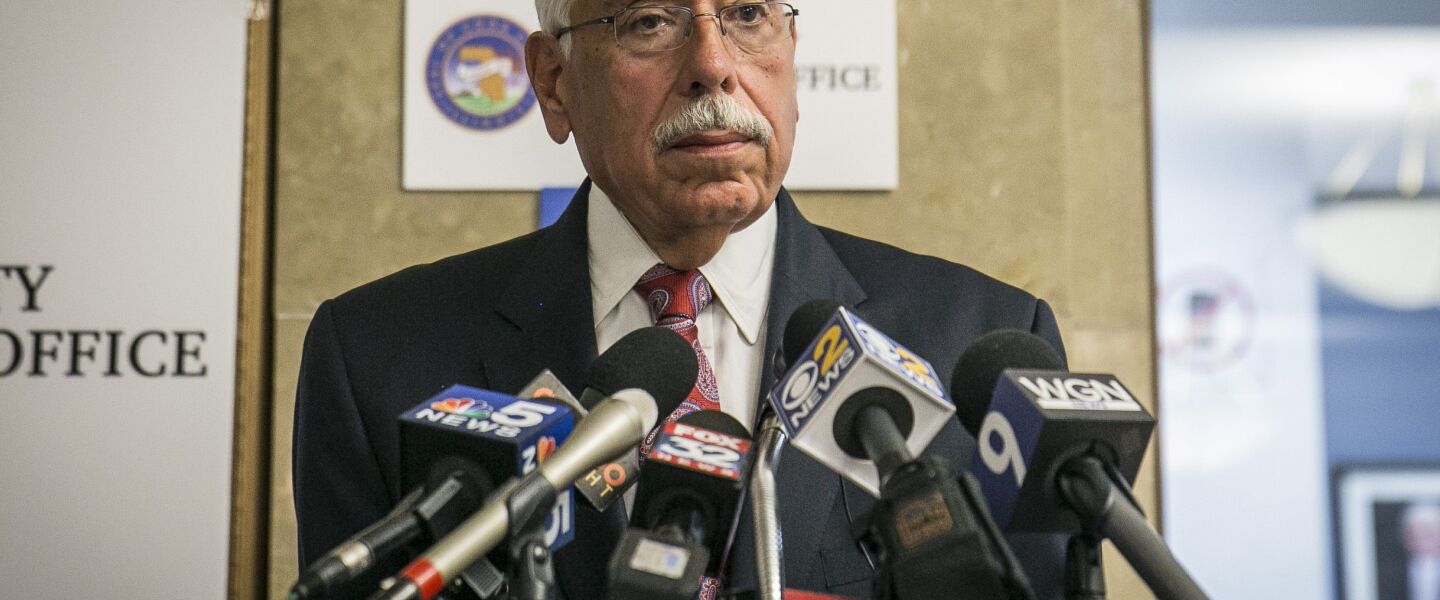

And even after the listed homeowner, Joseph J. Lombardi, died, Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi and his predecessor Joseph Berrios kept granting those tax breaks in his name, records show.

For six years.

Someone kept filling out paperwork in the name of the dead man, who’d been paroled to that address after serving time in prison on a conviction for threatening to kill a man who owed “juice” loans to Lombardi and other mobsters.

Kaegi’s investigators confirmed in December 2020 that Lombardi had died years earlier. That was after they visited the home, which remains in his name.

The assessor’s staff determined that whoever really does own the home would have to repay the tax breaks they got that they weren’t entitled to — altogether $22,884 in taxes, penalties and interest.

They say they’ve sent two bills since then, though their records show just one, dated Oct. 20, about 10 months later. That was one week after Chicago Sun-Times reporters asked the assessor’s office to see files for Lombardi and eight other homeowners who’d been granted tax exemptions they weren’t entitled to. In one case, the breaks came to more than $160,000.

Lombardi and six of the other homeowners got “senior citizen assessment freezes” from the assessor, drastically reducing their taxes, even though they didn’t qualify for the break, which is limited to people 65 and older with a household income of less than $65,000.

