Rabbi Robert J. Marx’s description of the racial hatred he witnessed at a Southwest Side open housing march more than half a century ago still has the power to shock:

“What I saw in Gage Park seared my soul. . . I saw how the concentration camp could have occurred, and how men’s hatred could lead them to kill. I saw Catholic priests reviled and nuns spat upon. I found myself — a rabbi — standing guard like a policeman, over a pile of rocks, for fear that grown men and mothers dragging little children around with them would seize those rocks and throw them at the demonstrators. I saw teenage boys and girls ready to kill.”

The Chicago Commission on Human Relations asked Rabbi Marx to monitor the gathering. But after seeing the vitriol directed at Black demonstrators by angry white crowds, he said he decided this:

“I should have been with the marchers.”

When the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. organized a follow-up demonstration on Aug. 5, 1966, Rabbi Marx wrote an open letter to members of Chicago’s Reform Jewish community, saying he planned to join King’s group in the Gage Park-Marquette Park area.

After being struck that day by a rock thrown at him, King famously said, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say that I have never seen — even in Mississippi and Alabama — mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen in Chicago.”

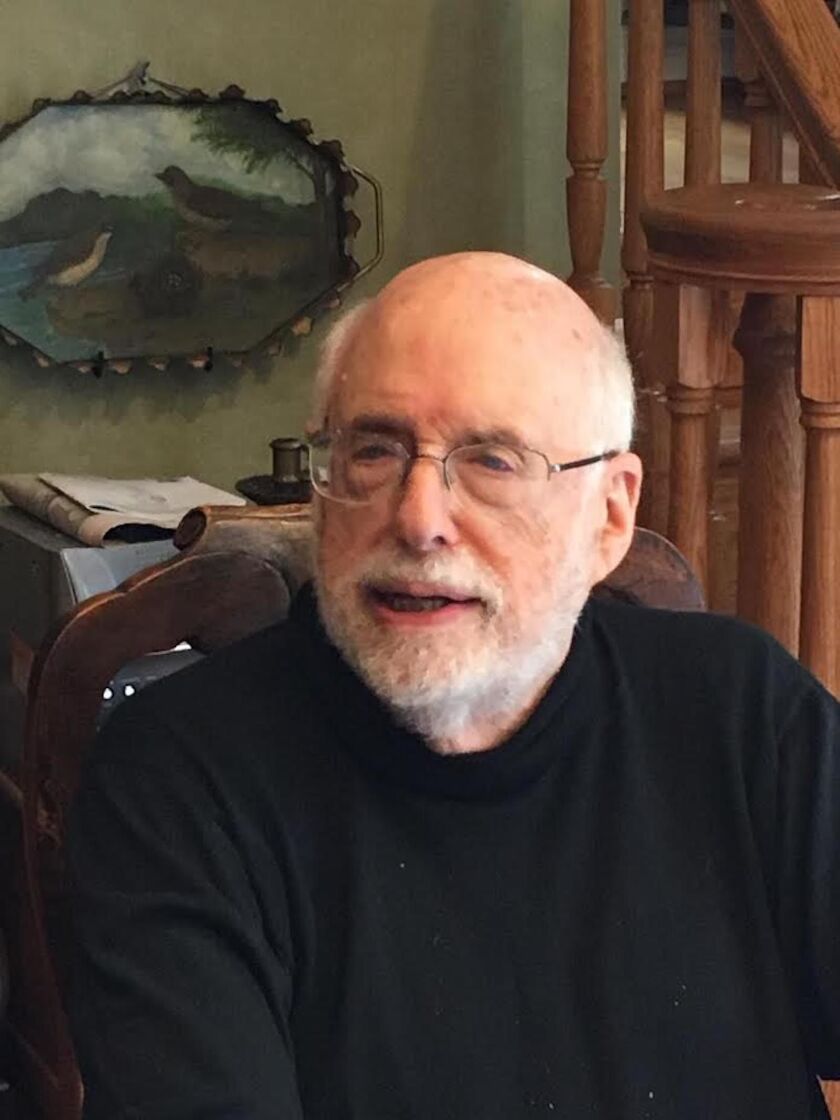

Rabbi Marx, who also was pelted with rocks at that protest, died March 28 at 93.

Interviewed for an oral history, the rabbi said he felt he had to get involved:

“I got up, my son and I, holding hands, and we walked into the middle of the street and started marching with Dr. King. Something happened at that moment that said, ‘You can’t be an observer. You’ve got to be a participant. You’ve got to go across the street’ — and that’s what I did.”

