James “Jim” Rudisill has jumped into dangerous situations his entire career.

During two stints in the Army that included two tours of duty in Iraq and one in Afghanistan.

And later as an FBI counter-terrorism agent, helping build cases against white supremacists and ISIS supporters.

He sees his latest mission as no less important, even if it is set in a far less threatening locale — a federal court, where he sued the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in a case his lawyers say could result in additional GI Bill benefits for potentially 1.7 million veterans seeking to further their educations.

Rudisill’s court case centers on whether the government can force veterans like himself — those who have served in the military long enough to have earned benefits under more than one GI Bill — to give up their Montgomery GI Bill benefits in order to tap the more generous benefits available to them under the Post-9/11 GI Bill.

Veterans who qualify can reap the benefits of both laws. But the federal government has imposed a cap on those benefits in a way that ends up shortchanging some vets.

That’s the argument Rudisill’s case makes — successfully so far.

In winning the civil case, his lawyers argued that the U.S. government wrongly cut short his educational benefits under the GI Bills — and that it also denies some of the nation’s longest-serving vets benefits collectively worth potentially billions of dollars to put toward college or graduate school.

For Rudisill, the difference in what he was entitled to and what he was allowed was enough that it meant having to say no to going to Yale Divinity School because of the cost.

The way the GI Bill system works can be confusing. In part, that’s because the government has enacted numerous GI Bills since the World War II era, some of them operating simultaneously. The two at the heart of Rudisill’s case are these:

• The Montgomery GI Bill, which Congress passed in 1984 to beef up the original GI Bill. It provides up to 36 months of stipends toward college tuition — effectively four years of college — for qualifying service members who have paid $1,200 into the system.

• The Post 9/11 GI Bill, which Congress enacted in 2008. It provides up to 36 months of far more generous college payments — including tuition, housing and books. And it automatically goes to those who qualify. As with the Montgomery GI Bill, with summers off, those 36 months equal enough schooling for a four-year degree.

Here’s where things can get tricky. Congress has set 48 months as the maximum combined use of GI Bill benefits. But some veterans, like Rudisill, who had used a portion of their Montgomery benefits before tapping their Post-9/11 benefits, say the government shortchanged them. It did so, they say, by forcing them to forfeit any unused Montgomery GI Bill benefits and using a formula that also limited their Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits.

You don’t have to understand the math to understand this: The bottom line for Rudisill was that he’d get only 10 months of schooling covered by the more generous Post-9/11 GI Bill rather than the 22 months he says he was entitled to.

Taking his case to the VA’s Board of Veterans’ Appeals, he argued that the VA’s stance amounted to a misinterpretation by bureaucrats of what Congress intended when it established the benefits to help veterans further their education.

That VA appeals board ruled against him. But he appealed. And last year the U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims — the Washington, D.C., court that has exclusive jurisdiction nationwide on such matters — agreed that Rudisill was right. It reversed the VA board’s ruling.

The government is now fighting that decision, taking its case to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, where arguments are set to be heard Dec. 9.

Rudisill, who is 40 and lives near Richmond, Virginia, discovered the problem in 2015 when he tried to put 22 months of his Post-9/11 benefits toward getting the graduate divinity degree from Yale, which he hoped to use to return to the Army as a chaplain in the Episcopalian tradition.

He put in for the Post-9/11 GI Bill benefits after earlier using 26 months of the allotted 36 months of tuition under the Montgomery GI Bill. By his math, with a total of 48 months allowed to any veteran, he could still get 22 months of paid schooling and housing under the better benefits provided by the Post-9/11 GI Bill. That would be enough to complete the graduate program.

Rudisill is the grandson of textile mill workers and had gone on religious mission trips as a young man to Kenya and Bolivia. He says he was “elated” to hear he’d been accepted to Yale.

“I felt like I was going to be able to give back to the service that I love so much and minister to soldiers that were still in and dealing with a lot,” he says.

He’d first enlisted in the Army in 2000 and served two and a half years before leaving the service to attend college.

As he was completing his undergraduate studies, he learned friends had been killed in action. He decided to return to military service, first with the North Carolina National Guard and then as an active-duty commissioned officer in the Army.

