It is a somber ride, filled with a heavy dose of history, rich with triggers for reflection.

About 150 Chicagoans recently took the journey, starting at the lakefront at 29th Street — site of the city’s lone marker acknowledging the events that began at 29th Street Beach on July 27, 1919 — and crossing the glistening new 35th Street Bridge to stop at sites of terror 100 years ago, in neighborhoods now called Bronzeville, Bridgeport and Back of the Yards.

“Chicago 1919 Bike Tour: Visualizing the 1919 Riots in Today’s Chicago,” was part of “Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots,” a yearlong initiative the Chicago Sun-Times first wrote about in March, when we introduced you to 107-year-old Juanita Mitchell.

The south suburban woman, then 8 years old, gave a firsthand account of how women and children hid in her home as the men stood guard by the window, on that fateful day.

Beaches were packed, and black youths playing on a raft drifted over an invisible line separating whites and blacks at 29th Street Beach — angering whites.

George Stauber, a 24-year-old white man, hurled stones at the boys until 17-year-old Eugene Williams fell off the raft and drowned. Daniel Callahan, the first police officer to arrive, refused to arrest Stauber — angering blacks.

A popular destination for Southern blacks during the Great Migration and World War I, the city already was a tinderbox of racial tensions and quickly erupted into what today remains the most violent week in Chicago history. It was among a string of nationwide outbreaks of racial and labor conflicts collectively known as “Red Summer.”

At the end of those five days, 38 people were dead — 23 black, 15 white; 520 Chicagoans were injured — two-thirds of them black. White gangsters torched homes, leaving some 1,000 black residents homeless.

From the beach, the bike tour’s first stop is the city’s oldest black Baptist church, the 145-year-old Olivet Baptist at 3101 S. King Drive. With some 11,000 members during the 1920s, it was the largest black church in America and largest Protestant church in the world.

An active station on the Underground Railroad during slavery, Olivet was a de facto community center in Chicago’s segregated “Black Belt,” home to 40 different social, economic and cultural organizations, and during the riots, it was headquarters for those working to restore peace.

“Eugene Williams drowns. Police refuse to arrest the white guy. African Americans on the beach are furious. At some point, an African American man shoots a gun at police. Someone gets injured. Police chase him over the tracks, towards Olivet, and about two blocks northeast, they shoot and kill the guy,” said D. Bradford Hunt, vice president for research and academic programs at The Newberry Library, who helped lead the tour.

The man was James Crawford, 37, a Southerner who’d come up from Georgia, shot at 6 p.m. on July 27 at 29th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue.

Details about those who died that week, both black and white, can be found in an interactive map created by University of Chicago sociologist John Clegg. It also lists the injured and incidents of arson and bombings, with photos and newspaper articles.

Users can zoom in on where people were murdered and see their occupations and even the exact cause of death. It’s a chilling accessory to the bike tour.

“I created it by combing through archives for any info we could locate spatially, with addresses or sometimes just a street corner . . . data points that we could map for people interested in this mostly forgotten history,” Clegg said. “We realized we mostly had incidents of violence.”

Clegg and a handful of assistants spent six months on the research, the final result based on primary sources from newspaper articles to the 1922 Chicago Commission on Race Relations report, “The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot.”

Led by black sociologist Charles S. Johnson, the 672-page report’s findings of systemic racism came with 59 recommendations for municipal reform — recommendations that went nowhere.

From the church, the tour takes in several Bronzeville sites:

• 3624 S. King Drive, once home of famed civil rights activist/journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, who took testimony from riot victims and appeared before a grand jury on their behalf.

• 3365 S. Indiana Ave., a home bombed with homemade explosives or Molotov cocktails, which white gangs used to destroy much of the “Black Belt.”

• 3501 S. Wabash Ave., now the Chicago Police Department headquarters parking lot. In 1919, it was the site of the Angelus, the only building in the “Black Belt” with predominantly white residents. Four people were killed there during a clash between police and blacks.

• Across the street is De La Salle Institute, where the late Mayor Richard J. Daley graduated in 1919. Daley was a member of the Hamburg Athletic Club, a Bridgeport Irish gang cited for some of the beatings and bombings but he denied taking part.

• 244 E. Pershing Road, Wendell Phillips High, where racial demographics were shifting before the riots. It became Chicago’s first predominantly black high school in 1920, producing notables such as Nat King Cole, Sam Cooke and John H. Johnson.

• 318-324 E. 43rd St., The Forum, built in 1897, was once a hub for social, political and civic events in the black community. Shuttered in the ’90s, the abandoned, 30,000-square-foot structure was reclaimed for revitalization by developer Bernard Lloyd in 2011.

Lloyd as well as Olivet Pastor John L. Smith, and Harold Lucas, president of the Black Metropolis Convention & Tourism Council, helped Hunt lead the tour, each sharing their perspectives on an infamous moment believed critical to understanding why Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in America.

