The U.S. Supreme Court ruled six years ago that sentencing schemes that require life sentences with no hope of parole for crimes committed by juveniles violate the U.S. Constitution. Yet in Illinois, more than 160 prisoners are serving sentences that will likely leave them to die in prison for crimes they committed as juveniles, with virtually no hope of parole or early release under current law.

Those prisoners, identified through an Injustice Watch review of state records, remain locked up no matter how much they show remorse or produce evidence that they have been rehabilitated from the crimes they committed in their youth.

Their continued incarceration is causing a policy debate in Springfield driven by supporters of prison reform who question the costs — financially and otherwise — of keeping prisoners locked up for crimes committed as youth regardless of whether they have reformed.

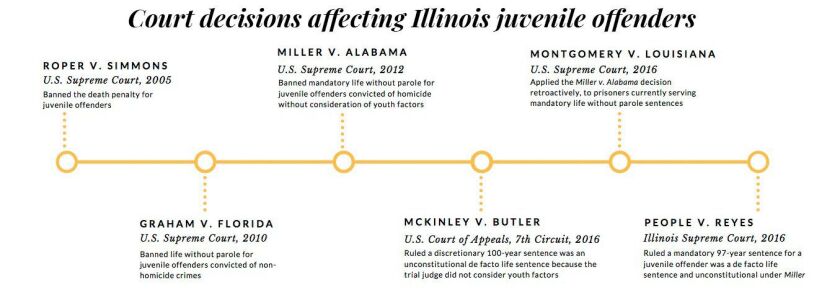

Courts and legislatures nationwide are struggling with how far to extend the logic of the Supreme Court decision that mandatory life sentences without parole amount to cruel and unusual punishment because youthful offenders’ brains are not fully developed, and therefore those defendants are both less culpable and more likely to reform as they age.

“Getting rid of formal life without parole was the tip of the iceberg,” said Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel for the Pennsylvania-based Juvenile Law Center, which has advocated for lesser sentences for juveniles convicted of crimes.

Using Illinois Department of Corrections data, Injustice Watch examined the number of prisoners serving 50 or more years in prison who were taken into custody before their 18th birthday. All but five of the 167 are serving time for murder, or murder alongside other crimes. Four are serving time for aggravated criminal sexual assault. One is serving time for armed violence.

The total of 167 is undoubtedly an undercount; the department does not record the date of the crimes, only when the suspect is held in custody.

Some 80 Illinois prisoners who were convicted of committing multiple murders as youth – crimes that carry mandatory life sentences – are among the inmates nationwide who are receiving new sentences. But those who committed less bloodshed as juveniles, including those who killed only one victim, are not guaranteed reconsideration of their sentence even if they received sentences that virtually assure they will die in prison.

Because Illinois almost entirely abolished parole in 1978, the 167 juvenile offenders do not get the same chance to show rehabilitation and change that they might get in other states. The only juvenile offenders with parole opportunities are the aging handful who were convicted before the law changed four decades ago.

There is no national legal standard on how many years is too many for a juvenile to serve. Courts across the country have differed on the issue, creating varied standards on what length of a prison term can legally be considered a life sentence, and whether and when they should be eligible for parole.

At least 13 other states and Washington, D.C., have passed laws giving young offenders a chance to ask for parole release or a sentence reduction after first serving as few as 12 and as many as 35 years in prison, depending on the state and severity of the crime.

Based on laws passed after the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miller v Alabama, these are sentences juvenile offenders convicted of serious crimes such as homicides must serve in the listed states before being eligible for parole or a sentence reduction. Some of these states still allow harsher sentences for juveniles, for the gravest offenses. | Jeanne Kuang/Injustice Watch

The Illinois Senate Criminal Law Committee last month sent to the full Senate a bill that would permit inmates who committed crimes before the age of 21 the periodic chance to ask for parole, after first serving 10 years for lesser crimes and 20 years for first-degree murder or aggravated sexual assault.

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx supports the bill, but victims’ rights advocates and suburban prosecutors have mounted opposition.