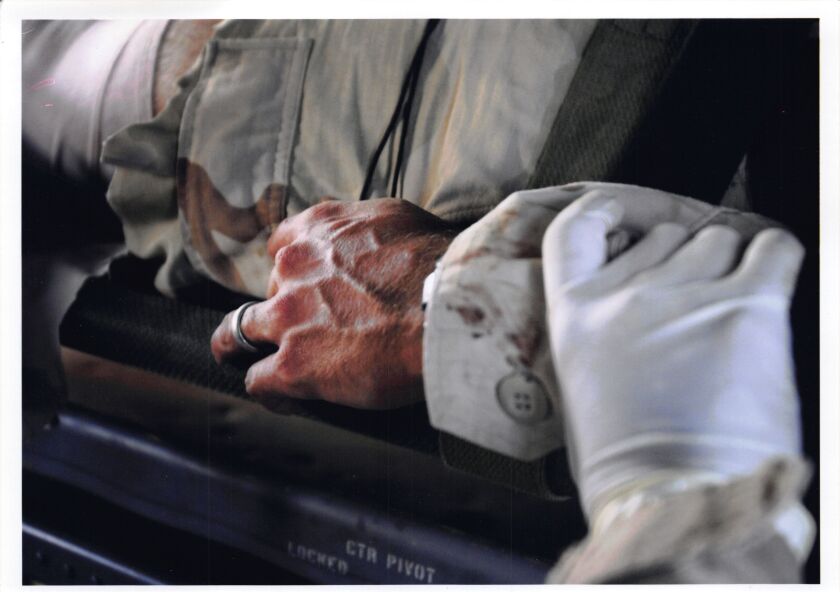

In this second stint in the military, he was on active duty on and off between 2004 and 2011, seeing combat action overseas and being wounded in a suspected suicide attack and by roadside bombs.

As a platoon leader in Afghanistan, he turned back a Taliban assault and directed medical evacuations under fire, saving other soldiers’ lives.

His unit’s deployments in 2010 to 2011 with the 101st Airborne Division were featured in the 2014 documentary film “The Hornet’s Nest.”

For his service, Rudisill, who reached the rank of captain, received honors including the Bronze Star.

Since leaving the military, he has been an FBI special agent. He has supervised cases against white supremacists and terrorist sympathizers and now is a bomb technician.

But having seen some fellow veterans turn in despair to drugs or suicide, Rudisill says he decided to again return to the Army. This time, his plan was to go back as a chaplain so he could help other service members.

Having led soldiers in combat, he says, “really makes one appreciate how delicate life is, how precious it is.”

But his plans to attend Yale fell apart when the government said he was entitled only to 10 more months of Post-9/11 GI Bill educational benefits and not the 22 he says he earned.

Without that financial support, Rudisill says he couldn’t afford Yale.

“It felt like I’d been punched in the solar plexus,” he says. “It was immediately just like the door slamming shut.”

Attorneys David J. DePippo and Timothy McHugh have represented Rudisill pro bono in challenging the VA’s decision. DePippo — whose regular job is senior counsel for Dominion Energy in Virginia — estimates that 1.7 million veterans who served in the military beginning in the late 1990s, in any branch of service, and either stayed on or returned after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks could be losing out because of the VA’s stance and the different levels of benefits the two GI Bills provide.

The federal government stands by its stance that the VA is reading the laws correctly in making its calculations.

The government’s lawyers argue it’s not the VA’s fault that Rudisill chose to switch to his Post-9/11 benefits before first using all of his lesser Montgomery GI Bill benefits. In a court filing, they say “the VA has never made any secret of the fact” that it calculates benefits this way.

The nonprofit organizations National Veterans Legal Services Program and Veterans Education Success have filed briefs in support of Rudisill. They say he and other vets should get to decide how and in what order to use their educational benefits.

Aniela Szymanski, senior director for legal affairs and military policy with Veterans Education Success, says vets should be able to use benefits from both GI Bills if their service qualifies them.

“I don’t understand, from a commonsense perspective, why one should cancel the other one out,” she says, “especially because you’ve paid into one of them.”

Having given up his spot after gaining admission to Yale, Rudisill, who has been waging this fight for five years, is now too old at 40 to be able to rejoin the Army as a chaplain. The cutoff is 38.

But he’s still hoping to finally win his case so he can complete his master’s degree in pastoral ministry from Nashotah House Theological Seminary in Wisconsin and then minister to first-responders and other vets.

“The driving force for me in this whole matter is making sure that my brother and sister veterans get what they have earned,” Rudisill says. “This is making sure that veterans, as a whole, get what was promised to them by Congress and the American people.”