One of those receiving the senior assessment freeze also was among three Cook County homeowners who got disabled veteran tax breaks from the assessor — an exemption that could erase their entire property tax bill for life — even though they had never even applied for the break because they hadn’t served in the military.

Four of the nine homeowners getting the exemptions they weren’t qualified for discovered the mistakes themselves. Fearful they could be charged penalties for receiving tax breaks they weren’t entitled to, they reported the errors to the assessor and paid what they owed.

The owner of a Berwyn two-flat got the assessor to remove the disabled veteran exemption that reduced his tax bill last year to zero — but then the assessor made the same mistake again this year. The second error was cleared up last month.

The assessor calls mistakes like these “erroneous exemptions” and has 10 people whose job is to get back the money that homeowners received, whether they applied for a break they didn’t qualify for or the assessor just mistakenly gave it to them. The unit is funded by the penalties and interest paid on the tax mistakes its investigators uncover.

Since 2015, 13,349 homeowners have been found to have gotten tax breaks they shouldn’t have received from the assessor’s office — and have been asked to repay $48.4 million in property taxes, penalties and interest, according to a Sun-Times analysis of records from the assessor and the Cook County treasurer’s office.

Two-thirds of that money has been repaid by homeowners making full or partial payments, but 2,170 others have paid nothing, the analysis found.

Kaegi’s spokesman Scott Smith points to the hundreds of thousands of people applying for property tax breaks every year and says it’s “not possible to review every application each year” to verify that homeowners qualify.

“The assessor acts to eliminate instances of erroneous exemptions,” Smith says. “Because of these efforts, erroneously received exemptions have not had a significant impact on the tax bills of the people of Cook County.”

Since Kaegi took office three years ago, Smith says, his staff has recovered $15 million from the owners of more than 9,800 homes who got tax breaks the assessor shouldn’t have granted.

Under Illinois law, homeowners who got bogus exemptions must be notified and offered a hearing. For those who don’t repay what they’re found to owe, the assessor can place a lien on the building so the county can recover the money that’s owed, including penalties and interest, when the property is sold.

But Kaegi’s office doesn’t always file liens against homes whose owners owe taxes, records show.

Sun-Times reporters filed a public records request Oct. 13 with Kaegi’s office for files involving nine properties with multiple erroneous exemptions, including Lombardi’s. Kaegi’s staff didn’t release the records, as required under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act, until Dec. 3, after the Sun-Times appealed to Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul to order them to do so.

The files show Lombardi got two tax breaks earmarked for people over 65 — a senior citizen exemption that typically reduces property taxes by hundreds of dollars a year and the far more lucrative senior assessment freeze, which can save those who qualify thousands of dollars.

Lombardi started getting the tax breaks in the early 2000s, after getting out of federal prison, where he served nearly three years after being convicted of threatening to kill someone who owed money in a loan-sharking case.

The assessor’s office should have halted the tax breaks after Lombardi’s death on Nov. 15, 2013.

But someone kept applying for those tax breaks, submitting applications each year, saying Lombardi still had a household income of about $12,000 and signing his name, according to copies submitted to the assessor’s office for 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019.

And each year, the assessor’s office — first under Berrios, then Kaegi — approved those tax breaks, which saved the homeowner $3,831 last year, resulting in a bill of $1,489.

Something changed last December, when the assessor’s office sent an investigator to Lombardi’s Bridgeview home. Kaegi’s office says it doesn’t know what prompted the inquiry.

“No one was at the residence and there was a ‘for sale’ sign on the front lawn,” Kaegi’s investigator wrote in a Dec. 18, 2020, report. “I spoke to a neighbor . . . He stated Joseph J. Lombardi had died at least five years ago and that Lombardi’s son and daughter Rosemarie and Joseph Jr. are currently living at the house. Rosemarie and Joseph Jr. Lombardi are not eligible for the senior or senior freeze exemptions.”

Kaegi’s staff determined that the assessor’s office had given erroneous exemptions to the homeowner for 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019, totaling $22,884 in taxes, penalties and interest that must be repaid.

