Janice Jackson, the Chicago Public Schools’ new boss, wants her 371,000 students and their families to know she’s one of them.

Jackson, 40, spent all of her school days in CPS classrooms — from Head Start at Cook Elementary through Hyde Park High School.

She returned after college as a social studies teacher. Rising through the ranks all the way to chief executive officer, she has never left.

The Chicago schools are also where she sends her own kids, making her the first CPS graduate and mom to oversee the nation’s third-largest school district.

“No role in CPS better prepares me than being a CPS parent,” she said at her first Chicago Board of Education meeting in charge. “Know that, in the CEO, you have somebody who has experienced the district and owes all of my success to CPS — but I look at it through the lens of a parent.”

There’s also another way Jackson can relate to many of the kids in her care and the families who entrust them to her, one she usually prefers not to talk about. A clue to that appears in the 200-page dissertation she wrote in 2010 to earn her doctorate from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

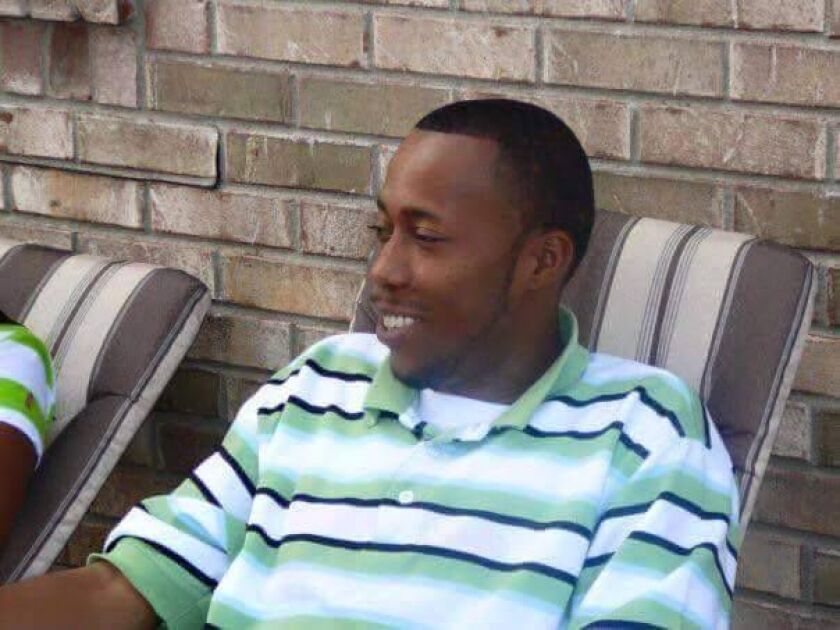

“This work is dedicated in loving memory of my baby brother, Cordney L. Jackson,” she says on its opening page. “Cordney — I love and miss you.”

Cordney Jackson died earlier that year. He was shot three times in their mother’s home while trying to protect her and her friends from two masked robbers who burst in while the women were playing cards.

“Don’t hurt my mamma,” he yelled.

Shot in the chest, back and an arm, Cordney Jackson, who drove a cab, fell down the basement stairs and died. He was 31 years old.

After seven years, the police have made no arrests.

When her brother was killed, Janice Jackson was 32 and had a 1-year-old daughter. It was her first year as principal of the new Westinghouse College Prep High School on the West Side. She was balancing the demands of her job and her baby girl with working on her doctorate.

Asked about her brother, Jackson said his death was “a senseless act of violence” at the hands of teenagers. She also said his memory pushes her to work to expand opportunities for all young people but especially African-American boys.

Jackson doesn’t often talk about what happened to her brother.

“It’s the experience that so many people have, and it’s unfortunate,” she said in an interview. “And I don’t want to make it about me. I think it once again is another thing that gives me the perspective that’s needed to know that the stakes are real, that education is a way for people to really put themselves on a path where they can change their lives — and that’s not just the people who are the victims to the violence that we see in the city but also the perpetrators of violence.

“So when I’m out here trying to improve schools, improve opportunities, I’m thinking just as much of the people who can be impacted by violence as the people who can be perpetrators of violence. And it sounds optimistic, but I believe, if people have a chance, if they have hope, if they believe they can have a good life, I think that they’ll make different choices. And we need more of our kids to feel that way.”

Another reason for holding back: “My mom does not like me to talk about it. It was extremely hard for her, extremely hard because this is a kid who did everything right. Doesn’t have a background, wasn’t involved in anything bad. He’s a great kid.

“And, because of senseless violence, mainly from young kids — we don’t know who did it, it’s an unsolved crime — but they were teenagers who were just making bad decisions.”

Janice Jackson grew up on the city’s South Side in Auburn-Gresham, the third of five children in her family, 19 months older than the brother she lost. Her father was a cab driver, her mother a taxi dispatcher.

By 2000, she had bought a brick house for her parents in West Pullman on the Far South Side.

Every Friday night, going back three decades, Jackson’s mother told police, she was part of a group of about a dozen women who’d get together to play cards.

They’d rotate houses. The evening of March 26, 2010, it was Jackson’s mother’s turn to host, according to heavily redacted Chicago Police Department records that provide a rough narrative of what happened the night Cordney Jackson got shot.

In the home’s finished basement, each of the women handed over her $100 buy-in, and they started playing.

There was food set out on tables. And, between hands, the women chatted on seats along a wall. It was only women, always had been. No men were allowed.

Cordney Jackson — who was upstairs in a bedroom with someone watching TV — knew that. So when he heard men’s voices around 12:30 a.m., he told his companion to call 911, grabbed a baseball bat and, dressed in only his boxers and socks, headed toward the door from the kitchen to the basement.

Two young men, dressed all in black with ski masks over their faces and armed with handguns, had slipped into the basement from a rear door and shouted, “This is real, ladies.”

One waited at the bottom of the stairs. The other approached the table where the women were playing Tonk, grabbed their cash and several of their purses. Some of the women tried to hide under the table. One told the police she closed her eyes and prayed.

Handbags in hand, the men ran up the stairs, where Cordney Jackson was waiting.

The women heard shots and a struggle, then Jackson’s voice as he came down the stairs with bat in hand, then more shots. The robbers ran out the back door, dropping some of the purses.

Some of the women told the police they suspected the robbers had been tipped off about the game.

“My brother left behind a son who motivates me,” Janice Jackson said. “He’s a young, African-American boy who is extremely smart. Making sure he’s on the right path and making sure he gets all the opportunities — those are the things that drive me.”