A national leader in Reform Judaism and one of Chicago’s staunchest civil rights activists, he became a trusted ally of Black leaders and interfaith activists who fought for equality in jobs and housing and justice for immigrants and the homeless.

He believed that, “where there is racism, there’s anti-Semitism,” said Jane Ramsey, former director of Chicago’s Jewish Council on Urban Affairs.

In 1963, the rabbi attended the March on Washington. Decades later, he recalled helping an elderly Black man who fell during the march. The man told him: “I’ve lived in this country 76 years. But only today I became an American.”

Rabbi Marx founded the Jewish Council in 1964 with $15,000 from a Merrill Lynch foundation — a donation that came thanks to prodding from famed community organizer Saul Alinsky, according to Ramsey. The organization supported social justice issues with civil rights figures including King, Al Raby, Chicago Reporter founder John McDermott, Monsignor Jack Egan and the Rev. Edgar H.S. Chandler.

In 1965, he marched with King in Selma, Alabama.

The following year, Rabbi Marx, again joining King, spoke at Soldier Field, declaring, “We who have seen the slaughter of six million of our brothers can only shudder in cognizant agony at the thought that our Negro brothers are still dying to purchase the same freedom for which we too have bled and died.”

“Every march, he was there,” the Rev. Jesse Jackson said. “He was a bridge in Chicago. He was a bridge between blacks and Jews and Israelis and Palestinians. He never stopped building bridges.”

Roger Ebert, the late Chicago Sun-Times film critic, noted Rabbi Marx’s work with the Contract Buyers League — which organized rent strikes and picketing to fight redlining and block-busting on the West Side — when he reviewed the documentary “Blacks and Jews” at the 1997 Sundance Film Festival.

In a 2016 speech at the National Prayer Breakfast, President Barack Obama cited Rabbi Marx for his civil rights work.

The rabbi’s likeness decorates the MLK Living Memorial at Marquette Park, which has a panel inscribed with his letter about his shock at the racial hatred he once witnessed.

The memorial was organized by the Inner-City Muslim Action Network, whose executive director Rami Nashashibi said: “Part of his devotion to his faith and his love for his community was in ensuring that that community lived up to its highest ideals of justice and equality. And that was evident in Rabbi Marx’s life’s work and in the powerful organization he founded.”

He grew up in Cleveland. As a freshman reporter for the student newspaper at what was then Western Reserve University, he covered a news conference held by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a polio survivor.

“I was such an observant reporter,” the student writer wryly observed, “that I had no idea then or until much later that the President was unable to walk, that all those people surrounding him, were actually holding him up as he entered and left the room.”

Rabbi Marx was ordained at Cincinnati’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and got his doctorate in philosophy at Yale University.

He went on to be director of the Midwest region of the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, now the Union for Reform Judaism, the largest of the country’s Jewish denominations.

From 1973 to 1983, he was rabbi of Congregation Solel in Highland Park, where he helped lead a support group for parents who’d lost a child. His 15-year-old son David died in 1973 after a long illness. Rabbi Marx co-wrote a book for grieving parents, “Facing the Ultimate Loss.”

He also wrote the book “The People in Between: the Paradox of Jewish Interstitiality.”

In 1983, he founded Congregation Hakafa in Glencoe.

“Robert never attacked the person. He always addressed the issue,” said Rabbi Bruce Elder of Congregation Hakafa.

Rabbi Marx, who had a heart attack about two weeks ago, died at his home in Saugatuck, Michigan, Elder said.

A public memorial is planned at 1 p.m. June 27 at Beth Shalom B’nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation, 6601 S Kedzie Ave. Space is limited, so attendees are asked to register in advance. The gathering also can be viewed online, Elder said.

Rabbi Marx’s survivors include his son Richard “R.J.” Marx from his first marriage to the former Marjorie Plaut, his second wife Ruth, stepchildren Suzi Geguzys Schoonmaker, Sandi Geguzys Stanfel, Ron Geguzys, Vicki Geguzys Fredman and Cynthia Geguzys Schuman and 17 grandchildren.

In his 1966 letter to the Reform Jewish community, the rabbi said he sometimes was asked, “Why don’t I spend more time on Judaism? Why do I dissipate so much of my energy on a cause that is not ours?.

“I feel that freedom is Judaism, that Passover is not 3,000 years old — that it is today, and that we are part of it.”