Smith says the assessor sent a bill last March. Another notice went out Oct. 20, a week after reporters asked about the home.

But no payments have been made. Rosemarie Lombardi has asked for a hearing on the matter, which will be held Jan. 27.

“We are still determining who applied for those exemptions, which will be explored during the hearing,” Smith says.

The assessor has revoked all of the exemptions for the home, which now has a tax bill of $6,670.

Rosemarie Lombardi says she doesn’t know who filed the applications and blamed county officials for the screw-up.

She initially told a Sun-Times reporter her father died in January 2018, not November 2013 — which could have meant he was eligible for most of the tax breaks. She later confirmed her father died in 2013 at Elmhurst Hospital.

“Frankly, I didn’t know who you were,” she told a reporter. “So you have to forgive me if I gave you different dates. I don’t give out personal information.”

Lombardi was among seven reputed mobsters — including Michael “Big Mike” Sarno, who’s been identified by authorities as Cicero’s onetime mob boss — convicted after being indicted in 1993 in a loan-sharking case in which prosecutors said they were trying to force a debtor to pay 260% interest on a series of small loans.

“See, with the electric company, you don’t pay your bill, they shut your f—ing electricity off,” Lombardi told the victim, according to prosecutors. “With me, I’ll cut your f—ing breath off. So now you decide which is more dangerous: Would you like to live without electric, you like to live without gas, or if you like to live.”

Officials in Kaegi’s office say they don’t know whether the agency has ever asked law enforcement to investigate any homeowner for applying for tax breaks they aren’t entitled to.

Others who received erroneous exemptions include:

- Allen Cosnow, who ended up facing one of the largest erroneous exemption bills for a single property, owing $112,907 in taxes and interest on his Glencoe home.

Kaegi’s office notified him he’d have to pay that amount after Sun-Times reporters asked about how the retired veterinarian qualified for an income-tied senior freeze on the five-bedroom home on a half-acre lot.

Cosnow, 83, was found to have been ineligible for the exemption for four years, 2016 through 2019, having “understated his income on the application,” according to Smith.

Cosnow agreed to pay the money by the end of this year to avoid having a lien put on his home. So far, he has paid $56,305 for the 2017 to 2019 tax years.

Though Cosnow was ordered to repay the senior freeze breaks for 2016 to 2019, Kaegi renewed his tax break for the past year, when the senior freeze reduced his property taxed by $22,893, leaving him with a $17,722 bill.

“I’ve had to pay an additional amount, which I’ve done,” Cosnow says.

- Marc A. Taylor, who, when he died in February 2020, owed $160,666 because the assessor said he took property tax exemptions on a Rogers Park home and two small apartment buildings in Lincoln Park between 2010 and 2016.

Somehow, the assessor’s office gave Taylor homeowner exemptions on all three properties, and he got senior citizen and senior assessment freeze breaks on two of them. Under Illinois law, a person is entitled to those exemptions only on a primary residence.

The assessor’s office “investigated these matters after receiving an external complaint” and determined he didn’t live in any of those buildings, Smith says.

Three years ago, days after Kaegi took office, the assessor’s staff had placed liens on those properties — a home in the 1400 block of West Jarvis Avenue, an apartment building in the 1800 block of North Bissell Street and another in the 300 block of West Armitage Avenue — to collect the taxes when the properties are sold.

Taylor never made any payments on the debts before he died at an Evanston hospital. The three buildings — and the debts — are now part of his estate, managed by his brother Patrick Taylor.

“If the estate owes it, we’ll pay it when the property is sold,” Taylor’s attorney Rebecca Little says.

