Bill Pinkney, the first African American sailor to sail the world solo, died Thursday in Atlanta while filming an upcoming National Geographic documentary about the Atlantic slave trade. He was 87.

In a video posted to Facebook, Ina Pinkney — his ex-wife, with whom he remained close — said he had fallen down stairs and later died as a result of his injuries with his wife Migdalia Pinkney at his side.

Ina Pinkney said Mr. Pinkney, a Black sailor in what’s predominantly a white field in the United States, left an important legacy as a pioneer in sailing.

“Bill has a very important place in the history of Chicago,” she said in the video. “Bill was a lot of firsts, and Bill was the best at being the first.”

His life revolved around the water from early on: he was an X-ray technician in the Navy before learning to sail and a frequent visitor to Chicago’s 31st Street Beach while growing up on the South Side. He ended up racing sailboats at Belmont Harbor in the 1970s.

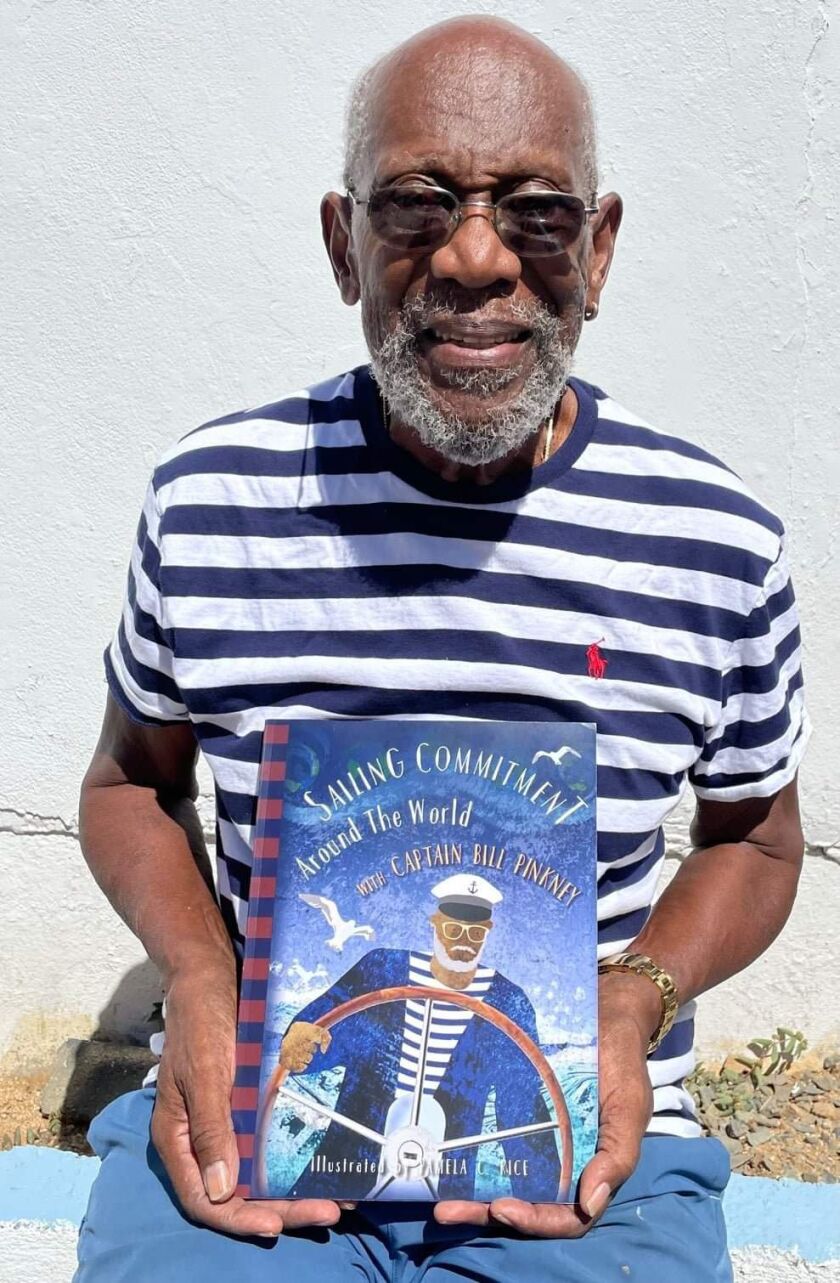

In 1992, Mr. Pinkney became the first Black sailor to sail around the world solo, taking his 47-foot yacht “The Commitment” on a 27,000-mile, 22-month trip.

During that voyage, Mr. Pinkney, then 55, taught thousands of schoolchildren lessons in science, math and geography from his boat via satellite. A video of his journey went on to win a Peabody Award.

The trip around the globe was particularly dangerous because of the route Mr. Pinkney chose, according to Jerry Thomas, a friend and the vice chairman and treasurer of the Chicago Maritime Museum. That route took him south of the capes of South America and Africa, where the winds can be dangerous, and is one that few attempt solo.

“When you take that route, you’re putting your life at risk,” Thomas said.

He said Mr. Pinkney took that route because just sailing around the world was already “out of the bounds of what some guy from the South Side should do,” and Mr. Pinkney’s competitive spirit drove him to challenge himself.

After that journey, Mr. Pinkney led voyages on the Middle Passages’ trade routes, again teaching kids, though those lessons focused mostly on the history of the Atlantic slave trade.

In 2000, Mr. Pinkney became the first captain of a replica of the Amistad, a schooner commandeered in 1839 by its captive passengers, who were residents of Sierra Leone abducted to be sold into slavery. The new crew eventually made it to the United States, where they were declared free by the courts and returned home.

It was then that he met his current wife. They fell in love — partly due to his salsa dancing skills — shortly after he refused her request for a photo at the Amistad’s launch.

“He loved dancing,” Migdalia Pinkney said. “He loved expressing himself. When we met, we danced as if we’d been dancing together our whole lives.”

Years later, Mr. Pinkney became the first Black sailor inducted into the National Sailing Hall of Fame — one of two with the honor, alongside Absalom Boston, a 19th-century whaler — and was given the Mystic Seaport Museum’s highest honor, the “America and the Sea” award, following his 14 years there as a board member.

Despite all of his accolades — which he’d joke made some think he was “greater than milk and cookies” — Migdalia Pinkney said he was driven by teaching and inspiring kids.

“No matter what he was doing, he was educating,” she said. “Bill’s main message was: All dreams come true if you make a commitment to make things possible, no matter what people tell you.”

In recent years, Mr. Pinkney continued to speak with kids taking educational trips to the Chicago Maritime Museum and the Jackson Park Yacht Club, where he swam as a child.

The museum has been preparing an exhibition on Mr. Pinkney’s trip around the world. Thomas said Mr. Pinkney had helped with that and that it could debut near year’s end, withe equipment used on the journey.

Thomas described Mr. Pinkney as “warm,” “personable” and, most important, “an inspiration.”

“We can put an exhibit together, but we’ll miss the personal connection he had with kids,” Thomas said. “Bill provided an example for kids to get rid of their boundaries.”

Mr. Pinkney didn’t want his legacy to overshadow anyone else’s, his wife said. He hoped his fame would draw attention to others doing what he was doing.

“It mattered to him that people didn’t just see him but saw all the other Black folks in Chicago who make a difference,” Migdalia Pinkney said. “Bill was just an ordinary man doing extraordinary things.”

Contributing: Neil Steinberg