“With violent crime on the rise and a record number of shootings and carjackings in Chicago, the very idea that some of our state’s most violent murderers and rapists could be released pursuant to the Youthful Parole Bill is frightening and insulting,” states a letter on the stationery of DuPage County State’s Attorney Robert B. Berlin that is signed by Berlin and six other state’s attorneys. “Put very simply, letting violent offenders out of prison early will cost society dearly and will deny the People of Illinois the full measure of justice they are entitled to.”

Illinois victims’ rights advocate Jennifer Bishop-Jenkins contends repeated parole hearings are akin to “torturing the victim” by forcing repeated reminders of traumatizing memories of their loved ones’ death.

Bishop-Jenkins said she supports greater consideration of a defendant’s age and mental health at sentencing, but she said she believes one “mid-sentence review” is enough.

Illinois juvenile prison population

InfogramResearch indicates that incarceration has a jarring effect on life expectancy; a study by Vanderbilt University Professor Evelyn Patterson found each year of incarceration likely reduces a prisoner’s life expectancy by two years.

The United States Sentencing Commission considers a 39-year prison sentence the equivalent of life.

Courts across the country are struggling with cases brought by prisoners who contend sentences for their teenage crimes should be revisited because they are excessively long.

In Iowa, for example, the State Supreme Court in 2013 threw out a sentence that made a juvenile offender parole-eligible only after serving 52 and a half years, because it afforded him only “the prospect of geriatric release” without a meaningful opportunity to demonstrate rehabilitation. Citing that decision, the Wyoming Supreme Court in 2014 ruled the same way on a sentence that required a juvenile offender to serve 45 years before having a chance at parole.

“The challenge that all these courts are facing is literally where to draw the line and how to pick a number,” Levick said.

The Illinois Supreme Court in 2016 overturned Zachary Reyes’s automatic aggregate 97-year prison term as a functional life sentence. Citing that decision, a state appeals court last year threw out 16-year-old offender Dimitri Buffer’s 50-year sentence. But a different appellate court last year said the Illinois Supreme Court decision did not apply to Rafael Santos and upheld his discretionary 70-year sentence.

Injustice Watch interviewed 11 Illinois inmates serving prison sentences of 50 years or longer for crimes they committed before they were 18. One after another, they described their experiences growing up marred by poverty and violence, and their sense that, despite the growth and progress they said they have made entering adulthood in prison, society has already thrown them away.

Among them was Benard McKinley, who was outside a Chicago park in 2001 when Abdo Serna-Ibarra, 23, arrived there for a soccer game.

Words were exchanged, and a 15-year-old on a bicycle called out: “Shoot him, shoot him.” McKinley, 16, obliged. He was charged as an adult with murder and convicted in 2004.

Cook County Circuit Judge Kenneth J. Wadas said he was sending a message to deter other criminals and enable others to play soccer with “one less Benard McKinley out there with a handgun blowing them away.” Wadas sentenced McKinley to 100 years in prison – 50 years for the murder, and a consecutive 50 years for the fatal use of a firearm.

Because Wadas could have sentenced McKinley to as little as 45 years, the prisoner was not assured resentencing.

But McKinley turned to the federal courts nevertheless, and his attorneys argued that during sentencing the judge had barely acknowledged his young age and ignored the rehabilitative strides McKinley made in jail.

By a 2-1 vote in 2016, McKinley became one of the rare lucky ones. Writing for the majority, now-retired U.S. Circuit Judge Richard A. Posner wrote that Wadas had “treated McKinley as if he were not 16 but 26 and as such obviously deserving of effectively a life sentence.”

Exoneration Project attorney Karl Leonard, one of McKinley’s lawyers, said the legal team is now gathering mitigating evidence and preparing to bring in an expert witness in hopes of getting McKinley a lower sentence.

He said he does not know if clients like his would benefit from a parole opportunity but added: “I think the better solution is just to not be sending children away to prison for the rest of their lives.”

Emily Hoerner and Jeanne Kuang are reporters for Injustice Watch, a non-partisan, not-for-profit, multimedia journalism organization that conducts in-depth research exposing institutional failures that obstruct justice and equality.