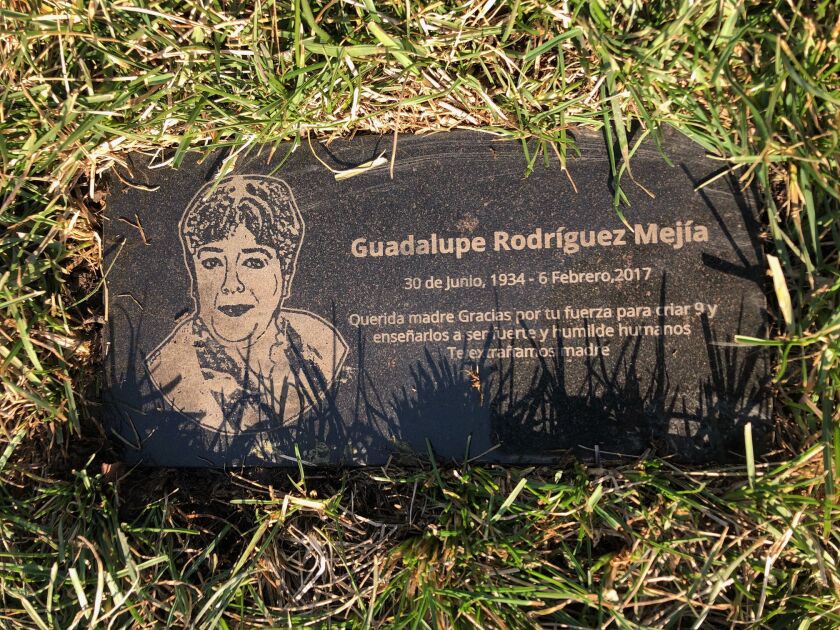

- The owner of an apartment building in Pilsen, where a dispute among siblings led the assessor’s office to discover it had, for two years, erroneously granted a senior assessment freeze, a homeowner exemption and a senior exemption to Guadalupe Rodriguez — after she died.

The assessor’s records show the siblings didn’t even agree that their mother was dead.

Kaegi’s office says this case started as a “squeal appeal,” in which someone in the family provided the assessor with a death certificate showing Rodriguez died Feb. 6, 2017. That’s the same date given in her death notice.

But county records show her daughter Silvia Rodriguez Mejia kept getting tax breaks in the mother’s name on the building at 2013 S. Allport St.

In April, Silvia Rodriguez Mejia told the Cook County assessor’s office that her mother Guadalupe Rodriguez was alive and offered to bring her in to prove that and that she should continue to receive the senior citizen tax breaks, records show. Rodriguez’s gravestone at Resurrection Catholic Cemetery and Mausoleums in Justice says she died in February 2017.

Lauren FitzPatrick / Sun-Times

In April, Mejia wrote the agency that her mother was alive and offered to bring her in to prove that and that she should continue to receive the tax breaks, records show.

“I think this has to do with my sister-in-law Rosa calling, saying my mother is dead,” Mejia wrote to the assessor earlier this year. “I can bring my mother or do a Zoom call.”

Mejia is being sued by her brother Aldo Rodriguez, who says he gave his sister ownership of the building and of two others while he was battling addictions, and now he wants her to give them back.

At first, Kaegi’s staff planned to place a lien against the Allport property in hopes of collecting more than $27,345 in erroneous exemptions granted to the property in 2018 and 2019 after Guadalupe Rodriguez died. But the office dropped the 2018 tax dispute and settled the case for $7,669.

“With multiple family members disputing the date of death and providing conflicting death records, the office and the judge agreed to accept one year of back payment instead of two,” Smith says.

Kaegi’s office has now removed all of the property tax exemptions from the Allport property. That made the tax bill soar from just $71 a year ago to $8,132 this year.

Mejia’s lawyer Jorge Montes says that, despite the letter signed in her name, she never disputed her mother’s death and that she has paid the full amount she was asked to pay.

- Four homeowners who were given lucrative exemptions they say they never applied for and who reported the mistakes themselves. All four have repaid the tax breaks the assessor mistakenly gave them.

“There is no record as to how these exemptions were erroneously received,” Smith says, “but it does not appear to be due to the taxpayer applying for the exemptions.”

Berwyn homeowner Jerry Cardaropoli had just straightened out an erroneous disabled veteran’s exemption, repaying the $7,370 break he’d been given last year by mistake on his two-flat, when he got his tax bill this past summer — which repeated the same error, this time for $8,483.

