A long-secret investigation of a whistleblower’s complaint has found widespread and longstanding problems with the federal government’s administration of the GI Bill that could be at fault for veterans and their families having been denied money they were entitled to for college.

The investigation found that, because of bad record-keeping, some vets were shortchanged on their service time — a key element in qualifying to transfer their Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits to their children to pay for school.

In a series of reports since 2019, the Chicago Sun-Times has documented how such bureaucratic errors led to the children of long-serving veterans losing out on Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits for college. In some cases, families were told they had to repay college money the government already paid on their behalf.

The Defense Department investigation into whistleblower Nicholas D. Griffo’s complaint was completed in January 2020. But the federal agency never released its findings. Griffo provided the report to the Sun-Times, saying he was frustrated that the government hadn’t made it public after 22 months.

Among the report’s findings:

- “Known gaps” exist in service data for reservists from all branches as well as National Guard members because the various military branches failed to properly log some active-duty periods in their records.

- The errors have meant those veterans were shorted on their qualifying service time toward valuable Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits they’re entitled to.

The federal Department of Veterans Affairs relies on service records to determine whether a veteran qualifies for benefits including the college entitlement. So it’s likely that vets wrongly have been denied benefits they’d earned, the investigation found.

The report doesn’t say how many veterans might have wrongly lost out.

Griffo says “hundreds of thousands” of vets could be affected.

“These gaps have been known since September 2009 and the Department of Defense has been working on a continuous basis to close those gaps so active-service data history is complete and accurate,” William H. Booth, the Defense Department’s human resources director, wrote to the U.S. Office of Special Counsel on Jan. 24, 2020, in a letter accompanying the never-released investigative report.

The Defense Human Resources Activity Headquarters conducted the investigation at the request of the Office of Special Counsel.

The Sun-Times has reported on numerous veterans who were told they could count on Post-9/11 GI Bill money for their kids’ college only to discover years later they couldn’t transfer those benefits to dependents.

Most had agreed to stay on longer in the military — typically for four extra years — to qualify to transfer their GI Bill benefit, which covers up to four years of tuition, housing and books.

In some cases, their children already had been getting money for tuition and other expenses, only to be told later that the veteran-parent’s service record was lacking — and the government was now demanding they pay back the money they’d paid toward tuition and other college expenses.

Two former DePaul University students were among those who had their college money canceled — and got debt-collection notices from the government demanding they repay $20,000 to $70,000.

Griffo, a veterans claims examiner since 2008 at the VA’s regional office in Buffalo, New York, says that, for years, certain types of active duty in the reserves — for training, operational support and “special work” — wasn’t counted as it should as qualifying time toward Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits.

Vets often don’t realize there are problems with the records of their service time, which can be complicated, especially when they include active-duty military and the reserves.

“They didn’t know they’re being screwed,” Griffo says. “They trusted the VA.”

He says the mistakes were compounded by VA employees and benefits contractors not recognizing the errors — and by a culture he says put handling claims quickly above all else.

Vets seeking information “can get five different answers from two different people at the call center,” Griffo says. “They want you to feel good and get the hell off the phone.”

Defense officials said in the report the military is transitioning to an online portal that lets service members keep better tabs on their records, which they said should cut down on errors.

Asked about the long-withheld whistleblower investigation, the Department of Defense and the VA both said they’re looking into it.

Griffo, 51, has 20 years of qualifying service with the Navy and Navy Reserves, including two years on active duty in the 1990s. He says that his service and his work as a Navy career counselor — as well as his fight to overturn his own denied GI Bill claim — gave him unusual insight into the problems at the Defense Department and the VA.

He says he flagged the issues for his VA bosses as early as 2008 but grew frustrated as time dragged on and problems continued.

Griffo occasionally has butted heads with his bosses over mistakes he saw that hurt veterans. Though his performance review in October 2020 had only “exceptional” or “fully successful” marks and praised his “high proficiency in his quality of work,” the VA has notified him it’s planning to fire him over what it describes as improperly processing claims. Griffo denies doing anything wrong and says the move is in retaliation for his complaints.

Though his complaint narrowly focused on record-keeping problems for reservists, some vets say Griffo’s portrayal of an opaque, at times dysfunctional bureaucracy fits their experiences.

“It seems like there’s just a total disorganization,” says Rebecca Dougherty, whose father served 20 years on active duty and in the reserves with the Marines.

Years after the VA authorized paying for her to attend Boston University on her dad’s Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits, Dougherty got a debt notice from the government, saying he didn’t qualify after all and demanding she repay $87,000. Her younger sister got a similar demand for $27,000 for her education at the University of South Carolina.

Dougherty’s father, saying he did qualify, tried to correct what he says were errors on his service record by going to a Navy board that hears such cases. Dougherty says the problem still hasn’t been fully resolved.

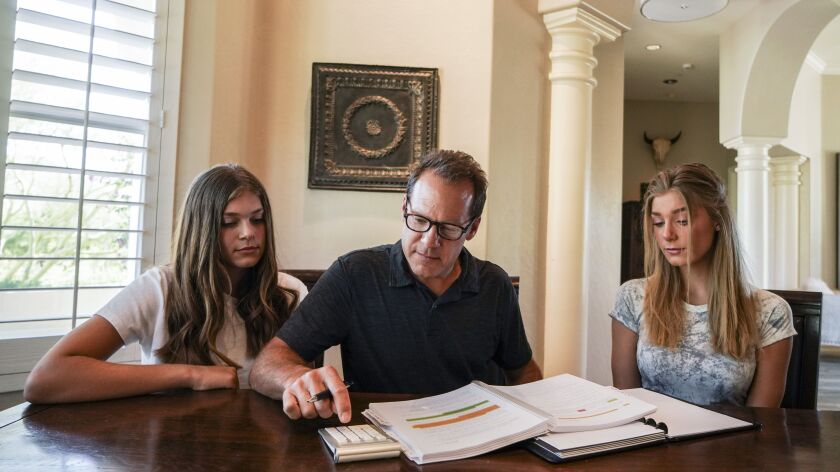

John Capizzi, a retired Navy commander with 20 years on active duty, fought a similar battle after finding out his planned transfer of Post-9/11 GI Bill money to his daughters was denied because the VA said he retired six months too early.

The Scottsdale, Arizona, veteran eventually prevailed but says he’s troubled by the hassles other families are still facing.

The Navy knows there are problems with the records and what vets were told, Capizzi says. “It’s just that nobody wants to fall on the sword,” he says. “Nobody wants it to be on their watch.”

Tim McHugh, a Virginia lawyer and former Army paratrooper, says he has seen numerous cases in which clerical errors derailed people’s ability to tap GI Bill benefits.

“The veteran is left totally at a loss of how to fix it,” McHugh says. “These are folks who trusted the government and trusted the military to do right by them.”