clothing while conserving traditional foods, crops, religion and medicine practice, despite the conquest of the region by the Spanish between 1527 and 1546.

“I think that there is nothing Maya” about the train, says Lidia Caamal Puc, whose family came from the town of Peto in the neighboring Yucatan state to settle here 22 years ago. “Some people say it will bring great benefits. But, for us Mayas that work the land, that live here, we don’t see any benefits.

“Rather, it will hurt us because, how should I put it, they are taking away what we love so much, the land.”

When marines showed up a month ago to start cutting down trees in preparation for the train on the edge of the village, people who hadn’t been paid for their expropriated land stopped them from working.

The head of the village council and a supporter of the train, Jorge Sánchez, acknowledged that the government “had not paid the people who were affected” even though the government has said they will get compensation.

But it’s not just about the money, according to Sánchez, who says, “It will bring back jobs for our people.”

The 950-mile Maya Train line will run roughly in a loop around the Yucatan Peninsula, connecting beach resorts and archaeological sites. But in Vida y Esperanza, the train will cut directly through the narrow, rutted four-mile dirt road that leads to the nearest paved highway.

But those estimates are widely doubted because López Obrador is betting on luring beachgoers to the ruins and Indigenous towns for “cultural tourism.” even though it isn’t clear how many want to combine those activities, especially if the high-speed train zooms past the beauties of the low jungle.

Unless the army, which is building the train line, constructs a large overpass bridge above the tracks, villagers would be forced to take a back road four times as long to get to the highway. It no longer would make economic sense to live there.

The government tourism agency that oversees the train project, Fonatur, says an overpass will be built for Vida y Esperanza. But such promises have gone unfulfilled in the past.

And the army plans to fill the underground caves to support the weight of the passing trains, which could block or contaminate the underground water system.

The high-speed train can’t have at-grade crossings and won’t be fenced. Which means that trains goingt 100 miles an hour trains will rush past an elementary school to which most of the students walk.

Luis López, 36, who works at a store and opposes the train, says “it might bring minor benefits, but it has downsides.

“The cenotes will be filled or contaminated,” he says, referring to the sinkholes that villagers rely on. “I survive on the water from a cenote to wash dishes, to bathe.”

Many who live in Vida y Esperanza must rely on diesel generators and would much rather have electricity than a tourist train that will rush by and never stop there.

Mario Basto, 78, who works as a gardener, says he’d rather have decent medical care than the train.

“It seems like the government has money it just needs to get rid of, when there are hundreds of hospitals that don’t have medicine,” Basto says.

Some in Vida y Esperanza support the train project because of jobs it has brought during construction.

Benjamin Chim, a taxi and truck driver who is employed by the Maya Train, will lose part of his land to the project. But he says he doesn’t care because “it is going to be a benefit in terms of jobs.”

The Maya Train also would threaten something older than even the Mayas. Del Rio discovered human remains of the Maya’s ancestors that might date as far back as 13,700 years in another cave network — but it took him and other divers a year and a half to snake through a single cavern system. “This is work that takes years, years,” he says.

López Obrador wants to finish the entire train in 16 months by filling the caves with cement or sinking concrete columns through the caverns — the places that allowed people to survive in this area.

For the villagers, much of the damage already has been done.

“They have already stolen our tranquility the moment they cut through to lay the train line,” Caamal Puc days.