Cardaropoli says the mistakes jumped out at him because both bills showed he owed zero taxes.

“They made me out like a veteran, and I’ve been trying to straighten that out,” says Cardaropoli, who says he was never in the military and never claimed to be. “It’s a battle to get it right. And, if I ignore it and don’t pay the taxes, they’ll come after me, and it’ll be my fault.

“They just messed up. It’s been going on for two years.”

Asked why Cardaropoli was given the erroneous exemption again after he had straightened things out, Smith says, “Processing of exemption applications is handled by a different department from the erroneous exemptions department.”

Charles Tokar, the mayor of Chicago Ridge since 2013, also received a disabled veteran’s exemption in 2017 that wiped out one of the two tax bills he gets on his home. Like Cardaropoli, he isn’t a veteran and says he never pretended to be, so he reported the mistake.

“I didn’t do it,” Tokar says. “They might have screwed it up somehow. I doubt that my tax guy would have put that down.”

He quickly repaid the erroneous $5,634 break.

Steve Gutmann was shocked when he got his property tax bill in the summer of 2020. He normally paid more than $8,000 in taxes on his Glenview home, but this bill said he owed nothing.

“They gave me an exemption for a disabled veteran,” Gutmann says. “I was never in the military, and I’m not disabled.”

He called Kaegi’s office, got the bill corrected and paid on time last year.

“They said somebody key-punched something” that made it appear he qualified for the disabled vet tax break, Gutmann says.

It wasn’t the first time Gutmann got an exemption he shouldn’t have. Records show that, in 2015, Berrios gave Gutmann a senior assessment freeze he didn’t apply for or qualify for, which cut his tax bill by $1,640.

Stephen Novack, an attorney, also discovered Berrios gave him a tax break without asking.

Novack represented the former Park Grill when then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration unsuccessfully sued to break the sweetheart deal that Mayor Richard M. Daley had given the Millennium Park restaurant.

Novack paid the $21,518 tax bill he was sent in 2017, saying he didn’t realize it included a senior citizen assessment freeze that cut the bill by $3,393.

Novack says he never applied for the tax break — he wouldn’t have been eligible because his annual income tops $65,000.

“It was a complete surprise to me,” he says. “I called and told them they gave me a break I didn’t deserve. I gave back what they mistakenly gave to me.”

He wrote a check to pay the county what he owed on Jan. 9, 2019, shortly after Kaegi took office.

- The owner of a Southwest Side home that the assessor’s office said owed $33,944 for 27 erroneous tax breaks over seven years.

Darlene Curry says she found out about the erroneous exemptions a month after her 91-year-old mother died in December 2018.

The assessor’s office sent Curry a bill for exemptions her mother Irene Banuch received between 2011 and 2017, years after Banuch transferred title of the home where she lived to her daughter.

Darlene Curry, who lived elsewhere, says her mother continued to live in this Southwest Side home and to pay the utilities and property taxes and that she thought her mother had added her to the deed as a co-owner, which would have entitled Irene Banuch to keep getting the exemptions for homeowners and senior citizens.

Anthony Vazquez / Sun-Times

Curry, who lived in the suburbs, says her mother continued to live in the home and to pay the utilities and property taxes. She says she thought her mother had added her to the deed as a co-owner, which would have entitled Banuch to keep getting the exemptions for homeowners and senior citizens while Curry claimed exemptions on her own home.

“It was a horrible ordeal,” Curry says. “I was under the assumption that my mother added my name to her house. My attorney told me in order to sell the house I had to pay all these back taxes.”

She paid up in February 2019.

But the assessor prepared a new bill on Oct. 20, a week after the Sun-Times asked about Curry’s case.

Curry says she hasn’t received that notice, which is regarding taxes the treasurer’s office confirms already have been repaid.

Smith says Banuch “would have been granted an exemption” if she had a signed lease with her daughter to show she was living there and responsible for the taxes.