In Bridgeport and Back of the Yards, the tour stops at:

• Armour Square Park, at 33rd & Wentworth streets, on the dividing line between black and white communities. Opened in 1905, it’s been the site of racial violence since 1913, including the 1997 savage beating of black teen Lenard Clark.

• The Union Stockyards Gate, at Exchange Avenue and Peoria Street, where tensions between blacks and whites over competition for its meatpacking jobs exploded during the riots.

“It’s notable that violence directed at African Americans was focused on workers during the day. They were being attacked in streetcars or on the streets as they traveled to work, particularly in the stockyards,” Clegg said.

“Injuries and deaths of African Americans occurred throughout the city, whereas injuries and deaths of whites occurred mostly in African American neighborhoods. White victims were people who had gone into those neighborhoods with a purpose of attacking. That’s something many historians hadn’t been particularly aware of.”

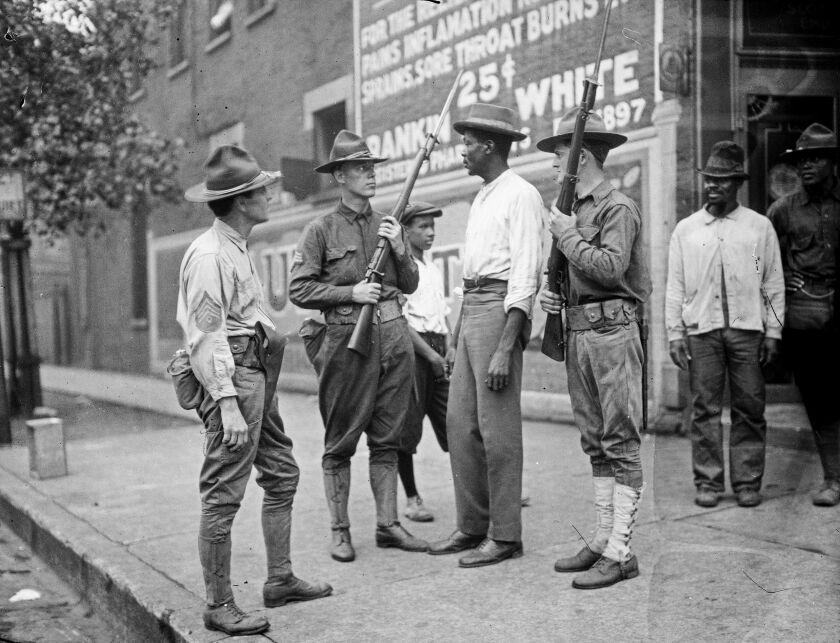

According to Newberry’s historical summary, after the confrontation on the beach, white people “loaded into automobiles and sped through black streets, firing indiscriminately at African Americans and their homes. As whites attacked, black people fought back in unprecedented numbers: a street-level expression of the growing race consciousness catching fire across the country.”

It continued: “. . . Only a handful were tried or saw any prison time — most of them black. Many of the riot’s most vicious offenders were whites protected by law enforcement and local politicians.”

107-yr-old Juanita Mitchell (w/ daughter Mary Muse) shares her memories of the 1919 Chicago race riots. #Chi1919 @DuSableMuseum pic.twitter.com/Kr5kaQZMr2

— Newberry Library (@NewberryLibrary) February 24, 2019

The bike tour, co-sponsored by Blackstone Bicycle Works in Woodlawn, is just one in the series of community conversations examining the legacy of the riots in arenas where segregation and inequality still exist.

From the historic stockyards gate, the tour circles back to culminate at 31st Street Beach.

Efforts are underway for a public art project that would erect markers at the visited sites and all other sites where people were killed and riot events occurred.

“My grandmother was about 4 when the riots happened and had very vivid memories of it,” recalled Rebecca Connie, program manager at Blackstone, which trained youth participants as marshals to guide the Chicago 1919 Bike Tour.

“I remember she told me the story of how she and her 3-year-old sister and infant brother were hiding in the basement, guarded by an uncle with a shotgun. He had been injured in the war. All the other men were out in the neighborhood standing post,” she recounts.

“Most of our kids don’t know anything about the 1919 riots. So we had to think, ‘How do you present this information in a tangible and accessible way for people?’ We know this can be traumatic, so we capped the age at 13 and went over the content with our youth marshals beforehand. It has to be: ‘How much do you know about the 1919 riots? Let’s unpack this.’ ”

The Forum in Bronzeville, near 43rd Street and Calumet Avenue, was another stop on the bike tour of important sites from the 1919 Chicago race riots. The Forum, built in 1897, has a performance hall as well as retail storefronts. Efforts are underway to restore the building.

Peter Pawinski/For the Newberry Library